New research reveals that gamers' preferences for inverted controls stem from cognitive processing speeds, not just early gaming habits. Scientists found that mental rotation abilities predict control schemes, with implications for human-machine interfaces in gaming, surgery, and AI. The findings challenge long-held assumptions and could optimize interactions in high-stakes tech environments.

Five years ago, a seemingly niche question—why do some gamers invert their controller axes?—ignited a viral debate that drew over a million readers. At its heart was a split in gaming communities: while most push a joystick down to look down in 3D games, a minority "invert" controls, pulling back to look up like a pilot. This preference, often attributed to early experiences with flight simulators, prompted neuroscientists Dr. Jennifer Corbett and Dr. Jaap Munneke to launch a landmark study during the pandemic. Their findings, published this month, reveal that the real drivers are cognitive processes, reshaping how we design human-machine interfaces.

Which way is up? Gamers' control preferences vary widely, but new research shows it's less about nostalgia and more about brain wiring. (Photograph: Monika Wisniewska/Alamy)

Which way is up? Gamers' control preferences vary widely, but new research shows it's less about nostalgia and more about brain wiring. (Photograph: Monika Wisniewska/Alamy)

The Surprising Path from Gamer Debate to Cognitive Breakthrough

When the UK locked down in 2020, Corbett and Munneke pivoted from lab-based neuroscience to remote experiments, leveraging the controller inversion debate as a perfect test case. They surveyed hundreds of gamers, including machinists, pilots, and surgeons, uncovering a tangle of theories. Many believed their first game—like Microsoft Flight Simulator—locked in their control scheme forever.

{{IMAGE:4}} Early flight simulators were thought to dictate control preferences, but cognitive testing debunked this. (Photograph: Microsoft)

Yet, as Corbett notes: "None of the reasons people gave us actually predicted whether they inverted. We had to dig deeper into the brain's wiring." Through Zoom-based cognitive tests, participants tackled mental rotation tasks (visualizing twisted shapes), perspective-taking exercises, and the "Simon effect" (a conflict where responding to opposite-screen targets slows reaction times). Machine learning then sifted the data, exposing a startling pattern: inversion wasn't about gaming history—it was about cognitive speed.

The Brain's Role: Speed vs. Accuracy in Control Schemes

The study revealed that non-inverters excelled at rapid mental rotation and overcoming the Simon effect, completing tasks faster than inverters. However, inverters were slightly more accurate, suggesting a trade-off between speed and precision. This cognitive profile—not childhood gaming habits—best predicted control preferences. As Corbett explains: "Faster mental rotators were less likely to invert. Those who sometimes switched schemes were the slowest, indicating flexibility comes at a cognitive cost."

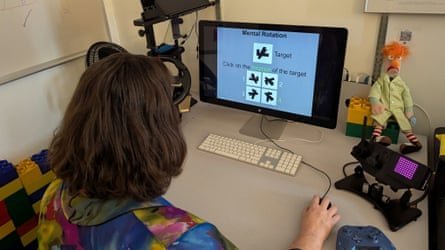

{{IMAGE:5}} Cognitive testing, like this mental rotation experiment, showed that processing speed—not past gaming—shapes control preferences. (Photograph: Jen Corbett)

This reframes long-held gamer lore. Inverters aren't just nostalgic for 1980s flight sims; their brains process 3D space differently. Corbett urges gamers to experiment: "Non-inverters should try inversion—and vice versa. Like left-handed writers forced to use their right hand, sticking to one scheme might limit potential. A few hours of practice could unlock better performance."

Beyond Gaming: A Framework for Human-Machine Teaming

The implications extend far beyond controllers. Corbett and Munneke's framework—now published and cited—could optimize interfaces in laparoscopy, drone operation, and AI collaboration. By tailoring controls to individual cognition, we reduce errors in high-stakes scenarios. Corbett emphasizes: "This isn't just about beating a boss fight. It's about smoother human-AI partnerships, whether you're in surgery or controlling autonomous systems."

As gaming continues to drive interface innovation, this research underscores a universal truth: our interactions with technology are deeply personal, shaped by invisible cognitive currents. For developers, it’s a call to build adaptable systems; for users, a reminder that sometimes, flipping the script—or the stick—might just make everything click.

Source: Adapted from The Guardian article "Why do some gamers invert their controls? Scientists now have answers, but they’re not what you think" (September 18, 2025).

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion