Eva PenzeyMoog's excerpt from 'Design for Safety' outlines a five-step methodology for technologists to proactively address how their products can be weaponized for abuse. Moving beyond the intention to build ethical tools, the Process for Inclusive Safety provides a concrete framework for identifying risks, creating archetypes, and designing solutions that protect vulnerable users.

Antiracist economist Kim Crayton famously stated that "intention without strategy is chaos." In the realm of technology, where the distance between creator and user is vast and the potential for misuse is staggering, this insight cuts to the core of a persistent problem. Many technologists possess the genuine intention to build helpful, safe products, yet they often lack a structured strategy to realize that goal. The gap between wanting to do good and actually producing safe technology is where harm occurs. Eva PenzeyMoog’s excerpt from Design for Safety aims to fill that gap, offering a robust methodology to transform good intentions into a deliberate practice of protection.

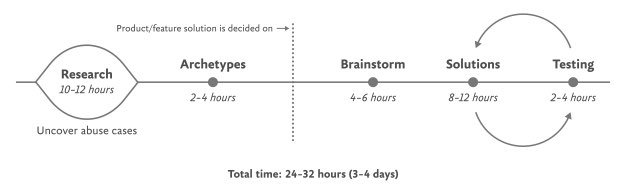

The core of this methodology is the Process for Inclusive Safety, a framework PenzeyMoog developed to integrate safety principles directly into the design workflow. It is not a rigid checklist but a flexible tool meant to be inserted into existing processes. The process is built on a clear triad of goals: identifying ways a product can be used for abuse, designing ways to prevent that abuse, and providing support for vulnerable users to reclaim power and control. It consists of five distinct but interconnected stages.

Step 1: Conduct Research

The foundation of any safety-oriented design is a deep and unflinching understanding of the problem space. This research must be twofold. First, it requires a broad analysis of how similar technologies have already been weaponized. A team building a smart home device, for instance, must investigate the known ways existing devices have been used as tools of domestic abuse. This involves looking beyond the immediate product category to broader issues like data security, algorithmic bias, and online harassment. Academic resources like Google Scholar are invaluable here, providing documented evidence of potential and actual harms.

Second, the research must be specific, focusing on the lived experiences of those most affected. This means speaking with experts and survivors. Before interviewing survivors of trauma, it is crucial to engage with advocates and organizations in the relevant field (e.g., domestic violence hotlines) to build a foundational understanding and avoid causing retraumatization. When interviewing survivors, PenzeyMoog is unequivocal: their knowledge and lived experience must be compensated. Asking survivors to share their trauma for free is exploitative; payment or a donation to a relevant organization is a necessary ethical step. While direct interviews with abusers are generally impractical and unadvisable, understanding their methods is possible through general research into how bad actors weaponize technology and cover their tracks.

Step 2: Create Archetypes

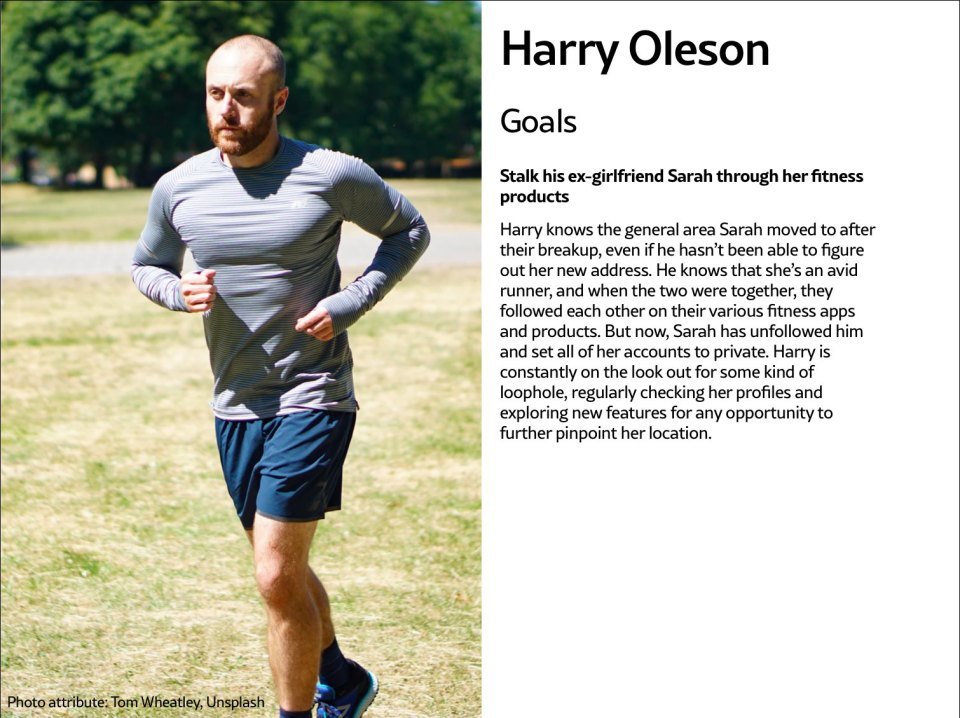

With research in hand, the next step is to synthesize findings into actionable tools: abuser and survivor archetypes. It is critical to distinguish these from standard user personas. Personas are typically based on interviews with real users and are filled with demographic details. Archetypes, conversely, are generalized models based on research into likely safety issues. Just as accessibility design creates archetypes for users with disabilities without needing to have interviewed every user, safety design creates archetypes for potential abusers and victims.

The abuser archetype represents someone who views the product as a tool to perform harm. Their goals are specific: to surveil, control, monitor, or harass. For a fitness app, this might be an ex-partner trying to stalk someone. The survivor archetype is the person being abused with the product. Their goals are the inverse: to prevent abuse, understand if it is happening, stop ongoing abuse, or regain control. A survivor might need to prove abuse they suspect is happening or find out how a stalker is accessing their location data. Creating multiple survivor archetypes to capture different scenarios is encouraged. These archetypes, focused on goals rather than demographics, become the guiding lights for the design phase.

Step 3: Brainstorm Problems

This stage is about exhaustive, creative ideation focused on identifying novel abuse cases—harms specific to the product that were not uncovered in the initial research. The objective is to identify as many potential harms as possible without yet worrying about solutions. PenzeyMoog suggests a time-boxed "Black Mirror" brainstorm, imagining the most dystopian and awful ways the technology could be used for harm. This exercise, while often fun for participants, serves a serious purpose: it pushes the team to think beyond obvious risks. After exploring these wild scenarios, the team should return to more realistic forms of harm. It is impossible to guarantee 100% coverage of every potential harm, but dedicating significant time (at least four hours) and committing to ongoing vigilance after release is the responsible approach.

Step 4: Design Solutions

Armed with a list of potential harms and archetypes defining user goals, the team can move to designing solutions. The strategy here is twofold: prevent the abuser’s goals and support the survivor’s goals. This involves asking critical questions: Can we design the product so the harm cannot happen at all? If not, what roadblocks can we erect? How can we make a victim aware that abuse is occurring? Can we help them understand how to stop it?

Sometimes, this can be proactive. A pregnancy app, for instance, could be designed to allow a user to report an assault, triggering an offer of resources. However, this requires extreme caution. If an abuser monitors a user’s device, any proactive help must be voluntary and designed to keep the user safe within the app, rather than directing them to external sites that could be flagged. The goal is to empower the survivor without increasing their risk.

Step 5: Test for Safety

The final step is rigorous testing from the perspective of the archetypes. This is not usability testing in the traditional sense; it is an adversarial process. The team must try to weaponize the product to achieve the abuser archetype’s goals. For a fitness app with private location settings, this means a tester should attempt every possible method to extract location data from a user who has set their profile to private. If they succeed, the design has failed and must be revised. This may require iterating through steps 4 and 5 multiple times.

Survivor testing focuses on whether the product can effectively provide information and control. For a smart thermostat, this means testing if a user can easily access a log of who changed the temperature and how to revoke another user’s access. PenzeyMoog also advocates for incorporating stress testing, a concept from Design for Real Life by Eric Meyer and Sara Wachter-Boettcher. This involves testing the product with users who are in "stress cases"—anxious, grieving, or overwhelmed—to identify where the design lacks compassion and fails under real-world pressure.

Ultimately, the Process for Inclusive Safety is a call to move beyond the vague aspiration of ethical technology. It provides a concrete, repeatable strategy for building products that are not only functional and profitable but also fundamentally safer for the people who use them.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion