Unpack the trigonometry-driven illusion that powered classic demos, where textures map onto a virtual cylinder for real-time 3D movement. Modern GPUs breathe new life into this technique, showcasing its enduring simplicity and performance efficiency.

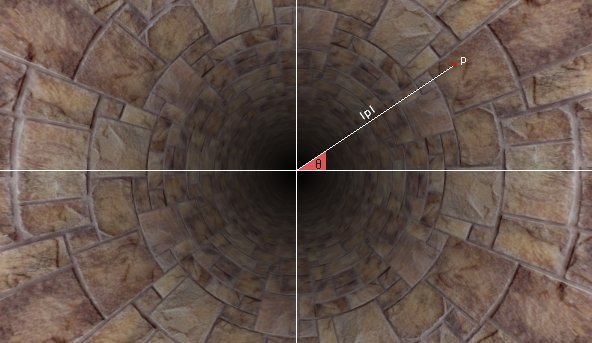

In the golden age of demos, the pseudo-3D tunnel effect captivated audiences with its hypnotic sense of depth and motion. This clever trick, often seen in early computer graphics, relies not on complex 3D engines but on a straightforward mathematical mapping technique. By projecting a texture onto an axis-aligned cylinder and manipulating coordinates, it creates an immersive illusion of movement through space—all with minimal computational overhead.

How the Illusion Works: Trigonometry in Action

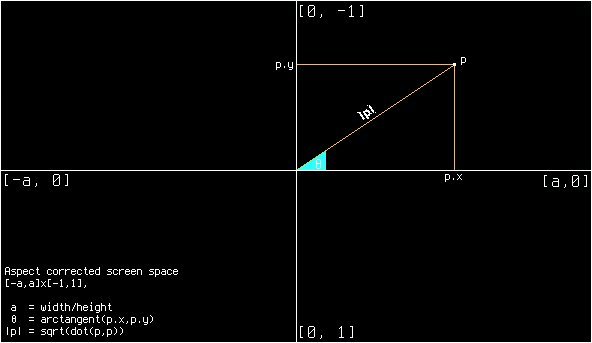

At its core, the algorithm visualizes a texture wrapped around a finite cylinder. Imagine peering through a tunnel: the texture's horizontal (u) coordinate maps to the cylinder's circumference using the spherical theta angle (φ), calculated as atan(p.x, p.y), where p represents normalized screen coordinates. The vertical (v) coordinate corresponds to the reciprocal distance (1 / length(p)) from the origin, simulating perspective as objects appear smaller farther away. This approach transforms 2D screen points into a 3D-like environment using basic trigonometry.

Animation enhances the effect effortlessly. By adding a scrolling offset (s) to the UV coordinates—such as iGlobalTime * vec2(0.1, 1)—the texture moves, creating the sensation of forward motion. Historically, demoscene developers used precomputed lookup tables to optimize this for limited hardware. Today, fragment shaders handle these calculations in real time with negligible cost.

Implementing the Tunnel in GLSL

Below is a concise GLSL fragment shader demonstrating the technique. It accepts screen coordinates, computes the UV mapping, and applies scrolling for animation:

#ifdef GL_ES

precision highp float;

#endif

void main(void)

{

vec2 p = (2. * gl_FragCoord.xy / iResolution.xy - 1.) * vec2(iResolution.x / iResolution.y, 1.);

vec2 t = vec2(atan(p.x, p.y) / 3.1416, 1. / length(p));

vec2 s = iGlobalTime * vec2(.1, 1);

vec2 z = vec2(3, 1);

float m = t.y + .5;

gl_FragColor = vec4(texture2D(iChannel0, t * z + s).xyz / m, 1);

}

Key elements include:

- Normalization:

padjusts for screen aspect ratio. - UV Calculation:

tcombines the angle (scaled by π) and inverse distance. - Animation:

sintroduces time-based scrolling. - Texture Scaling:

zstretches the texture for visual control. - Brightness Adjustment:

mmodulates intensity based on distance.

This shader exemplifies how accessible real-time graphics can be—modern GPUs execute it instantly, eliminating the need for archaic optimizations.

Evolution and Modern Applications

Variations of this base technique add complexity, such as distorting colors or combining multiple passes, as seen in enhanced demos.  illustrates one such iteration, where post-processing amplifies the tunnel's dynamism. For developers, this method remains relevant in retro-game revivals, educational tools for learning shader programming, and performance-critical applications where lightweight rendering is key.

illustrates one such iteration, where post-processing amplifies the tunnel's dynamism. For developers, this method remains relevant in retro-game revivals, educational tools for learning shader programming, and performance-critical applications where lightweight rendering is key.

The pseudo-3D tunnel stands as a testament to elegant problem-solving: transforming simple math into sensory magic. As GPU capabilities grow, rediscovering these classics underscores how foundational principles continue to inspire efficient, creative coding.

Source: 4rknova.com

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion