After 43 days, Congress has voted to end the longest government shutdown in U.S. history — without resolving the core policy dispute that sparked it. Behind the politics lies a quieter crisis: a modern digital state running mission-critical infrastructure on fragile systems that cannot afford this kind of downtime.

The Longest Shutdown Ends. The Technical Debt in U.S. Government IT Just Got Worse.

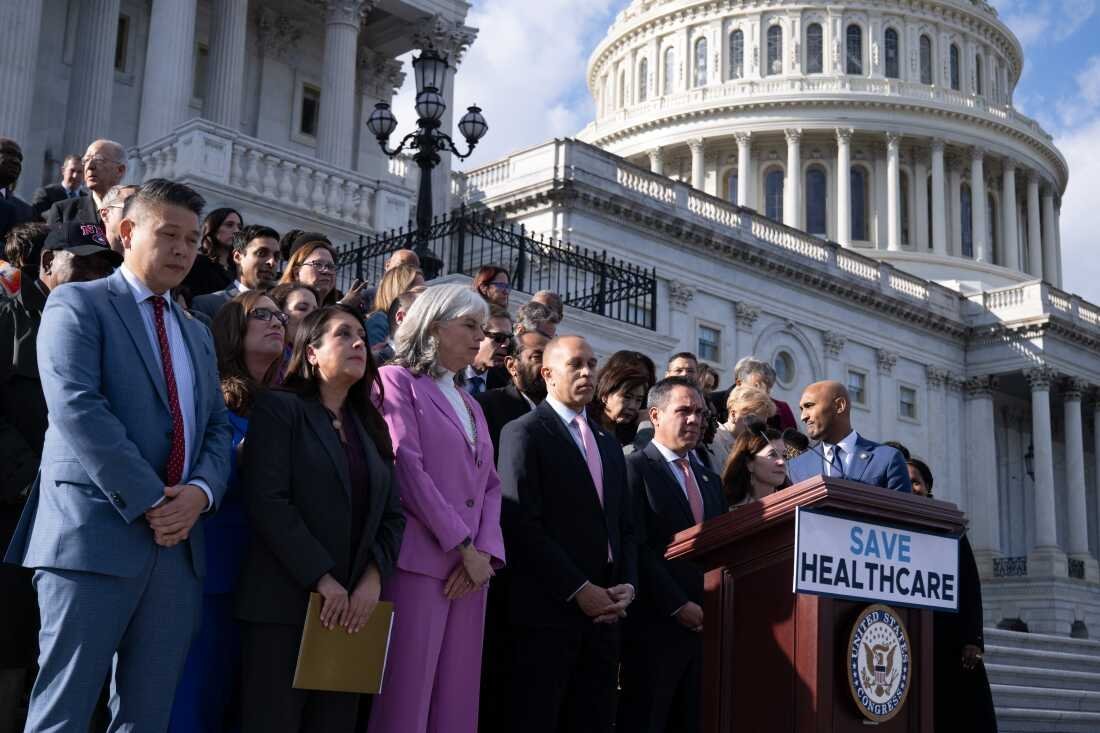

Source: NPR – House votes to end the longest ever government shutdown

On November 12, 2025, the House of Representatives voted 222–209 to fund the government through January 30, ending a 43-day shutdown — the longest in U.S. history. President Trump is expected to sign the bill, sending hundreds of thousands of federal workers back to their terminals, consoles, and queues.

Most coverage will frame this as another bruising episode of partisan brinkmanship over health-care subsidies and short-term funding. But for anyone who builds or operates systems at scale, this was something more alarming: a live-fire demonstration of how politically induced downtime collides with brittle public infrastructure, critical software, and the people who keep it all running.

This shutdown wasn’t just about missed paychecks. It was an outage in the operating system of the state.

What Actually Happened (Without the Spin)

The bill:

- Extends last year’s spending levels through January 30 for most of the government.

- Fully funds some agencies through next September, including payments for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).

- Restores backpay for federal employees and reverses shutdown-driven layoffs.

- Adds protections against further layoffs tied to this episode.

Crucially, it does not resolve the core fight: the expiration of enhanced Affordable Care Act (ACA) subsidies at year’s end. Instead, Senate Majority Leader John Thune agreed to a mid-December vote on a Democratic proposal to extend those subsidies — a “handshake deal” many Democrats openly distrust.

In other words: the system is booting back up, but only into a temporary session.

When Governance Acts Like a Fragile Production System

For technologists, several themes from this shutdown map uncomfortably well to problems we know from production systems:

"We’ll fix it later" technical debt

- Federal systems — from benefits platforms to transportation infrastructure — already operate under decades of accumulated technical and regulatory debt.

- Shutdowns add a new layer: unpredictable freezes in funding, hiring, modernization, and security programs.

- Every time government runs on a stopgap, it’s the equivalent of running prod on an expired trial license and promising the team you’ll "sort it out next sprint."

Forced downtime on always-on systems

- SNAP serves roughly 42 million Americans. Payment interruptions aren’t a feature toggle; they’re a systemic failure with immediate human consequences.

- Air traffic control and TSA operations continued, but with unpaid staff and mounting stress, forcing the FAA to scale back flights. In SRE terms: you kept SLOs by burning out the on-call.

- Critical security, compliance, and continuity work inside agencies was delayed or deferred; patches, audits, and upgrades don’t stop being necessary just because Congress does.

Policy as a single point of failure

- Tying core government uptime to a single, unresolved policy dispute (ACA subsidies) is the political equivalent of putting your authentication, billing, and monitoring behind one experimental gateway.

- When failure in a negotiation can throttle food aid, aviation capacity, research programs, and security operations, your architecture is wrong.

For engineers, the lesson is clear: the reliability of public services is not only a software problem. It’s an architectural problem at the interface of code, institutions, and law.

Shutdown Fallout: The Hidden Infra and Security Costs

Most of the damage won’t show up in vote tallies or cable news hits. It will show up in:

Delayed modernization projects

- Cloud migrations in agencies like USDA, HHS, and DHS often hinge on milestone-based funding; a 43-day freeze cascades into missed vendor timelines, stalled decommissions, and prolonged reliance on legacy systems.

- Multi-year refactors — identity systems, case management platforms, benefits disbursement rails — now lose schedule and trust, increasing the temptation to "just extend the old system one more year."

Eroded cybersecurity posture

- Federal agencies are high-value targets. During shutdowns, red teams, patch cycles, log analysis, and modernization projects are often slowed or paused.

- That’s free signal for adversaries: fewer humans watching, stretched resources, delayed detection.

- Even with skeleton crews, the risk profile changes. Anyone running a SOC knows what happens when you operate critical defense with max fatigue and minimum coverage.

Talent and culture damage

- Experienced federal technologists, SREs, cybersecurity staff, and data engineers already fight compensation gaps to stay in public service.

- Repeated shutdowns make that decision harder. Top talent won’t build their careers on an org that might "suspend prod" for six weeks for reasons unrelated to system health.

- The long-term cost: fewer people willing to modernize critical public systems from the inside.

These aren’t abstractions. They’re the same dynamics your teams fight against in private-sector infrastructure — except here the blast radius is national.

What Tech Leaders Should Learn from a 43-Day Government Outage

Even if you never touch .gov systems, this shutdown offers sharp lessons for anyone building critical platforms.

Don’t tie core uptime to unrelated battles

- In architecture: you don’t block auth or payments on whether a new feature flag framework ships.

- In governance: you don’t tie SNAP, aviation safety, or security ops to unrelated policy demands.

- For enterprises: avoid organizational structures where essential services depend on optional strategic fights (e.g., holding production deployments hostage to internal politics).

Design for political and organizational chaos

- Critical infrastructure should be resilient not just to hardware or cloud-region failure, but to governance volatility: budget uncertainty, leadership changes, legal challenges.

- In practice, that suggests:

- Long-term ring-fenced funding for cybersecurity and maintenance.

- Automated, well-documented runbooks so emergency operations don’t rely on heroics.

- Architectures that reduce manual toil when staff capacity is constrained.

Build verifiable, not handshake, guarantees

- Tech culture has its own version of "handshake deals": unwritten SLOs, informal promises, “we’ll prioritize that security work later.”

- The shutdown’s ending via a non-binding pledge on ACA subsidies is a reminder: if it’s not encoded (in law, in contracts, in processes, in tests), it’s fragile.

- For engineering orgs, that means:

- Explicit SLOs tied to monitoring.

- Documented escalation paths and funding commitments for infra and security.

Recognize that public infra is part of your dependency graph

- If you run logistics, healthcare, fintech, travel, or supply chain platforms, government systems are in your extended architecture: TSA operations, FAA flight capacity, benefits disbursement, identity verification, research data.

- Government shutdowns behave like third-party platform outages — ones you can’t just switch providers for.

- Risk modeling should treat political instability as a real (if uncomfortable) input.

If We Treated Government Like We Treat Critical Production

Imagine applying standard reliability thinking to what we’ve just watched:

- No SRE would accept an environment where a key stakeholder can unilaterally halt ops for 43 days.

- No principal engineer would design benefits, security, and transportation systems to all hinge on a short-term continuing resolution with a known, contentious deadline.

- No mature org would call "we got a promise to maybe fix it next month" an acceptable post-incident remediation.

Yet that is effectively how the federal digital state is being run.

Ending this shutdown is good. Essential workers will be paid. SNAP can resume. Systems can unfreeze. But underneath the relief is a worsening form of infrastructural and institutional technical debt — one that can’t be patched with another 60-day fix.

For the people who build and secure critical systems, the takeaway is sobering: reliability engineering principles now need to be part of how we think about democratic resilience. If we insist on treating essential public services as bargaining chips, we should stop being surprised when the system behaves like an underfunded monolith held together by exhausted maintainers and wishful thinking.

The longest shutdown in history is over. The question for technologists is whether we treat it as background political noise — or as the most important postmortem of the year that nobody in power seems willing to write.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion