A growing wave of ‘knowledge games’ is rejecting reflex tests and platforming puzzles in favor of something more radical: trusting players to think. By reframing these works as “database thrillers,” designers are quietly building one of the most accessible—and technically intriguing—genres in modern interactive storytelling.

Beyond Mechanics: The Rise of Database Thrillers as a True Knowledge-First Genre

There is a small but rapidly cohering corner of game design that treats curiosity as its primary input device. No combo chains. No pixel-perfect jumps. No crafting grinds. Just: you saw something, you thought about it, now what do you want to look up next?

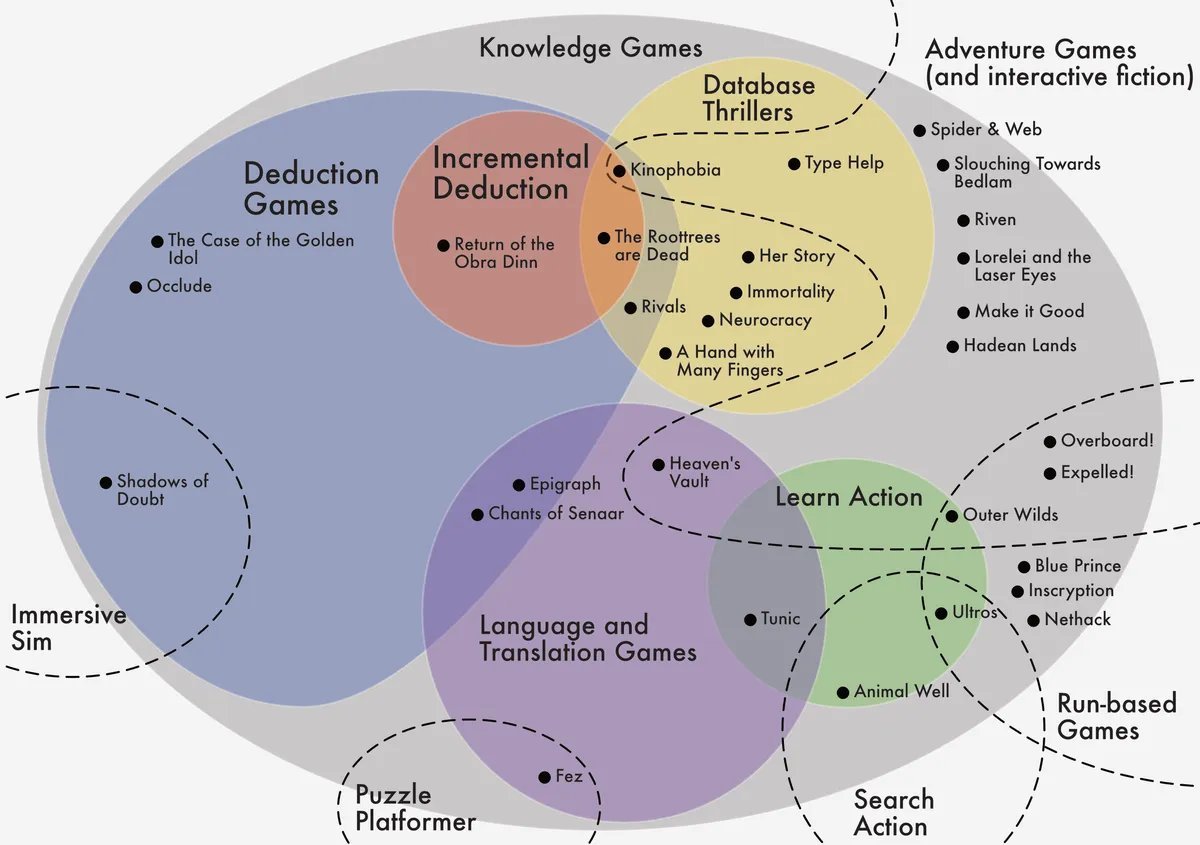

Across blogs, talks, and the more self-aware corners of game dev social media, this design space has been circling a cursed joke-term: “metroidbrainia.” It’s cute, it’s sticky, and—as Victoria Buckenham and Bruno Dias both argue—it’s also deeply misleading.

Their counterproposal isn’t just semantic hygiene. It’s a clearer lens on a genre with serious implications for narrative design, tooling, accessibility, and how we think about systems like search, retrieval, and inference inside interactive experiences.

Buckingham’s recent piece, published on her blog and in dialogue with Dias’s Against ‘Metroidbrania’: a Landscape of Knowledge Games, makes the case for a sharper concept: the database thriller.

Definition (per Buckenham): “A database thriller is a game where progression is gated only by understanding of a particular narrative.”

For developers, that framing is not a tagline. It’s an architectural constraint.

The Ancestry: Sherlock Holmes, Not Super Metroid

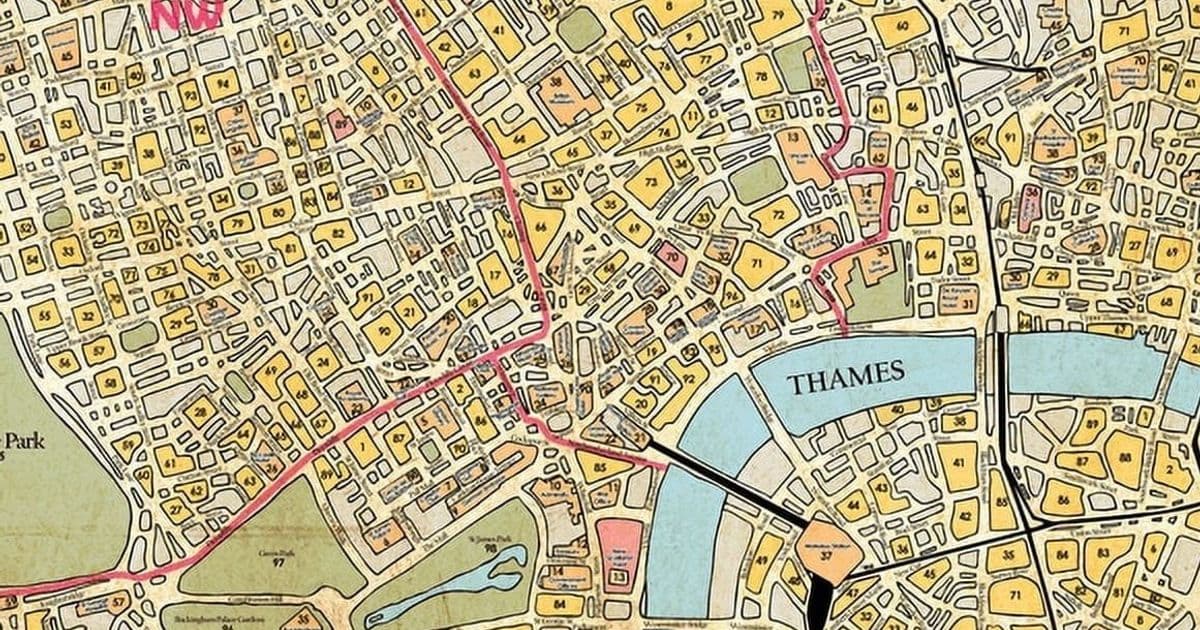

The crucial pivot is conceptual: instead of reaching for Metroidvanias and their ability-gated maps, Buckenham points to a board game from 1982—Sherlock Holmes: Consulting Detective—as ground zero.

In Consulting Detective, players get:

- A city map

- A directory of people and locations

- A newspaper

- A case booklet keyed to those locations

From there, it’s pure information work. You decide where to go, what to read, who to visit. The game doesn’t hide the city behind arbitrary locks; it hides the solution behind your ability to form and test hypotheses.

The mechanics are almost offensively simple:

- Notice a detail (a tobacconist, a birth date, a social link)

- Ask a question (where would that person be listed? what record would reflect that?)

- Jump into the database (map, directory, booklet, newspaper)

- See if your story still holds up

There’s no twitch skill ceiling, no emergent physics, no combo-routing. The friction is cognitive, not motor. This is the exact dynamic that will later power Sam Barlow’s Her Story, where you interrogate a fragmented archive of police interview clips entirely via free-text search.

In both cases, your theory of the narrative world is the only real progression system.

This is precisely why “metroidbrainia” obscures more than it reveals. The Metroidvania metaphor drags in expectations about:

- Ability-gated traversal

- Spatial mastery as progress

- Systemic or movement-based upgrades

Database thrillers, by contrast, are not about unlocking places or verbs; they’re about unlocking explanations.

Design Constraint as Genre: “Gated Only by Understanding”

Buckhenham’s definition hides a demanding spec for anyone building one of these games.

1. It must be a game

There has to be a playable goal state: solve the case, uncover the conspiracy, identify the culprit, reconstruct the timeline. This isn’t just a wiki with vibes; the structure of play matters.

2. Progression is only about comprehension

This is the hard line.

If your player must:

- Execute a precise platforming sequence

- Grind a stat

- Master a complex timing mechanic

- Reverse-engineer opaque simulation systems

…then knowledge is no longer the only gate. You may be making an excellent game, but you’ve left database thriller territory.

What remains admissible is explicit reasoning about information: choosing what to look up, cross-referencing entities, testing story hypotheses against an accessible corpus.

3. The knowledge is narrative, not merely systemic

This is where some well-meaning replies—“Isn’t Hitman an information game?” “What about Stacklands?”—get a firm but fair no.

Those games are about learning systems, affordances, and possibility spaces—valuable, rich, and absolutely about knowledge. But the core arc is not: what really happened? who did what, when, and why? It’s: how can I bend these mechanics to my will?

Database thrillers, as framed here, are about a particular story:

- Who lied?

- Which records conflict?

- What timeline fits all observations?

The gating knowledge is semantic and narrative, not just ludic.

Why This Matters for Developers (Beyond Terminology Fights)

Underneath the genre taxonomy is a set of design and engineering challenges that should interest anyone building narrative systems, search experiences, or AI-enhanced tooling.

1. Search UX as Core Game Loop

Her Story’s genius is not only its writing; it’s the daring bet that search is sufficiently expressive and satisfying to be the main verb.

For developers, this is an open playground:

- What counts as a “query”? Free text, tags, map locations, documents, social graphs?

- How transparent is the corpus? Are all nodes visible, or is discoverability part of the puzzle?

- How do you prevent trivial brute force (e.g., alphabetically trying terms) without adding arbitrary gates?

Designing a database thriller forces you to treat your indexing, retrieval, and presentation layers as game systems, not just content plumbing.

2. Tooling for Narrative Consistency at Scale

If progress is gated by understanding, then contradictions, dangling threads, and ambiguous phrasing aren’t just polish issues—they’re potential soft-locks.

This pushes teams towards:

- Stronger internal knowledge graphs (characters, entities, timelines)

- Validation tools for narrative continuity

- Structured writing workflows where every clue is intentionally placed and cross-referenced

The genre effectively demands story-aware tooling that many narrative pipelines still lack.

3. Accessibility Without Dilution

One of Buckenham’s most important observations: this genre is genuinely accessible to people with little or no traditional videogame experience.

There is no prerequisite literacy in:

- twin-stick movement

- stamina meters

- hitboxes

- character builds

Instead, the required skills are:

- reading comprehension

- pattern recognition

- hypothesis testing

For studios and indies looking to reach new audiences—or to justify narrative-heavy projects that don’t lean on inherited action mechanics—database thrillers are a powerful model.

And this is precisely why names like “metroidbrainia” are self-sabotaging: they encode prior hardcore literacy into the label of a genre that thrives on meeting players where they already are.

The Edge of the Definition: Escape Rooms, Spaces, and Hybrids

Buckhenham is explicit: this isn’t purist gatekeeping. Definitions are useful because they invite transgression.

Key tensions worth exploring as a developer:

- Spatiality: Can a database thriller meaningfully live in 3D space? If walking across a room is trivial but choosing which filing cabinet to open is the core decision, you’re likely still within the frame.

- Physical play: Could an escape room qualify? Only if its locks yield purely to narrative comprehension, not dexterity or arbitrary code-breaking for its own sake.

- Hybrid forms: Many of the most exciting designs will flirt with the boundary—adding light mechanical friction without undermining the primacy of narrative understanding.

The point is not to police borders, but to protect the clarity of a design challenge: What happens if we let understanding be the only gate? What new forms, UIs, and narrative architectures appear?

A Broader Lineage of Information Games

Buckenham nods to Bruno Dias and Tom Francis, both of whom have spent years mapping the wider territory of information games:

- Dias explores taxonomies of knowledge-driven designs beyond crime stories

- Francis’s talks dissect how games can turn information discovery and deduction into satisfying loops

Database thrillers sit inside this larger ecosystem as a sharply defined sub-genre. Not every game that teaches you something is an information game in this sense; as Raph Koster has argued, all games involve learning. What distinguishes this cluster is that information itself is the manipulable resource and correct interpretation is the win condition.

This clarity is a gift to practitioners. It gives developers a way to:

- Pitch projects without handwaving: “This is a database thriller—progress is gated only by narrative understanding.”

- Design tests for their own prototypes: “Can a smart, non-gamer with good reading skills finish this without learning any bespoke mechanics?”

- Reason about scope: every new clue or document is not just content, but a node in a logical structure players must be able to traverse.

Where Curiosity Becomes Interface

Buckenham’s argument lands on an understated but potent idea: when you strip away mechanical gatekeeping, what’s left is a kind of radical trust.

You trust your players to:

- Notice

- Infer

- Remember

- Reconsider

You trust your systems to respond legibly to that curiosity.

For a medium that has spent decades equating “depth” with skill trees and execution complexity, database thrillers are a quiet rebellion—deep, but only in the dimension that stories actually inhabit.

For developers, they’re also a design lab for problems that reach beyond games: transparent retrieval systems, explainable inferences, human-centered interfaces to dense knowledge graphs.

And once you see that, the name almost doesn’t matter. But if this space is going to keep growing—and it should—it deserves terminology that illuminates its strengths instead of smuggling in someone else’s.

Call them database thrillers. Then build systems worthy of the term.

Source: Analysis based on Victoria Buckenham’s blog post “Database thrillers, or: against metroidbrainia” (blog.vbuckenham.com) and its dialogue with Bruno Dias’ “Against ‘Metroidbrania’: a Landscape of Knowledge Games,” alongside referenced work by Tom Francis.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion