Transformers have hit a scaling wall: dense models keep getting bigger, but compute and latency won’t play along. Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) offers a surgical way out—massively increasing capacity while activating only a sliver of parameters per token. Here’s how it works under the hood, why systems teams care, and what you should know before wiring MoE into your own stack.

When Bigger Stops Being Better (At Least Naively)

At frontier-model scale, the old recipe—"add more layers, add more width"—is running into physics and budgets. Dense Transformers burn compute linearly with parameter count; every forward pass slams all neurons for every token. That’s elegant, but at tens or hundreds of billions of parameters, also brutally inefficient.

Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) is the architecture that breaks this symmetry.

Instead of one feed-forward network that everyone must use, you field a team of experts and let each token consult only a few. Capacity soars; per-token compute barely budges. This is not a theoretical curiosity—Google’s GLaM and models like Mixtral-8x7B have already proven that sparse expert routing can compete with, or beat, dense peers at a fraction of the training cost.

Source: This article is based on and expands upon Faruk Alpay’s “Scaling Transformers with Mixture-of-Experts (MoE)” (Medium, 2024).

Core Idea: Routing Instead of Replicating

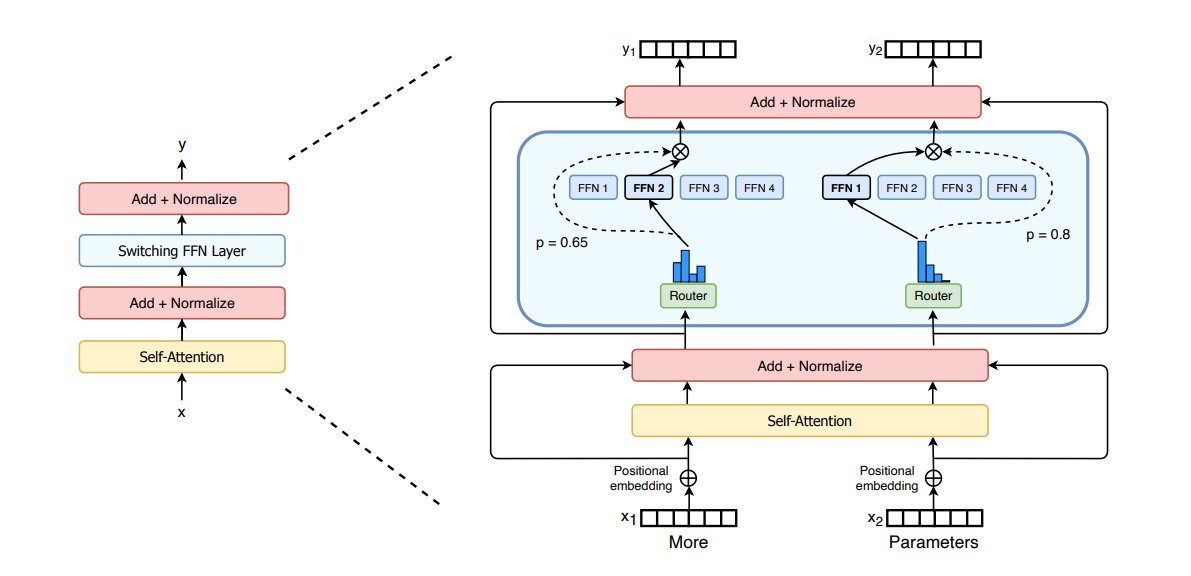

A standard Transformer layer couples attention with a single dense feed-forward network (FFN). Every token passes through the same FFN; every parameter participates in every step.

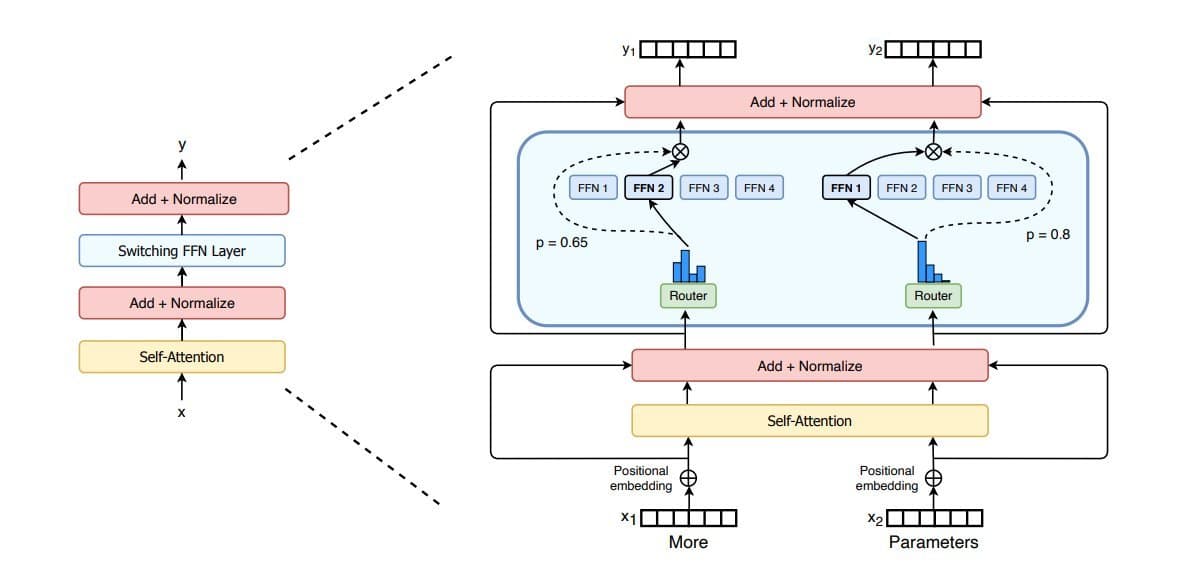

An MoE layer replaces that single FFN with E parallel experts:

- Each expert is an FFN (often large) with its own parameters.

- A lightweight router (or gate) looks at each token embedding and produces scores over experts.

- The model selects the top-k experts for that token (commonly 1 or 2), runs only those experts, and combines their outputs.

Formally, with hidden size d, E experts, and top-k routing:

- Router:

R: ℝ^d → ℝ^Eproduces logits per token. - Softmax over logits → probabilities.

- Select k highest probabilities → dispatch token to those experts.

- Output = weighted sum of selected experts’ outputs.

Key consequence:

- Parameters: scale with

E(you can have 8×, 64×, 100× more capacity). - Compute per token: scales with

k, notE.

That’s the decoupling: you buy huge representational capacity without paying proportional FLOPs.

Real-world examples:

- GLaM: 64 experts with top-2 gating; each token uses only 2 experts—compute comparable to a dense model, parameters far larger.

- Mixtral-8x7B: 8 experts, ~45B total parameters, but per-token compute around a 12–14B dense model because only 2 experts activate.

For practitioners designing inference fleets or training clusters, this is not a micro-optimization; it’s an architectural lever that shifts the economics of scale.

How Routing Actually Works

The router is usually tiny: a single linear projection from the token embedding into expert-logit space, plus a softmax. Conceptually, it acts like attention over experts.

Two main routing regimes dominate:

Soft Routing

- Use the full probability distribution over experts.

- Compute every expert’s output; weight and sum them.

- Easy to optimize, but compute scales with

E—you lose the main advantage.

Hard (Top-k) Routing

- Choose only the top-k experts per token.

- Only those experts compute; others are skipped.

- Achieves sparse activation and real efficiency.

Hard routing introduces its own engineering problems:

- Non-differentiability / instability: mitigated via straight-through tricks or by operating on soft probabilities during backprop.

- Load imbalance: without constraints, a few experts get hammered while others starve.

Production MoE implementations rely on:

- Noisy top-k gating: inject small noise into router logits to encourage exploration.

- Auxiliary load-balancing loss: explicitly penalize uneven expert usage so tokens are spread across experts.

Done right, this yields a healthy distribution where experts specialize without collapsing into a one-expert monopoly.

A Minimal PyTorch Lens (What Actually Runs)

Faruk Alpay’s illustrative PyTorch snippet captures the MoE mechanics:

Expert: a standard two-layer FFN.Router: linear + softmax over experts.MoELayer:- Compute gate probabilities per token.

- Take

topkexperts and renormalize gate weights. - For each expert, collect its assigned tokens, run a forward pass, weight outputs, and scatter back.

The toy implementation loops over experts, but real systems:

- Group tokens per expert into contiguous batches.

- Execute batched GEMMs per expert on GPU/TPU.

- Exploit custom kernels for routing and scattering (e.g., in Megatron-LM, DeepSpeed-MoE, or Hugging Face implementations).

For engineers, the conceptual takeaway is simple:

MoE = (routing op) + (expert-wise batched FFNs) + (load-balancing loss)

Everything else is system design.

Emergent Specialization: Why MoE Works in Practice

One of the most compelling behaviors of MoE is that specialization emerges without explicit labels.

Empirical observations from MoE papers and experiments:

- Encoder experts cluster by token type: punctuation, numbers, connectors, language fragments.

- Continuous MoEs on vision tasks yield experts focusing on specific shapes or digit classes.

This isn’t magic; it’s optimization economics:

- The router learns to send similar inputs to the same experts because that reduces loss.

- Load-balancing losses prevent trivial collapse.

- Each expert effectively sees a biased sub-distribution and can tune aggressively to it.

For model designers, the implication is profound: MoE is not just a compression trick; it's a way to embed inductive structure into otherwise homogeneous architectures, turning a generalist network into a coordinated ensemble of specialists—and doing so end-to-end.

Systems Reality: What You Pay and What You Get

MoE is not a free lunch. It is a very particular trade.

The Upside

Capacity without linear FLOPs growth

- With

Eexperts andtop_kactive, you get roughlyE×parameters at~top_k×FFN cost. - Example: 8 experts, top-2 routing, each expert 10× larger than a baseline FFN → ~80× parameters for ~2× FFN compute.

- With

Better scaling with data abundance

- Large MoEs shine when you have massive corpora and heterogeneous patterns: multilingual, multimodal, code + natural language, etc.

- Instead of one monolithic representation, experts carve up the space.

Flexible capacity planning

- You can dial experts up or down without redesigning attention blocks.

- MoE slots cleanly into existing Transformer stacks as a drop-in FFN replacement.

The Costs and Engineering Headaches

VRAM / HBM footprint

- All expert weights must be resident, even if most are inactive per token.

- Memory scaling is real; MoE often assumes model parallelism or sharded experts.

Routing and communication overhead

- Hard routing means dynamic token → expert assignment.

- On multi-GPU / multi-node setups, this can become an all-to-all shuffle: bandwidth and latency sensitive.

Load balancing and stability

- Poorly tuned routers cause expert collapse or hot-spotting.

- Requires auxiliary losses, gating temperature tuning, and careful initialization.

Implementation complexity

- You likely don’t want to write this from scratch for production.

- Mature frameworks (DeepSpeed-MoE, Megatron-LM MoE, Fairseq, HF Transformers MoE layers) exist, but integrating them with your inference infra, schedulers, caching, and observability stack is non-trivial.

For infra and ML platform teams, MoE is a distributed systems problem as much as an architecture choice. Routing efficiency, kernel fusion, and sharding determine whether the theoretical gains materialize.

When MoE Actually Makes Sense

MoE is not a universal upgrade. It’s an amplifier whose value depends entirely on your regime.

You should seriously consider MoE if:

- You train large language or multimodal models (tens of billions of parameters+) on diverse data.

- You’re compute-constrained but memory-rich (or willing to scale horizontally with sharded experts).

- You run latency-sensitive inference at scale and need higher quality without a linear cost spike.

You should be skeptical if:

- Your model is small or medium-sized; dense FFNs are simpler and often better.

- Your data is narrow-domain; specialized experts won’t have much to specialize on.

- Your infra cannot tolerate complex all-to-all communication.

Think of MoE as a strategic tool for frontier-scale and heterogeneous workloads, not as a default setting for every Transformer.

From Curiosity to Default Pattern

The story around MoE is shifting from "esoteric research idea" to "serious contender for standard large-model design." As more organizations run into the scaling limits of dense Transformers, MoE offers a way to keep pushing capacity without igniting the FLOPs budget.

For developers, the practical guidance is clear:

- Understand the routing and load-balancing mechanics; this is where models fail or thrive.

- Lean on mature libraries; invest your effort in integration, profiling, and monitoring.

- Use MoE where its superpower—targeted specialization at massive scale—actually matters.

In a landscape where parameter counts will keep climbing, Mixture-of-Experts is less a gimmick and more an architectural negotiation: spend memory and complexity to buy back compute and quality. For teams building the next generation of LLMs and multimodal systems, it’s a negotiation worth taking seriously.

Source attribution: This article is adapted from and informed by Faruk Alpay’s “Scaling Transformers with Mixture-of-Experts (MoE)” (Medium, https://medium.com/@lightcapai/scaling-transformers-with-mixture-of-experts-moe-1a361fee46bf), with additional technical context and analysis for engineering and research audiences.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion