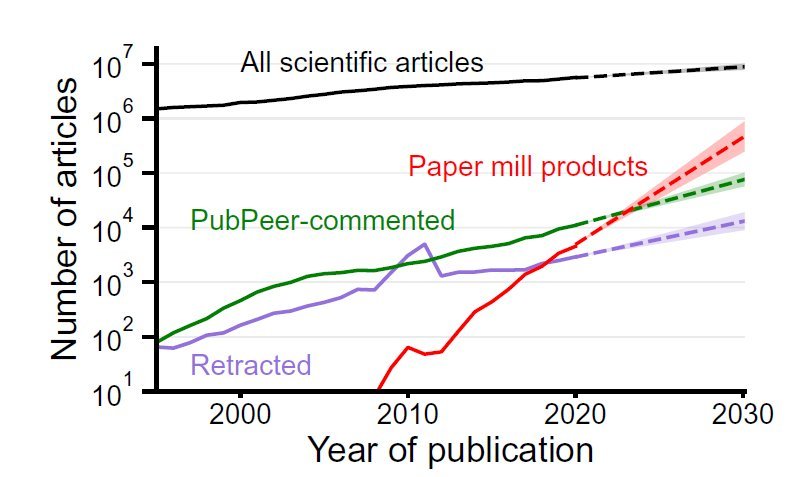

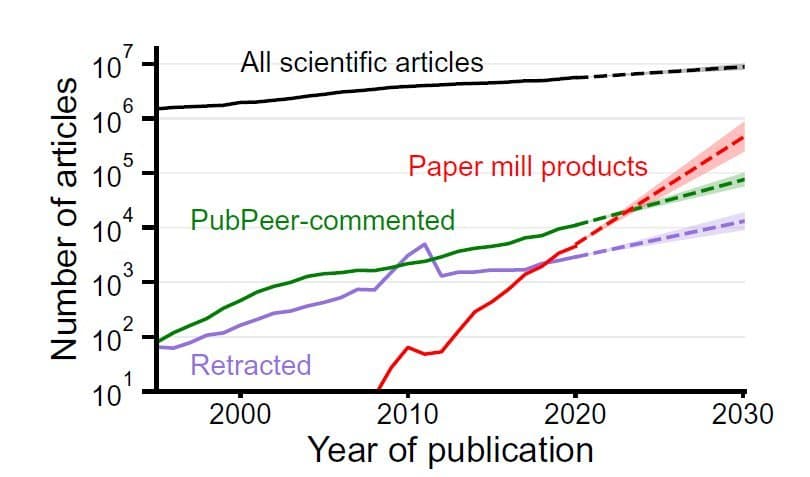

A groundbreaking study in PNAS reveals that systematic research fraud, fueled by paper mills and predatory publishers, is growing at more than twice the rate of corrective actions like retractions and PubPeer flags. With only 28.7% of suspected fraudulent papers ever retracted, the findings expose a critical threat to scientific integrity that demands urgent, global collaboration. The research underscores the need for advanced detection tools and a fundamental shift in research incentives to ste

Scientific publishing is drowning in a flood of fraudulent research, and the buckets meant to bail it out are no match for the deluge. According to a landmark study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), paper mills—shadowy operations that mass-produce fake or low-quality papers for profit—alongside predatory publishers and authorship brokers, are accelerating research fraud at an alarming pace. The analysis, led by Luis Amaral of Northwestern University, shows suspected paper mill products double more than twice as fast as corrective measures, whether through formal retractions or crowdsourced platforms like PubPeer. As coauthor Amaral starkly put it: "It’s like emptying an overflowing bathtub with a spoon."

The Anatomy of a Crisis

Using metadata from over a decade of publications, the researchers mapped networks of fraud across major publishers like PLOS One, IEEE, Springer Nature, and Elsevier. They combined data from Scopus, Clarivate’s Web of Science, the Retraction Watch Database, and PubPeer comments to identify patterns invisible to traditional peer review. Key findings include:

- Editorial Compromise: In PLOS One, a network of just 45 editors handled 1.3% of all articles but were responsible for 30.2% of retractions. Over half of these editors also authored retracted papers, suggesting deep-seated collusion.

- Conference Vulnerabilities: IEEE conference proceedings showed hundreds of events with abnormally high retraction or flagging rates. Seven conference series were flagged every year they ran, highlighting systemic issues in peer-review oversight.

- Image Duplication Networks: An innovative analysis revealed clusters of papers with duplicated images published in close succession—34.1% of these were retracted, pointing to coordinated fraud. Anna Abalkina of Freie Universität Berlin noted: "It is fascinating to see how paper mills expand like an octopus, engaging more scholars in the network."

The Tools and Tactics of Detection

The study pioneers high-throughput methods to combat fraud, such as:

"Using rare signals like PubPeer comments on image duplication or tortured phrases, we can uncover what’s invisible. That’s the job of metascientists—to turn public indicators into actionable insights," said Reese Richardson, a coauthor and postdoctoral researcher at Northwestern.

Reese Richardson, coauthor of the PNAS study, emphasizes the role of metascience in fraud detection.

Reese Richardson, coauthor of the PNAS study, emphasizes the role of metascience in fraud detection.

For instance, the team analyzed RNA biology subfields, where compromised areas saw retraction rates soar to 4% compared to 0.1% in unaffected fields. They also tracked "journal hopping" by brokers like the Academic Research and Development Association (ARDA), which shifted focus to new journals as others were de-indexed—33.3% of ARDA-linked journals lost indexing versus 0.5% industry-wide.

Why This Matters for Tech and Research

This fraud epidemic has dire implications:

- Erosion of Trust: Fabricated research in fields like AI or biomedical engineering could derail innovation and policy decisions.

- Resource Drain: Universities and publishers waste millions investigating fraud instead of advancing science.

- Tooling Gap: Current AI-based plagiarism checkers can’t easily detect sophisticated paper mill outputs, underscoring the need for better ML-driven solutions.

A Call for Collective Action

The researchers urge a global response akin to addressing climate change, involving bodies like the U.S. National Academies and the U.K. Royal Society. Actions include:

- Overhauling Incentives: Reduce hyper-competition for grants and publications that fuel fraud.

- Scaling Detection: Develop automated tools for image and data anomaly spotting.

- Community Vigilance: Scientists must engage in post-publication peer review on platforms like PubPeer.

As the bathtub overflows, the study is a rallying cry: only united, systemic change can preserve science’s foundation. Or as Amaral asserts, "We need the biggest stakeholders to implement standards—not wait for the problem to solve itself."

Source: Retraction Watch, August 4, 2025, based on R. Richardson et al., PNAS 2025.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion