A new framework treats AI agents as dynamic recipes rather than fixed specialists, enabling runtime specialization that outperforms static approaches on complex benchmarks.

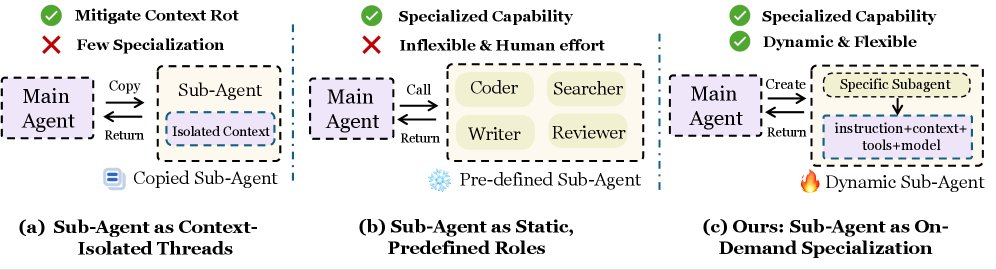

Most AI agent systems today operate under a fundamental constraint: they treat agents as either rigid specialists locked into predetermined roles or as context-isolated threads that lose all accumulated knowledge each time a new agent spawns. This creates a hidden tax on complex problem solving.

Imagine a software development team where every time someone switches tasks, they lose access to what they learned before. The front-end developer writes some code, hands it off to the backend developer, but the backend developer doesn't know about the design constraints the front-end developer discovered. Then the backend developer hands off to QA, and QA starts from scratch. Each handoff loses information.

Alternatively, you could assign the same person to every role, but then they're constantly context-switching and never developing real expertise. That's the trap existing multi-agent systems face.

Researchers have documented this problem across frameworks, recognizing that multi-agent systems struggle with the tension between specialization and coherence. Some attempts at orchestral frameworks for agent orchestration have explored layered approaches, while others have looked at hierarchical structures for multi-agent reasoning, but they still work within this constraint.

The Two Failed Approaches

The first approach treats sub-agents as isolated executors. Each time the system spawns a new agent, it gets only the immediate task. Everything the orchestrator learned is forgotten. This prevents "context rot" (where an agent's context window fills with accumulated, irrelevant details from past steps), but it means every new agent starts cold. If the orchestrator discovered that a user is on macOS or prefers a particular coding style, the next sub-agent never learns it.

The second approach assigns sub-agents static, pre-defined roles. You build a "Code Writer Agent," a "Testing Agent," and a "Documentation Agent," each with its own fixed tools and instructions. This preserves continuity and keeps agents specialized, but it's inflexible by design. What happens when a task needs something your pre-engineered agents can't handle? You're stuck. You'd need to anticipate every possible combination of skills beforehand, which defeats the purpose of using AI agents.

The deeper issue both approaches share is that they answer the question "What can this agent do?" at design time, not at execution time. The system cannot reshape its team composition to match the task at hand.

A Recipe, Not a Machine

AOrchestra begins with a conceptual shift. Instead of thinking of agents as monolithic entities, treat them as recipes. A recipe doesn't describe a machine; it describes how to combine ingredients in a specific way to get a specific result.

Any agent, under this framework, can be described as a 4-tuple:

Instruction is the task-specific goal or prompt. "Parse this JSON file into Python objects" or "Debug why this test is failing." This piece changes most frequently and is the most specific to the immediate problem.

Context is the accumulated state relevant to this particular subtask. If the orchestrator learned that the user's codebase uses type hints, that matters for a code-writing subtask. If the orchestrator knows the user is working in a constrained environment with limited dependencies, that should flow to the next agent. Context connects the dots between steps; it's what prevents each new agent from starting blind.

Tools are the executable capabilities the agent can call. A code interpreter. A file reader. A database query interface. A web browser. Different subtasks need different tools. A code-writing agent might need file system access and a Python interpreter. A research agent might need only a search API. By making tools explicit, the system can grant each agent exactly what it needs, no more, no less.

Model is the language model performing the reasoning. This is where performance-cost trade-offs live. A simple verification task might run on a fast, cheap model. A complex design task might require a more capable model. The system can choose the right tool for the job.

This abstraction is powerful because it's complete and composable. These four components fully specify an agent. By making them explicit, the orchestrator can construct the right specialist for each moment on demand. You don't pre-engineer every possible combination. You assemble them at runtime based on what the task actually requires.

How Orchestration Actually Works

The orchestrator operates in a deliberate loop. When a user gives it a task, the orchestrator doesn't immediately create one large agent to solve it. Instead, it decomposes the problem and spawns specialized agents one at a time.

Here's the decision loop:

First, the orchestrator receives the overall task. "Fix this GitHub issue" or "Answer this question using available tools."

Second, it identifies the immediate subtask. What's the next step? Does the system need to understand the problem context? Read some files? Write code? Run a test? Each of these is a discrete piece of work.

Third, it curates the context dynamically. The orchestrator extracts only the information relevant to this specific subtask from everything it knows. If you mentioned you're using Python 3.11 but the current task is writing JavaScript, that context doesn't travel forward. Keeping context lean means agents spend their tokens on the actual task, not on irrelevant background.

Fourth, it selects the right tools. Based on the subtask, the orchestrator grants the agent access to specific capabilities. Need to execute Python? Grant a code interpreter. Need to search the web? Grant a search API. Need to modify files? Grant file system access. Tools are plugin-and-play; the orchestrator picks and combines them as needed.

Fifth, it chooses the model. Simple tasks get fast, cheap models. Complex reasoning gets capable models. This is where you start making explicit performance-cost trade-offs.

Sixth, the orchestrator instantiates the agent with this specific (Instruction, Context, Tools, Model) tuple and delegates the subtask. The agent runs to completion.

Seventh, results get folded back into the orchestrator's state. What the agent learned becomes context for the next agent.

This loop repeats until the original task is solved.

The elegance lies in the fact that this loop doesn't require extensive pre-engineering. You're not building different agent types for every possible scenario. You're building one flexible orchestrator and one simple abstraction for what an agent is.

Proof: Where This Approach Wins

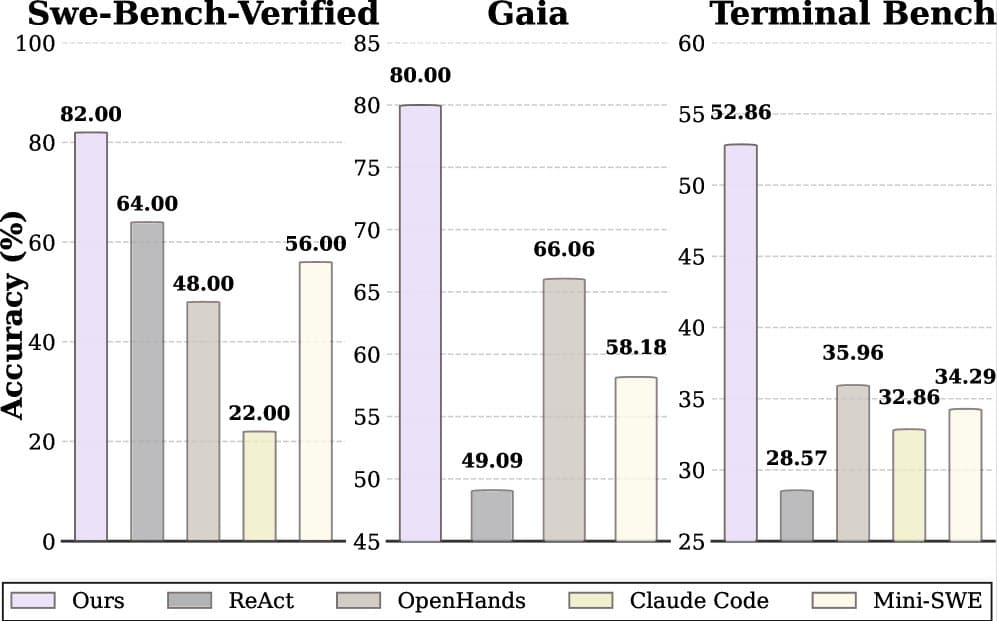

AOrchestra was tested on three challenging benchmarks, each designed to stress-test AI agents on realistic, complex tasks.

GAIA evaluates agents on open-domain reasoning questions. Tasks include "Find the birth date of the person who directed the most Oscar-winning films" or "Calculate the sum of the first 100 prime numbers." These require multi-step reasoning, judgment about when to search versus when to compute, and tool selection.

SWE-Bench-Verified tests agents on real software engineering tasks. Given a GitHub issue in a real repository, can an agent write code that fixes it? These are long-horizon tasks requiring agents to navigate large codebases, understand context across multiple files, and write correct, idiomatic code.

Terminal-Bench tests command-line system administration. Agents must accomplish tasks like file manipulation, log analysis, and system configuration. They require understanding system state, predicting command effects, and composing commands correctly.

AOrchestra achieved a 16.28% relative improvement over the strongest baseline when paired with Gemini-3-Flash, a relatively fast and cost-effective model. This matters because it shows the gains aren't contingent on using expensive, powerful models.

Why does it win? Because dynamic specialization works better than static design. On GAIA, the system spawns a web-search agent when needed, a computation agent when needed, and a reasoning agent when needed. It doesn't try to be everything at once. On SWE-Bench, context flows between agents, so insights about the codebase (the testing framework used, the style conventions) travel to new agents. On Terminal-Bench, each agent gets exactly the system access it needs.

This connects to broader work in hierarchical multi-agent frameworks, where researchers have explored how structure improves multi-agent performance. But AOrchestra's approach is different: rather than imposing structure, it makes structure a runtime decision.

The Performance-Cost Frontier

One of AOrchestra's practical strengths is explicit control over performance-cost trade-offs. Because agents are defined at runtime and models can be selected dynamically, the orchestrator can make cost-aware decisions.

For simple subtasks (confirming a decision, listing files, summarizing a document), use a fast, cheap model. For complex subtasks (designing an algorithm, debugging a subtle bug, architectural decisions), use a more capable model.

This isn't just theoretical; the system approaches what's called a Pareto frontier, where you cannot improve performance without increasing cost.

The frontier means you have choices. If you're cost-constrained (deploying to millions of users), you pick a point further left on the curve, accepting lower accuracy. If you're performance-constrained (a high-stakes application where errors are expensive), you pick further right, spending more per task. The system lets you choose your trade-off rather than forcing one upon you.

Building Systems Differently

AOrchestra suggests a different mental model for how to build complex AI systems. Three shifts stand out.

First, it decouples capability from design time. When you build an agent system today, you make bets about what it will need: "This agent will need a code interpreter, a file reader, and an API client." If you bet wrong, the system is inflexible. AOrchestra defers those decisions to runtime. You don't decide what tools an agent needs until you know what task it's solving. This is lazy evaluation applied to agent design.

Second, it requires less human engineering. Pre-building agents for every possible role or combination of roles is tedious and brittle. It requires perfect foresight. With dynamic instantiation, the system's behavior emerges from a simple abstraction, an orchestrator's decision logic, and the models' capabilities. You build less, but get more flexibility as a result.

Third, it's framework-agnostic. The abstraction is simple enough that any LLM framework can implement it. An OpenAI agent, an Anthropic agent, a local open-source model, all can be plugged in as tools. This is plug-and-play flexibility at the system level.

The underlying principle is that composition scales better than pre-engineering. Rather than trying to anticipate every possible agent configuration, you define primitives (Instruction, Context, Tools, Model) and let their combinations generate possibilities.

For practitioners, this suggests inverting the traditional design pattern. Instead of "make the agent smarter," try "make the orchestrator smarter about which agent to create."

The code is available at https://github.com/FoundationAgents/AOrchestra for anyone wanting to experiment with these ideas.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion