A viral writing challenge hides a serious operating principle for developers and engineering leaders: deliberate, public repetition rewires your capabilities faster than perfectionism ever will. Here’s how the ‘do 100 things’ mindset maps directly to code, infra, AI, and shipping real systems that don’t fall over.

)

)

The Meme That’s Actually an Engineering Pattern

On its face, “Do 100 things” sounds like another internet self-improvement dare:

Do 100 crappy things, with no agenda, at whatever pace — and you’ll get better.

Originally popularized by @visakanv and recently chronicled by Sasha Putilin in his Substack piece "Do 100 things (5/30)" (Source: https://psychotechnology.substack.com/p/do-100-things-530), the challenge is simple: pick a craft, do it 100 times, in public. Don’t overthink quality. Just ship.

For software teams, this is more than motivational poster material. It’s an operating system.

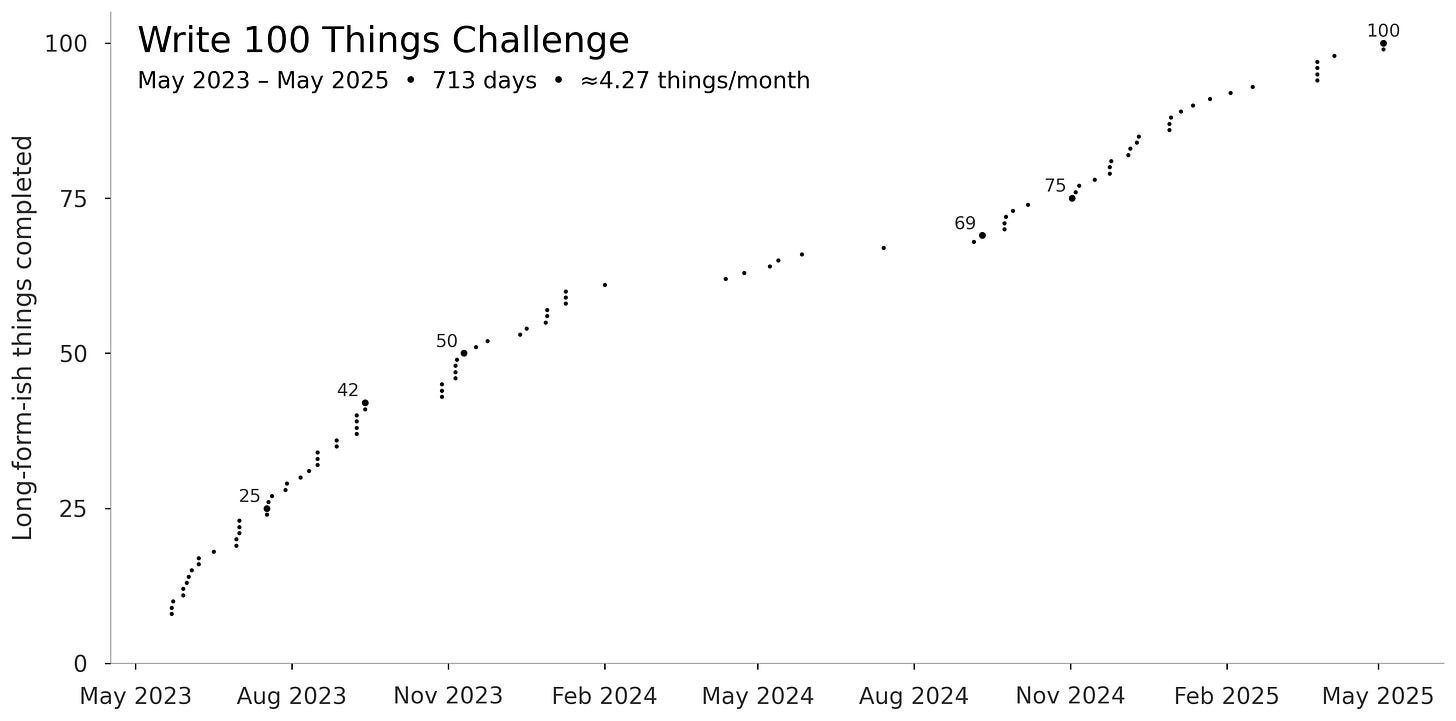

Putilin’s experience — tracking 100 “long-form-ish” pieces over two years, from Substack essays to creative DMs and emails — reads like a case study in incremental system tuning: noisy at first, uneven in the middle, then a phase shift where the work stops feeling scarce and starts feeling inevitable.

That curve is deeply familiar to anyone who’s built production systems, scaled infra, or iterated on an ML product. The takeaway: volume, with closure, compounds into capability.

Quantity as an Engineering Primitive

Putilin frames one crucial constraint: it only counts when you hit send.

Journaling doesn’t count. Drafts don’t count. It has to cross a boundary: to a subscriber list, to a map review, to another human in a DM.

For a technical audience, that maps cleanly to:

- A feature branch doesn’t count.

- A half-written RFC doesn’t count.

- The code that "works on my machine" doesn’t count.

What counts is:

- Merged PRs that survive review.

- RFCs circulated, discussed, and revised.

- Observability dashboards deployed and used.

- CI pipelines green for real workloads.

- Tiny tools published, internal packages versioned, docs merged.

The natural cutoff is deployment or publication — the point where the system, or your thinking, is exposed to reality. That exposure is where learning density spikes.

Putilin’s insight (backed by his own log of 100 outputs) is that the act of closing the loop is itself the training signal. The same applies when you:

- Ship 100 small services instead of architecting one perfect monolith in your head.

- Run 100 incident postmortems instead of just “being more careful.”

- Execute 100 CI/CD improvements instead of one doomed "big bang" platform migration.

Engineers don’t become senior by merely understanding systems; they become senior by repeatedly finishing things that matter, where failure is visible and recoverable.

The Phase Shift: From Scarcity to Systems Thinking

One of the most interesting moments in Putilin’s narrative is right near the end.

Somewhere around items 90–95 — before hitting the magic 100 — something flips. Writing stops being an event and becomes a habit. The counter loses its psychological grip. The skill has stabilized into identity.

You’ve likely seen the same thing in engineering orgs:

- The team that’s shipped a dozen production services no longer treats releases as trauma; shipping is just what they do.

- The SRE group that’s run 50+ game days doesn’t panic during a real incident; they’re executing muscle memory.

- The ML team that’s iterated through 100+ model experiments isn’t "trying AI"; they’re operating an experimentation system.

The 100-things pattern is really about reaching that phase shift:

- Initial outputs: Awkward, over-engineered, emotionally expensive.

- Middle run: Inconsistent; lots of gaps, still identifying patterns; tooling, style, and taste begin to emerge.

- Late run: Friction collapses; decisions compress; feedback integration becomes intuitive; the system (you, your team, your platform) knows how to ship.

From a technical leadership perspective, you’re not just optimizing for output; you’re designing the conditions in which this phase shift becomes inevitable:

- Lower blast radius so people are safe to ship.

- Tight feedback loops so each "thing" teaches something.

- Public-enough artifacts (PRs, ADRs, internal posts, changelogs) so work leaves a trail.

That’s the infrastructure of mastery.

Why Crappy Things Beat Perfect Intentions

Engineers are especially vulnerable to the perfection tax.

You’ve heard its slogans:

- "We’ll refactor it properly when we have time."

- "Let’s design the full platform before adding more services."

- "We can’t release this experimental feature; it’s not elegant yet."

The “Do 100 things” ethos attacks that directly. In Putilin’s retelling of Visakan Veerasamy’s original framing — “Do 100 Crappy Things For No Reason, With No Agenda” — the key is decoupling practice from grandeur.

For developers, that looks like:

- Build 100 tiny CLIs, internal tools, or scripts before worrying about "my big open-source framework."

- Write 100 docs: setup guides, runbooks, postmortems, design notes. Let clarity accumulate.

- Run 100 lightweight experiments with your infra-as-code, observability, or AI integration instead of architecting a single, theoretical "perfect stack."

Crucially, "crappy" doesn’t mean reckless in production. It means:

- Intentionally small scope.

- Intentionally low ceremony.

- Intentionally optimized for feedback, not prestige.

Safety comes from boundaries and tooling, not paralysis.

The Public Counter: Accountability as Dev Practice

Putilin describes putting a public counter next to his Twitter handle to track his writing output. It’s a social commit log: mildly embarrassing, quietly powerful.

Engineering teams already do this, but often in ways that are either too performative (vanity metrics) or too opaque (nobody can see progress).

A healthy adaptation of the 100-things counter for technical orgs might include:

- A visible tally of postmortems completed (with quality standards, not blame).

- A running count of internal technical notes or ADRs, emphasizing clarity over polish.

- A team goal of “100 small improvements” to build tooling, CI speed, DX, or observability.

The power of the counter is narrative, not surveillance. It tells the team: "We are the kind of people who finish and share things." The things don’t all have to be profound; they just have to be real.

Applying the 100-Things Protocol Across the Stack

For developers, SREs, ML engineers, and tech leaders, here’s how this mindset maps directly onto your day job.

Backend & API engineers:

- Ship 100 PRs that each make one part of the system clearer, safer, or faster.

- Write 100 small integration tests that encode previously tribal knowledge.

SREs / Infrastructure:

- Run 100 micro-improvements to infra-as-code, deploy pipelines, alert routing, documentation.

- Log them. Watch cognitive load and MTTR drop.

Security teams:

- Execute 100 real, documented security fixes or hardening steps.

- Treat each as shipped work, not a backlog forever "under review."

ML / AI teams:

- Run 100 model or prompt experiments, but require each to be written up: metric, change, result.

- Volume plus explicit learning beats "stealth tinkering" every time.

Engineering leaders:

- Encourage 100 observable contributions, not 3 mythical, year-long "moonshots."

- Reward closed loops: decisions made, code merged, docs shipped, incidents analyzed.

The pattern is universal: break ambition into countable, finishable units, expose them to reality, let the compounding happen.

When 100 Is Just the Start

Putilin ends up somewhere subtle but important: by the time he completes the challenge, the counter no longer matters. The skill has taken root; writing is no longer negotiated with himself each time.

That’s the quiet endgame for mature engineering cultures.

- Release rituals become lightweight because trust is earned through repetition.

- Documentation exists because "of course we write it down," not because a process document says so.

- Postmortems are reflexive, not heroic.

The 100-things mindset isn’t about hitting an arbitrary number; it’s about crossing a threshold where output is normal, not aspirational.

If you’re a developer or tech leader, this is the invitation:

Pick one axis that matters — reliability, documentation, tooling, experiments, tiny features — and commit to 100 completed, visible, slightly-better-than-crappy units of work.

Skip the mythic rewrite. Ship the next thing. And then 99 more.

Source: "Do 100 things (5/30)" by Sasha Putilin, Psychotechnology Substack — https://psychotechnology.substack.com/p/do-100-things-530

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion