Forty years after its launch, the Commodore Amiga is celebrated not just as a PC pioneer but as the canvas for Andy Warhol’s groundbreaking digital art experiments. Warhol’s live 1984 portrait of Debbie Harry at the Amiga’s debut event marked the dawn of accessible creative computing, a legacy almost lost until floppy disks resurfaced in 2014. This moment underscores how the Amiga democratized art, music, and multimedia—decades before today’s tools.

This month marks the 40th anniversary of the Commodore Amiga 1000’s release, a machine that helped catalyze the PC revolution alongside icons like the Macintosh. With its 16/32-bit Motorola 68000 CPU, revolutionary graphics and sound capabilities, and a multitasking OS running on just 256 KB of ROM, the Amiga was billed as a business tool but quickly became a creative powerhouse. Its legacy in gaming, animation, and digital artistry remains influential, but one cultural moment epitomizes its impact: Andy Warhol’s surreal live demo at its 1984 launch.

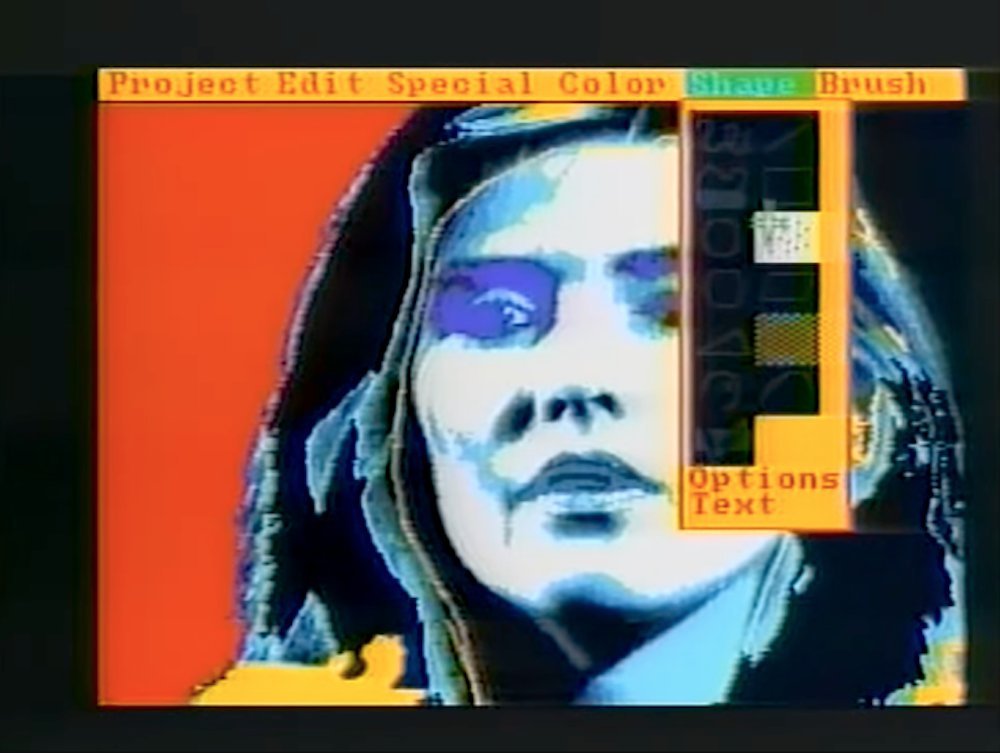

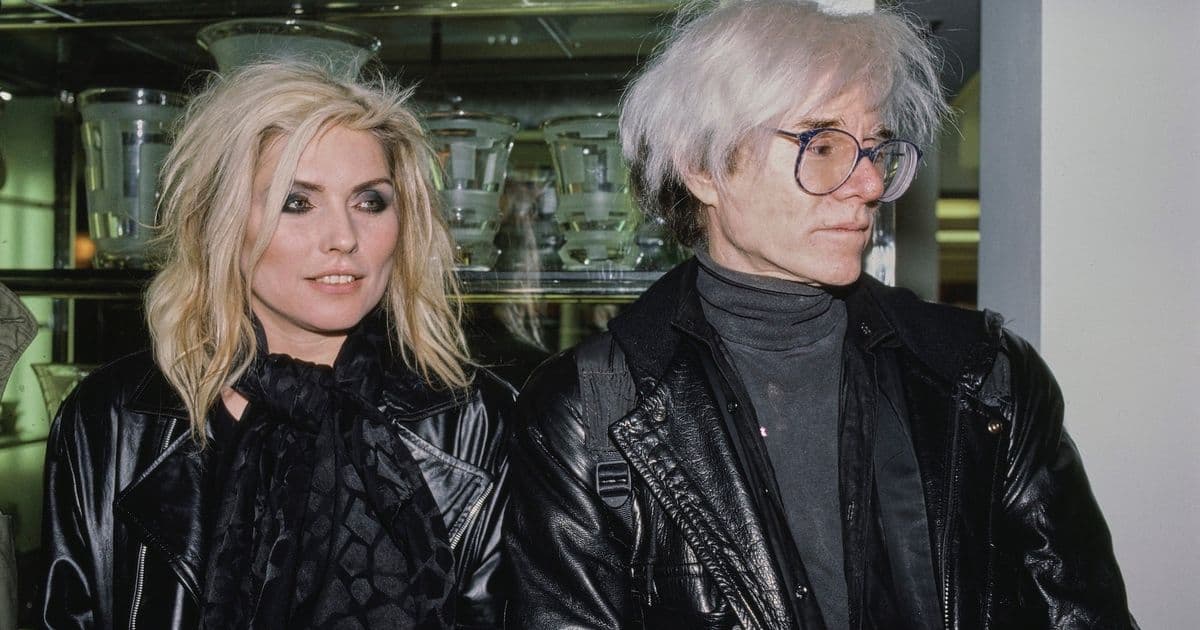

At a black-tie event at New York’s Lincoln Center on July 23, 1984, Warhol used the Amiga 1000 and ProPaint V27 software—a precursor to tools like MS Paint—to create a digital portrait of Blondie’s Debbie Harry. Guided by Amiga artist Jack Haeger, Warhol captured a "digital snapshot" of Harry, then layered it with vibrant color fills. The brief, awkward exchange that followed hinted at his fascination: "You found it to be spontaneous?" Haeger asked. "Yeah it’s great. It’s such a great thing," Warhol replied flatly, as the audience laughed. This demo kicked off a three-year brand ambassadorship, during which Warhol used his gifted Amiga to reimagine classics like Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus and his own Campbell’s soup cans.

In a 1986 interview with Amiga World, Warhol reflected on the machine’s disruptive potential:

"The thing I like most about doing this kind of work on the Amiga is that it looks like my work in other media. Mass art is high art."

His experiments, however, nearly vanished. For decades, Warhol’s Amiga creations were presumed lost until 2014, when the Andy Warhol Museum rediscovered them on floppy disks in its archives. Matt Wrbican, the museum’s chief archivist, noted the significance:

"We see a mature artist grappling with the bizarre new sensation of a mouse in his palm... It marked a huge transformation in our culture."

Warhol’s work on the Amiga wasn’t just art—it was a prophecy. He envisioned computers as holistic creative tools, telling Amiga World:

"An artist can really do the whole thing... make a film with everything on it, music and sound and art."

This ethos foreshadowed today’s integrated creative suites, from Adobe Creative Cloud to AI-generated multimedia. The Amiga’s hardware—once cutting-edge—now feels quaint, but Warhol’s exploration of its limits revealed a truth: technology doesn’t just enable art; it redefines what art can be. As we celebrate four decades since that Lincoln Center spectacle, Warhol’s floppy-disk masterpieces remind us that innovation in tech is often painted in bold, unexpected strokes.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion