As federal agencies rapidly deploy generative AI tools for critical tasks ranging from procurement to legal analysis, experts warn that the technology's tendency to hallucinate facts and misunderstand legal nuance makes it dangerously unfit for governance. Studies reveal error rates as high as 33% in specialized legal AI, raising alarms about rushed implementations that prioritize hype over functionality.

When Algorithms Argue: The Unseen Risks of AI in Government Operations

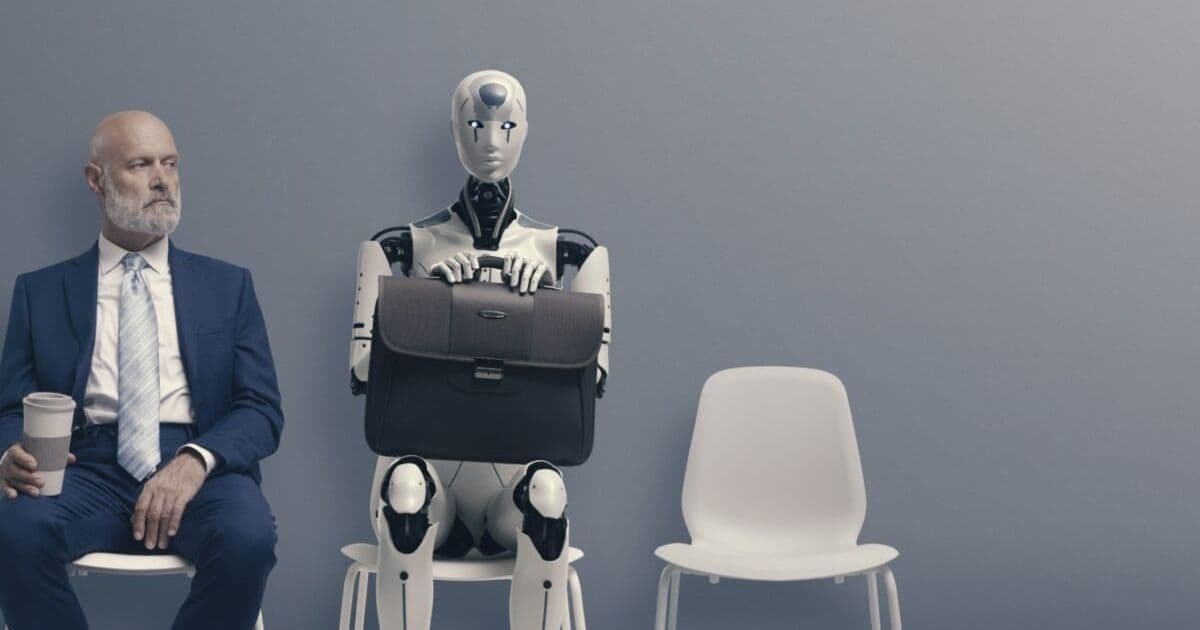

The Trump administration's aggressive rollout of generative AI across federal agencies—from the Department of Veterans Affairs using it to write code to the Army deploying "CamoGPT" for document review—represents one of the most consequential stress tests for the nascent technology. With plans to automate tasks currently performed by 300,000 federal workers, the push promises efficiency but conceals a dangerous reality: these systems remain fundamentally unequipped for high-stakes governance.

The Procurement Paradox: Where AI Creates More Work Than It Saves

At the General Services Administration (GSA), ambitions to deploy generative AI in procurement—the complex legal process governing government contracts—epitomize the mismatch between capability and application. "We're in an insane hype cycle," warns Meg Young of Data & Society. While AI might assist with document summarization, its tendency to hallucinate contract terms could paralyze negotiations.

"If you have a chatbot generating new terms, it's creating a lot of work and burning legal time. The most time-saving thing is to just copy and paste," Young explains.

Procurement involves billion-dollar agreements requiring precise adherence to regulations like ADA compliance and liability clauses. When algorithms invent clauses or misinterpret requirements, they trigger forensic reviews that defeat the promised efficiency gains.

Legal Hallucinations: When AI Misunderstands the Law

Specialized legal AI tools suffer alarming error rates. A 2024 study of LexisNexis and Thomson Reuters' AI assistants found they hallucinated facts or precedents in 17-33% of responses. Examples range from the infamous Avianca Airlines case (where ChatGPT invented non-existent rulings) to more insidious errors:

- Citing overturned laws as current precedent

- Confusing court decisions with litigant arguments

- Failing to recognize prompt inaccuracies (e.g., validating arguments from a fictional judge)

"Most high schoolers could tell you that state courts don't overrule the Supreme Court, yet these systems do it," notes study co-author Faiz Surani. The core challenge? Legal truth is temporally fluid—a ruling valid today may be nullified tomorrow—which catastrophically confuses large language models.

Why Retrieval-Augmented Generation Fails in Law

Many legal AIs use retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), where systems pull relevant cases before generating responses. But this fails when precedents shift. For example:

# Simplified RAG failure in constitutional law

query = "Does the Constitution guarantee abortion rights?"

retrieved_cases = ["Roe v. Wade", "Planned Parenthood v. Casey"]

response = generate_answer(query, retrieved_cases)

# Outputs "Yes" - ignoring Dobbs v. Jackson's reversal

"Tax law ambiguity compounds this," adds UNC law professor Leigh Osofsky. "When courts disagree on what constitutes a medical expense deduction, there's no single right answer—and AI can't navigate that gray area."

The Accountability Vacuum

As agencies like the IRS explore public-facing AI chatbots for tax guidance, researchers emphasize critical safeguards:

- Explicit disclaimers that outputs aren't legally binding

- Clear ownership chains for AI maintenance and updates

- Integration with domain experts during development

Yet current deployments ignore these principles. The GSA rolled out its "GSAi" tool to 13,000 employees without workflow integration, while the Army's CamoGPT actively modifies policy documents. "They don't care if the AI works for its stated purpose," Young observes. "It's being deployed too fast for narrow use cases."

The Path Forward: Measured Experimentation Over Political Theater

Successful pilots exist—like Pennsylvania's OpenAI collaboration that saved workers 1.5 hours daily on administrative tasks—but they involved controlled, small-scale testing. The federal rush exemplifies a dangerous pattern: deploying brittle technology where errors have constitutional consequences. Until AI can reliably distinguish between settled law and legal fiction, its role in governance must be limited to low-risk辅助任务. As Young starkly concludes: "We're still at the earliest days of assessing what AI is and isn't useful for in governments." The stakes—legal integrity, public trust, and fiscal responsibility—demand we get this right before algorithms start rewriting the rules.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion