Valve is resurrecting the Steam Machine idea—but this time with a mature SteamOS, a semi-custom RDNA 3 GPU, and a thermally elegant, near-silent cube designed for the 4K TV era. For developers and PC enthusiasts, it’s more than a console competitor: it’s a statement about the future of open, Linux-first gaming PCs.

Valve’s Second Shot at the Steam Machine Is the Living Room Linux PC That Finally Makes Sense

When Valve first pitched Steam Machines in 2013, the idea was intoxicating: console-like simplicity, PC openness, and a Linux-based SteamOS that would break Windows’ lock on gaming. The execution was a mess. Fragmented OEM boxes, immature drivers, thin game compatibility, and no clear hardware story. By 2018, the effort was pronounced dead.

But Valve never stopped building the missing pieces.

SteamOS quietly evolved. Proton went from science project to workhorse. The Steam Deck arrived and proved that Linux gaming at scale wasn’t just viable—it could be delightful. And now, for 2026, Valve is ready to do what it tried a decade ago: a first-party, tightly integrated Steam Machine.

This time, the hardware, software, and audience might actually be ready.

“We finally have all the software and the hardware bits to make the original vision a reality,” says Valve engineer Yazan Aldehayyat.

A Console-Simple Spec Sheet With PC Intentions

On paper, the new Steam Machine is unassuming. Under its compact shell:

- CPU: 6-core/12-thread AMD Zen 4

- GPU: Semi-custom AMD RDNA 3, 28 CUs @ ~2.4–2.5 GHz, ~110–130 W TDP

- RAM: 16 GB DDR5 (SO-DIMM, replaceable)

- Storage: 512 GB or 2 TB NVMe (2230, user-accessible; 2280 supported with caveats)

- Connectivity: Wi‑Fi 6E, Bluetooth, 1 GbE

- Ports (front): 2x USB 3.0 Type-A, microSD

- Ports (rear): 2x USB 2.0 Type-A, 1x USB 3.2 Gen 2 Type-C (10 Gbps), Ethernet, HDMI 2.0, DisplayPort 1.4

- PSU: 200 W internal

- Target launch: 2026

- Price: TBA (but expectations are clearly in the “deck-adjacent, mass market” tier)

The spec story is less about brute force and more about constraint as a design principle.

A 200 W budget is an order of magnitude under many modern gaming rigs, but this isn’t trying to outgun enthusiast towers. Valve is designing for:

- Living room thermals

- 4K TVs as primary displays

- Console-like acoustics

- Power efficiency that doesn’t trip breakers or melt cabinets

Aldehayyat is blunt about the performance target:

“Our benchmark has always been that it should have enough performance to play every game on Steam at 4K60 when you do some sort of upscaling like FSR.”

That’s ambitious—borderline provocative—given the power envelope. In hands-on demos with Cyberpunk 2077 at 4K using FSR, performance was “playable” but not buttery; 1080p without upscaling felt much smoother. Anyone expecting native 4K/Ultra parity with 300 W GPUs will be disappointed. Anyone expecting a living room PC that can sensibly trade image quality, resolution, and FSR to hit solid frame rates will see exactly what Valve is building.

For developers, that target is a signal: optimize for upscaling, tune for a mid-range GPU class, and expect a Linux-first runtime.

The Semi-Custom RDNA 3 Heart

The GPU is where this box becomes more than a Steam Deck on AC power.

Valve’s semi-custom RDNA 3 design:

- 28 compute units

- ~2.4–2.5 GHz clocks

- Navi 33–derived, but not a 1:1 match with any desktop SKU

- TDP in the 110–130 W range

The nearest cousins in AMD’s public lineup are:

- Radeon RX 7400: also 28 CUs, but clocked and powered lower

- Radeon RX 7600M: 28 CUs @ ~2.41 GHz, up to 90 W

The Steam Machine’s chip effectively stretches that laptop-class silicon into a small-box, better-cooled form factor. That could allow more sustained boost clocks and tighter thermals than a gaming laptop, without venturing into the chaotic territory of full-fat desktop cards.

This choice is philosophically on brand:

- Console-like: fixed-ish target, tightly optimized.

- PC-like: standard(ish) RDNA 3 behavior, Vulkan/DirectX via Proton, open OS.

For engine teams, this is a comforting target: optimize for an efficient RDNA 3 baseline and you’ll hit not just Steam Machines, but handheld PCs and a broad segment of real-world gaming rigs.

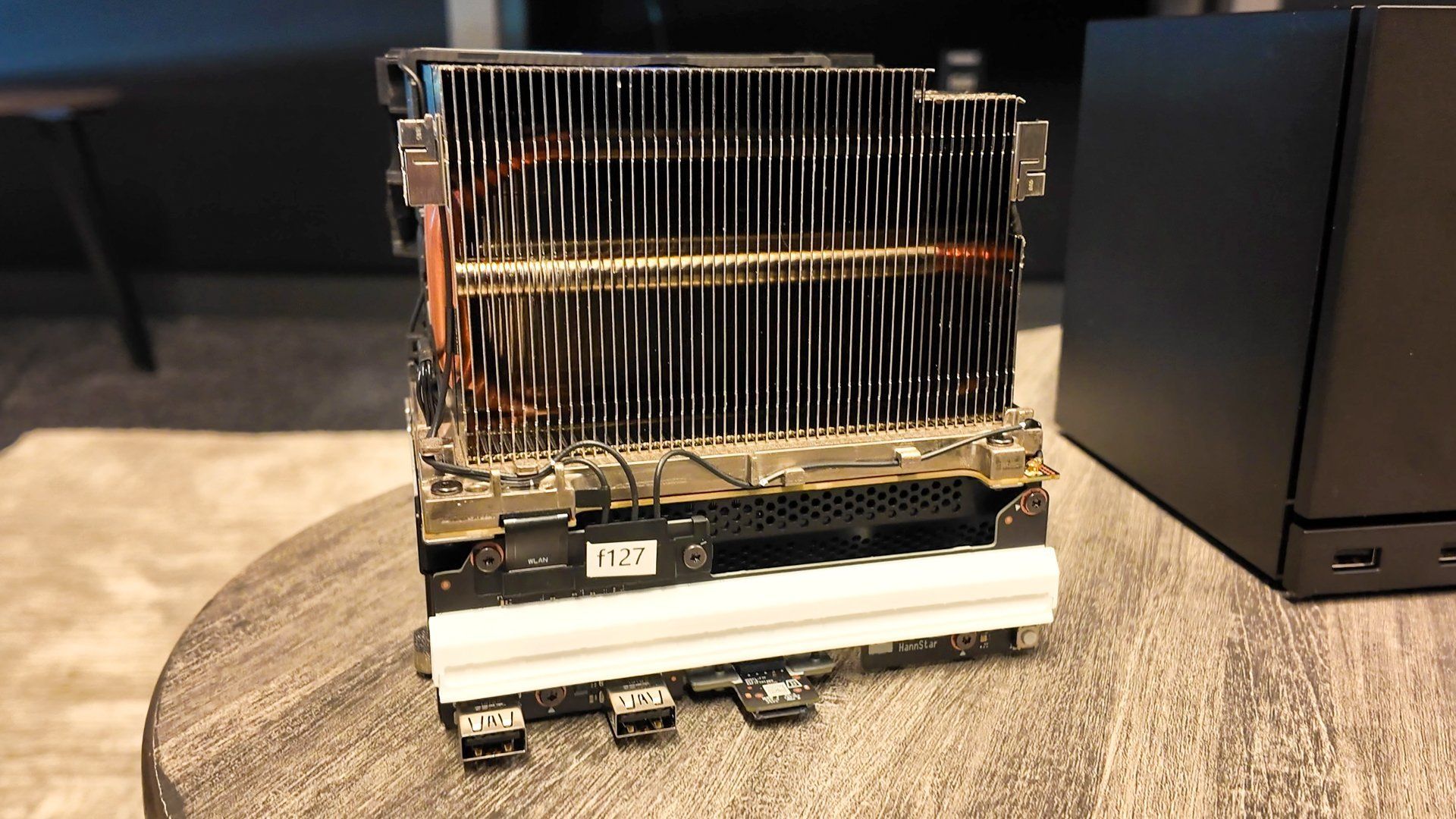

A Cube Engineered Backwards From Airflow and Silence

The original Steam Machines looked like set-top boxes afraid of being PCs. The new Steam Machine leans into being an engineered object first, living room appliance second.

Visually, it’s a near-cube. That’s not a gimmick; it’s thermodynamics.

Valve engineer Jeff Mucha explains that the final shape emerged from thermal, acoustic, and dimensional constraints (notably, fitting inside a 6-inch shelf). The result is a chassis where:

- The integrated PSU forms the structural base and part of the RF shielding.

- The motherboard lives directly above it.

- A single, large heatsink spans CPU, GPU, memory, and power delivery.

- One custom 120 mm rear fan pulls air efficiently through the stack.

“We’re using the power supply as the chassis for the system,” Aldehayyat notes, calling out the reduced brackets, simplified RF shielding, and denser packaging.

This is server thinking applied to a living room box: serialize airflow, eliminate turbulence, overbuild the shared heatsink, then slow down a big fan until it disappears acoustically.

In demos, sitting next to the Steam Machine idling on the Cyberpunk 2077 title screen, it was effectively inaudible. For a device destined for media cabinets, that matters more than RGB theatrics.

Other design touches show a similar priority stack:

- Four discrete antennas: two rear for Wi‑Fi 6E, one front for Bluetooth, one dedicated to Steam Controller connectivity.

- A removable front faceplate for dust cleaning—with the possibility (not promise) of themed or even e-ink variants.

- A subtle front light strip that can visually signal downloads, notifications, or activity—and vanish entirely when disabled.

Mucha calls it a “dead front design”: powered off, it looks like nothing. Powered on, it behaves like an ambient-aware console.

For hardware architects, there’s something quietly radical here: using PSU-as-chassis and a monolithic thermal stack to collapse BOM, simplify EMI compliance, and still deliver user-serviceable storage and RAM. This is small-form-factor design that respects both the living room and the right-to-tinker crowd more than most proprietary consoles ever have.

Upgrades Without Betraying the Form Factor

Valve’s stance on upgradability is pragmatic, not performative.

What’s realistically user-upgradable:

- Storage:

- 1x easily accessible NVMe slot (2230), shipping in 512 GB or 2 TB configs.

- Mechanical support for 2280 with the included standoff (requires swap/clone).

- microSD (SDXC up to 2 TB) as a sanctioned, performance-acceptable expansion path.

- Memory:

- 16 GB DDR5 SO-DIMM, technically replaceable.

- But: requires deeper disassembly past the heatsink—doable for enthusiasts, not encouraged for everyone.

Valve is drawing a clear line: this is not a modular PC kit in disguise. It’s a semi-fixed platform with:

- Easy, expected upgrades (storage).

- Possible, warranty-in-question upgrades (RAM).

- No fantasy GPU slots that would shatter the thermal model and support burden.

From an ecosystem point of view, that’s a net positive. Developers get a stable performance target. Power users still have meaningful levers. OEM chaos is kept out of the critical path.

SteamOS and Proton: The Real Play Here

Hardware makes this box interesting. Software is what makes it strategic.

“Proton is really the secret sauce,” Aldehayyat says. He’s not wrong.

What killed the first Steam Machine wave wasn’t just hardware confusion—it was Linux being functionally incompatible with a huge swath of the Windows-native PC catalog. Proton changed that. The Steam Deck battle-tested it at consumer scale.

On the new Steam Machine:

- SteamOS is the same Deck-like interface: controller-native, TV-friendly, familiar.

- Proton runs the vast majority of Windows titles without dev-side porting.

- Linux-level overhead reductions can translate into meaningful FPS gains versus Windows, especially on constrained hardware.

We’ve already seen scenarios—such as Cyberpunk 2077 on the Legion Go—where SteamOS delivered up to 30% better performance compared to Windows 11 on the same silicon. On a 200 W box, that delta is the difference between “compromise” and “this feels fine on my couch.”

There are caveats, and they’re important:

- Some major anti-cheat stacks (and thus games like Fortnite and Battlefield 6 at time of writing) still don’t reliably support Linux/Proton.

- Verified status, so central to the Steam Deck’s UX, is less necessary but expectations for “it just works” on a living-room PC will be higher.

Valve’s counterbalance is philosophical and practical:

- It’s still a PC. Users can wipe it and install Windows 11 if they insist.

- The company is openly committed to the “open PC ecosystem,” not a walled garden.

For game studios and tech leads, the message beneath the marketing is sharper: Linux/Proton is no longer a hobbyist corner. With Steam Deck, Steam Machine, and the broader Proton install base, ignoring Linux compatibility is now a business decision, not a default.

Why This Steam Machine Actually Matters

The new Steam Machine is not the most powerful gaming PC, nor is it aiming to be. It matters because of what it normalizes.

If Valve ships this with a compelling price point in 2026—and its history with the Steam Deck suggests it will—the industry gets:

- A credible, mass-market Linux gaming box in the living room.

- A stable RDNA 3–class performance target for developers.

- A tangible alternative to the Windows + big-GPU monoculture.

For developers:

- Targeting Proton and Vulkan becomes less of a “nice to have” and more of a practical optimization path.

- FSR, temporal upscalers, and efficient rendering techniques aren’t fringe tech—they’re the foundation of hitting 4K on realistic power budgets.

- QA matrices expand to include SteamOS as a serious tier, not an afterthought.

For PC builders and system designers:

- Valve’s PSU-integrated chassis, single-fan shared heatsink, and antenna separation choices are a compelling blueprint for future SFF designs.

- It demonstrates that you can build something console-simple without fully sacrificing repairability or OS freedom.

For players:

- You get a console-like box that runs your Steam library, respects your ownership, and doesn’t lock you into a single OS or storefront.

The first generation Steam Machines asked the market to take a leap of faith on incomplete infrastructure. The 2026 Steam Machine is the inverse: it arrives after the infrastructure—SteamOS, Proton, driver maturity, Deck-learned UX—has already proved itself.

Valve isn’t just reviving an old idea. It’s quietly rewriting what a “default” gaming PC can look like in an era where efficiency, openness, and platform independence suddenly matter again.

Source: Original reporting and technical details based on PC Gamer’s coverage: https://www.pcgamer.com/hardware/gaming-pcs/steam-machine-specs-availability/

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion