AI writing detectors like GPTZero and OpenAI's Text Classifier frequently misidentify human-written classics such as the US Constitution as AI-generated, exposing critical flaws in their underlying technology. Experts reveal these tools rely on unreliable metrics like perplexity and burstiness, leading to high false positive rates that unfairly target students and non-native English speakers. As educators grapple with AI's role in academia, the push for detection may be a misguided solution to a

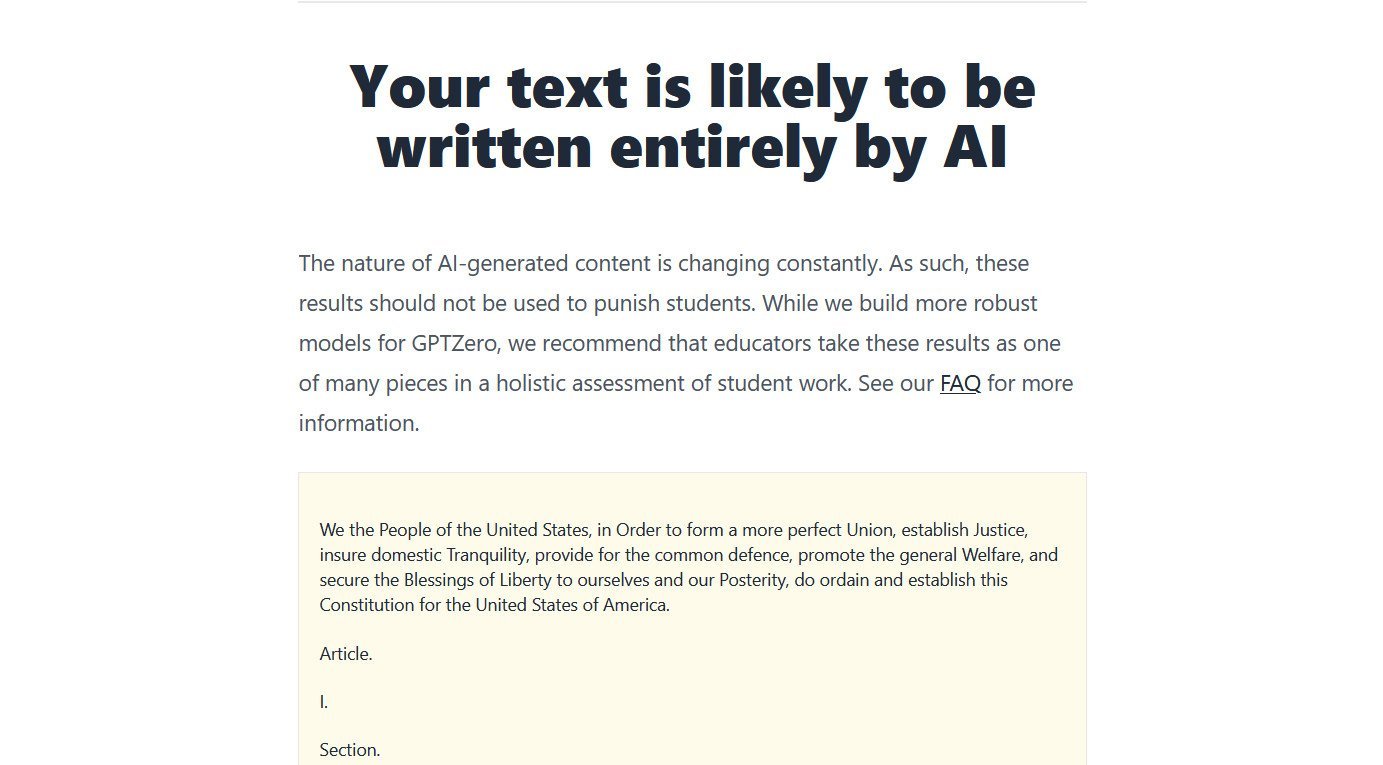

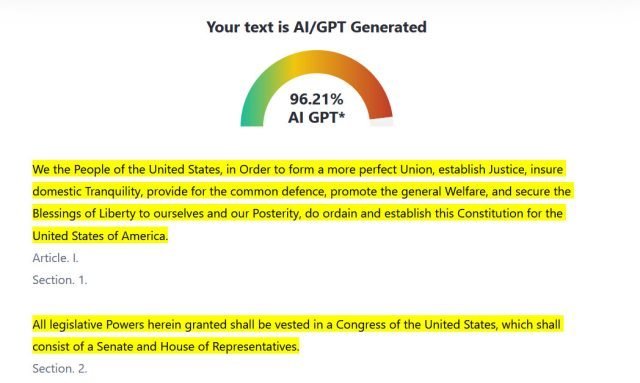

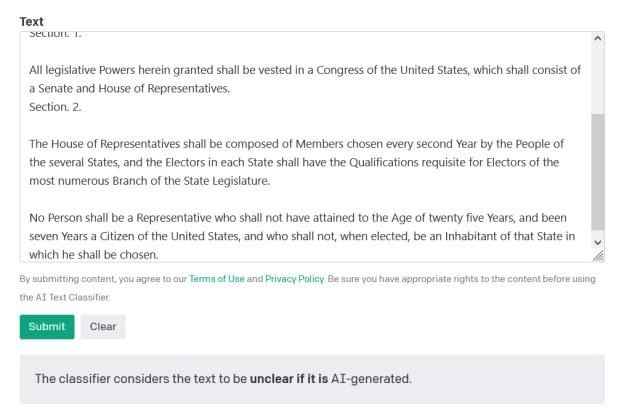

When the US Constitution is fed into AI writing detectors like GPTZero, the result is a jarring false positive: the system declares America's foundational document was "likely written entirely by AI." This isn't an isolated glitch—the same tools flag passages from the Bible and other human-authored classics as machine-generated. The phenomenon has sparked viral debates and dark humor about robotic founding fathers, but it underscores a serious technical crisis. As AI like ChatGPT floods classrooms, educators are increasingly turning to detectors to police academic integrity. Yet mounting evidence reveals these tools are fundamentally unreliable, biased, and potentially damaging. Why do they fail so spectacularly, and what does it mean for the future of writing in the AI era?

The Mechanics of Misidentification

AI detectors operate on a simple premise: they train models on vast datasets of human and AI-generated text, then use statistical metrics to classify new content. The two most common measures are perplexity and burstiness—concepts that sound rigorous but crumble under scrutiny.

Perplexity quantifies how "surprising" a text is relative to a model's training data. As Dr. Margaret Mitchell of Hugging Face explains:

"Perplexity is a function of 'how surprising is this language based on what I've seen?'"

Low-perplexity text (e.g., common phrases like "I'd like a cup of coffee") aligns closely with patterns in the training corpus, making detectors suspect AI involvement. The Constitution's formal, frequently replicated language triggers this flaw—it's so ingrained in AI training data that detectors mistake it for machine output. Edward Tian, creator of GPTZero, confirms this:

"The US Constitution is fed repeatedly into LLM training data. GPTZero predicts text likely to be generated by models, hence this phenomenon."

Burstiness measures sentence variability—humans often mix long, complex sentences with short, punchy ones, while early AI text was more uniform. But this metric is equally flawed. Modern LLMs increasingly mimic human rhythm, and humans can write with machine-like consistency (e.g., legal or technical documents). As AI researcher Simon Willison bluntly states:

"I think [detectors] are mostly snake oil. Everyone desperately wants them to work, especially in education, but they're easy to sell because it's hard to prove ineffectiveness."

The High Cost of False Positives

When detectors err, the consequences are severe. A 2023 University of Maryland study found they perform only marginally better than random guessing, while Stanford researchers demonstrated alarming bias: non-native English speakers face significantly higher false-positive rates due to simpler sentence structures. In education, this has fueled academic witch hunts. Students accused of AI cheating based on tools like GPTZero—which markets itself to universities—must defend before honor boards, presenting evidence like Google Docs histories. As USA Today reported, one student suffered panic attacks despite being exonerated. Penalties range from failing grades to expulsion, yet the detectors enabling these accusations are provably unreliable.

Educators like Wharton's Ethan Mollick argue for embracing AI responsibly rather than policing it poorly:

"There is no tool that can reliably detect ChatGPT-4 writing. They have 10%+ false positive rates and are easily defeated. AI writing is undetectable and likely to remain so."

Toward a Post-Detection Future

The solution isn't better detectors but rethinking writing's role in learning. Mollick suggests educators should focus on whether students understand and can defend their work—not its origins. AI assistance, like calculators in math, can enhance productivity if used ethically. Tian hints at GPTZero's pivot from "catching" students to "highlighting what's most human," but the tension remains between commercial incentives and ethical application. Ultimately, writing reflects human judgment. If an author can't vouch for their facts, AI use is irresponsible—whether detected or not. In a world where machines and humans increasingly co-create, the goal should be cultivating critical thinking, not deploying flawed algorithms as arbiters of truth.

Source: Ars Technica, by Benj Edwards

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion