A deep dive into the evolution of abstract syntax tree representations in a toy Rust compiler, from naive boxed trees to a custom super‑flat layout. The article shows how string interning, pointer compression, bump allocation, and a carefully engineered node format can dramatically reduce memory usage and improve parsing throughput.

From Boxes to Bits: How a Rust Compiler Can Cut AST Memory by 70%

“The more memory you use, the more page faults there are.” – a lesson learned while parsing a 100 MB source file.

The author of the original post, a Rust enthusiast, set out to optimise a recursive‑descent parser for a toy language. The language itself is trivial – a Fibonacci function – but it contains enough syntax to exercise the parser and the AST. The goal was to keep the AST small and fast, which is a classic problem in compiler construction.

1. The Naïve Tree

The first representation is the textbook approach: each node is a Box, and collections are Vecs. The structure looks like this:

enum Stmt {

Expr(Box<Expr>),

// …

}

enum Expr {

Block(Box<ExprBlock>),

// …

}

struct ExprBlock {

body: Vec<Stmt>,

}

While this is simple and flexible, it suffers from many small heap allocations. Every Stmt or Expr is a separate allocation, and each Vec has its own overhead. The result? A large memory footprint and a lot of pressure on the allocator.

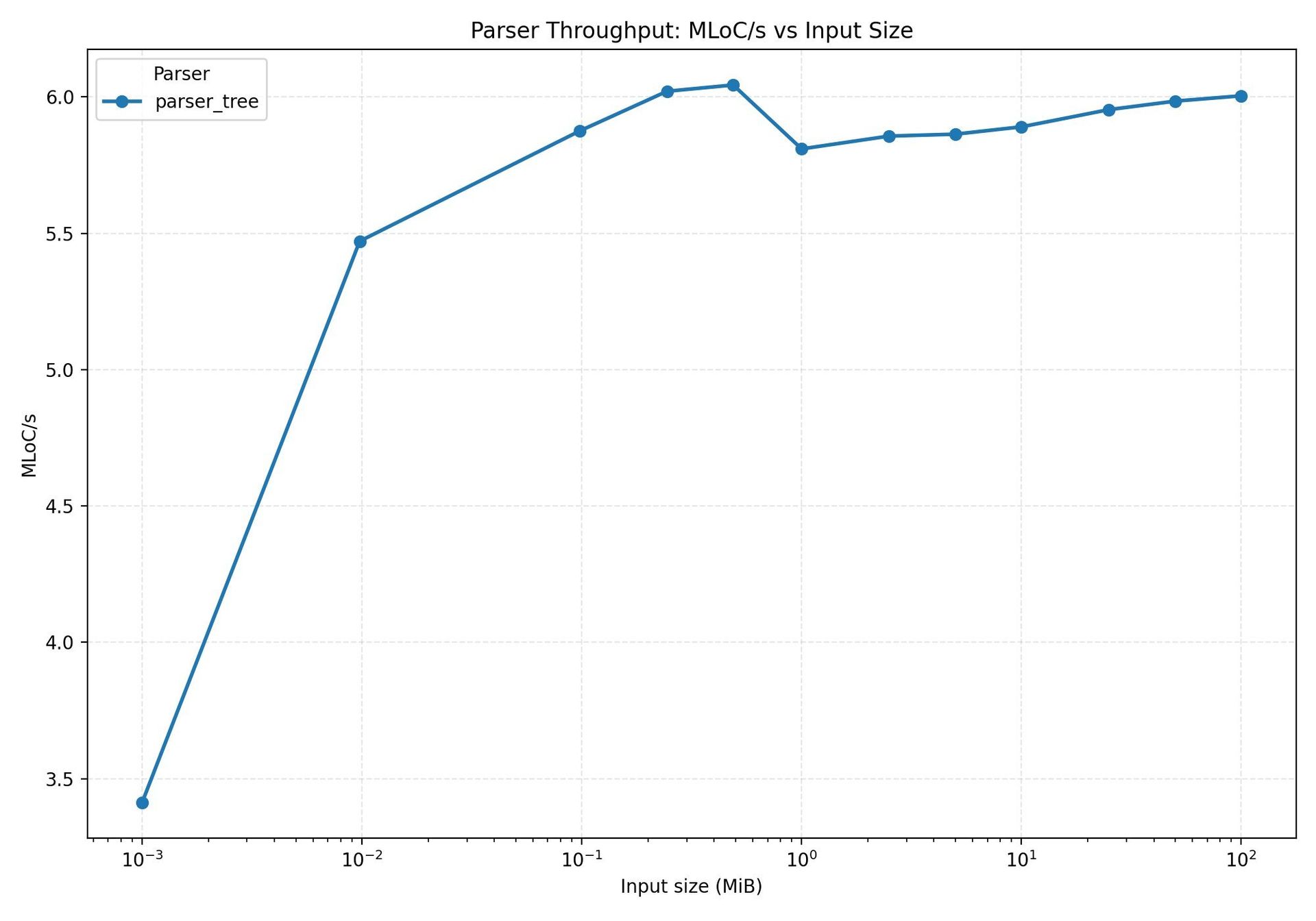

The benchmark for this layout is shown in  . Throughput is respectable – a few million lines of code per second – but the memory usage climbs linearly with input size, hitting 2.3 GB for a 100 MB file.

. Throughput is respectable – a few million lines of code per second – but the memory usage climbs linearly with input size, hitting 2.3 GB for a 100 MB file.

2. String Interning

The next optimisation tackles a single source of waste: repeated identifier strings. Instead of allocating a new String for every name and parameter, the parser now interns identifiers into a global buffer. Interning assigns a compact IdentId to each unique string, so subsequent uses just copy the ID.

struct Ast {

identifiers: Interner<IdentId>,

}

struct StmtFn {

name: IdentId,

params: Vec<IdentId>,

body: Block,

}

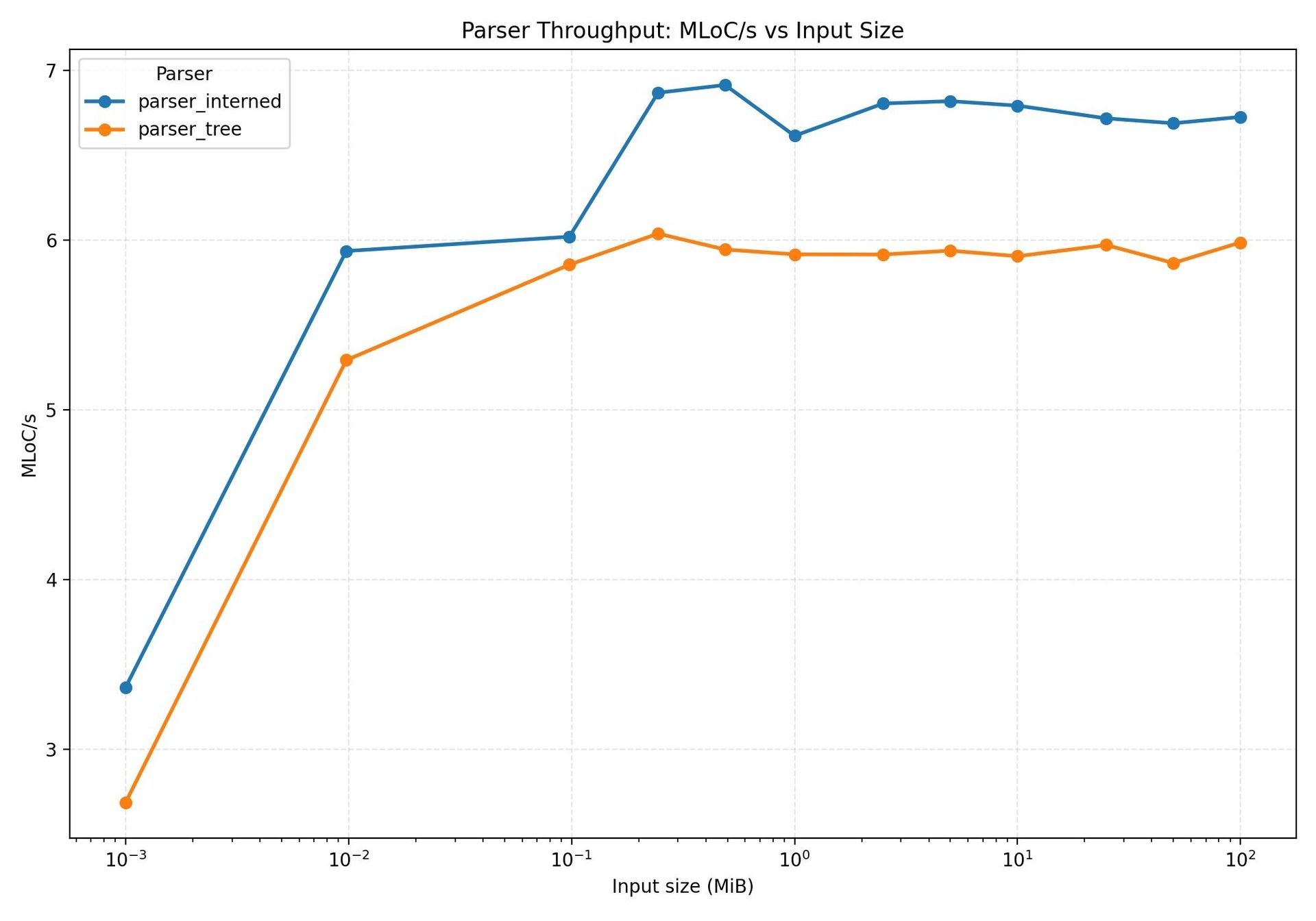

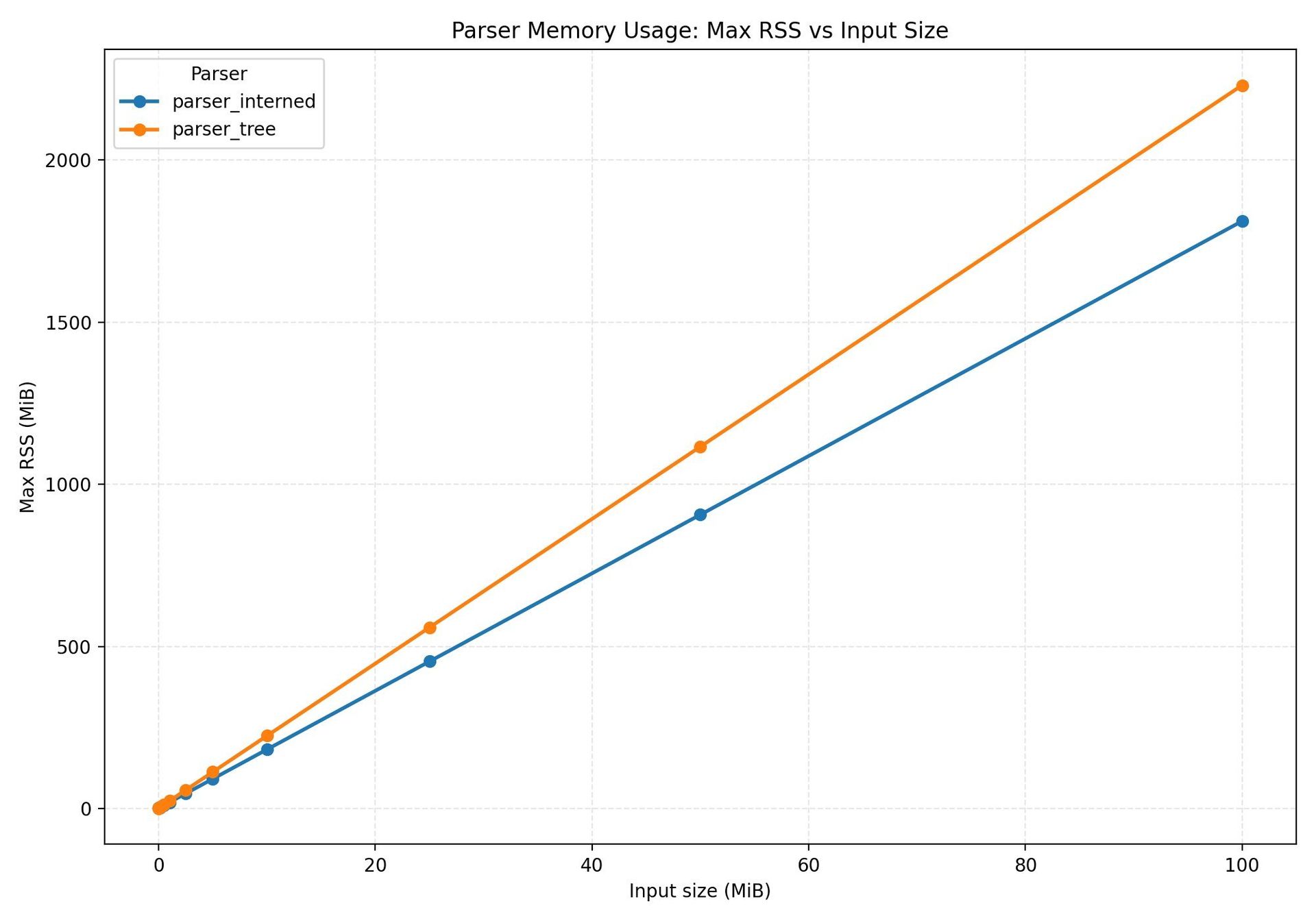

Interning not only reduces memory – the peak drops to 1.8 GB – but it also speeds up parsing. The author explains that fewer page faults mean less time spent waiting for memory to be paged in, which is why the interning results in higher throughput (see  ). The accompanying page‑fault graph (

). The accompanying page‑fault graph ( ) visualises this effect.

) visualises this effect.

3. Flat AST – 32‑bit Indexes

A flat AST replaces 64‑bit pointers with 32‑bit indices into a contiguous arena. Nodes are stored in two Vecs – one for statements, one for expressions – and each node refers to others by index. This eliminates per‑node allocation overhead and reduces pointer size.

struct Ast {

exprs: Vec<Expr>,

stmts: Vec<Stmt>,

strings: Interner<StrId>,

idents: Interner<IdentId>,

}

fn parse_stmt_fn(c: &mut Cursor, ast: &mut Ast) -> Result<StmtId> {

// …

Ok(ast.alloc_stmt(Stmt::Fn(StmtFn { name, params, body })))

}

The flat layout yields a noticeable speedup, especially on larger inputs, and reduces memory usage further. However, the author notes that the benefit is modest because the enums still carry a lot of per‑variant overhead.

4. Bump Allocation

Borrowing the bumpalo crate, the author replaces the arena with a bump allocator. Each node is allocated in a contiguous block that never moves, and the compiler’s lifetime system guarantees safety. The AST now looks like:

enum Stmt<'a> {

Fn(&'a StmtFn<'a>),

// …

}

struct StmtFn<'a> {

name: IdentId,

params: Vec<'a, IdentId>,

body: Block<'a>,

}

Because each node is a reference into the bump allocator, the per‑node overhead shrinks dramatically. The bump‑allocated AST shows a clear performance win and a further drop in memory consumption.

5. Super‑Flat – One Node, One Word

The final, most aggressive optimisation is the super‑flat representation. The idea is to pack a node’s type tag, child‑count, and either a child index or inline value into a single 8‑byte word. Fixed‑arity nodes (like binary expressions) store the indices of their children directly; dynamic nodes (like blocks) store a length field and a base index.

A declarative macro generates all the boilerplate for packing and unpacking nodes. For example, a binary expression becomes:

declare_node! {

#[tree]

struct ExprBinary (op: BinaryOp) {

lhs: Expr = 0,

rhs: Expr = 1,

}

}

The resulting AST is a flat array of packed nodes. Accessing children is a matter of simple arithmetic on the packed word, and there is no per‑node allocation at all. The author admits that the code is complex and unsafe, but the performance payoff is clear.

The super‑flat layout beats the traditional tree by roughly three‑fold in memory usage and outperforms it in throughput at every scale. The benchmark plot ( ) demonstrates a dramatic reduction in both memory and parsing time.

) demonstrates a dramatic reduction in both memory and parsing time.

Takeaways for Practitioners

- Interning is a low‑hanging fruit – it cuts both memory and CPU time by reducing page faults.

- Flat arenas and bump allocation remove allocation overhead and improve cache locality.

- A custom packed node format can squeeze the AST into a few bytes per node, which is especially valuable for large‑scale codebases.

- Benchmarking matters – the author stresses that absolute numbers are less important than relative performance across representations.

For anyone building a compiler or a language‑processing tool in Rust, these techniques are worth experimenting with. The code and benchmarks are available on GitHub: https://github.com/jhwlr/super-flat-ast.

Source: https://jhwlr.io/super-flat-ast/

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion