Distributed transactions are essential for maintaining data consistency across microservices, but they come with significant performance and availability trade-offs. This article examines practical approaches to distributed transaction management and their implications for system design.

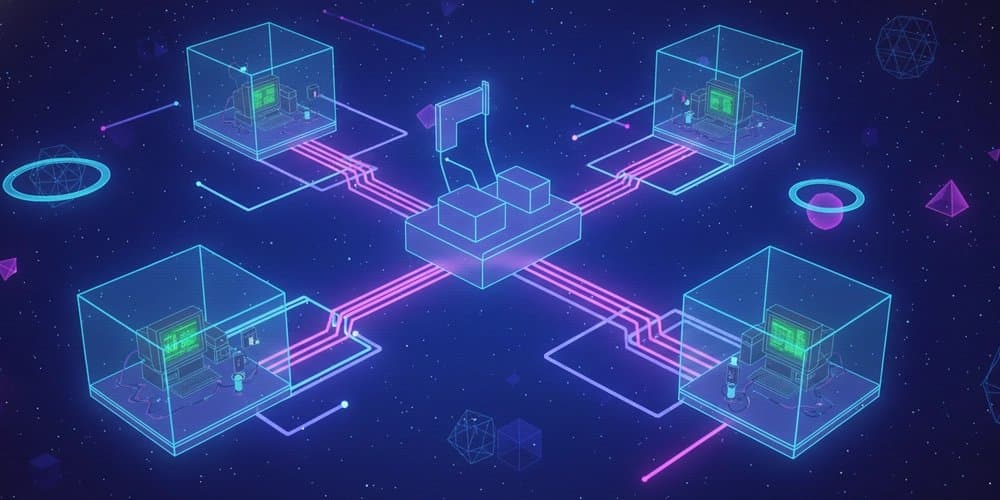

In modern distributed systems, maintaining data consistency across multiple services and databases remains one of the most challenging problems. As organizations decompose monolithic applications into microservices, they often discover that distributed transactions introduce complexity that wasn't apparent in the monolithic world.

The Problem: Consistency Across Service Boundaries

Consider an e-commerce platform where placing an order requires:

- Checking inventory in the inventory service

- Creating an order record in the orders database

- Processing payment in the payment service

- Updating customer points in the loyalty service

In a monolithic application, these operations would typically be wrapped in a database transaction. In a distributed system, each service manages its own database, and traditional ACID transactions become impractical.

The challenge is balancing three competing requirements:

- Consistency: All nodes see the same data simultaneously

- Availability: Every request receives a response (without guarantee it's the most recent)

- Partition tolerance: The system continues operating despite network failures

According to the CAP theorem, a distributed system can only guarantee two of these three properties during a network partition. This fundamental constraint shapes our approach to distributed transactions.

Solution Approaches

Two-Phase Commit (2PC)

The traditional approach to distributed transactions is the Two-Phase Commit protocol, which extends ACID transactions across multiple resources.

Phase 1 (Prepare):

- The coordinator asks all participants to prepare to commit

- Each participant locks resources and writes to its transaction log

- Participants respond with "prepared" or "abort"

Phase 2 (Commit/Rollback):

- If all participants respond "prepared", the coordinator sends "commit"

- If any participant responds "abort", the coordinator sends "rollback"

- Participants release locks after completing the operation

While 2PC provides strong consistency, it comes with significant drawbacks:

- Synchronous blocking: Participants hold locks until all nodes respond

- Coordinator single point of failure: If the coordinator fails during Phase 2, the system may be blocked indefinitely

- Performance overhead: Multiple round-trips between coordinator and participants

- Limited scalability: As the number of participants increases, the probability of failure rises

Despite these limitations, 2PC remains appropriate for:

- Critical business operations where consistency is non-negotiable

- Systems with a small number of participants

- Environments where network partitions are rare

Saga Pattern

For systems where availability and partition tolerance are prioritized over strong consistency, the Saga pattern offers an alternative approach.

A Saga is a sequence of local transactions. If one transaction fails, the saga executes compensating transactions in reverse order to undo the previous transactions.

There are two implementations of the Saga pattern:

Chore-based Saga:

- Each service publishes events upon successful completion

- Other services subscribe to these events and trigger their transactions

- Compensating transactions are triggered by failure events

Orchestration-based Saga:

- A central orchestrator coordinates the sequence of transactions

- The orchestrator knows the entire workflow and invokes services

- The orchestrator initiates compensating transactions when failures occur

The Saga pattern provides:

- High availability: Services remain operational even if others fail

- Eventual consistency: The system reaches a consistent state eventually

- Resilience to network partitions: Failed transactions can be retried or compensated

However, Sagas introduce:

- Increased complexity in compensating transaction design

- Risk of inconsistent states during execution

- Challenges in maintaining data across service boundaries

Event Sourcing and CQRS

For systems requiring high consistency guarantees without the blocking nature of 2PC, event sourcing combined with CQRS (Command Query Responsibility Segregation) offers a powerful alternative.

In this approach:

- All changes to application state are stored as a sequence of events

- The current state is derived by replaying these events

- Commands modify the state by creating new events

- Queries read from a separate, optimized data model

This pattern provides:

- Strong consistency through event ordering

- Full audit trail of all state changes

- Improved performance through separation of read and write models

- Enhanced resilience by storing events immutably

The trade-offs include:

- Increased complexity in system design

- Steeper learning curve for development teams

- Potential performance challenges during event replay

Practical Considerations

When designing distributed transaction strategies, several practical factors influence the decision:

Latency Sensitivity

- Systems requiring low latency may favor eventual consistency models

- Batch processing systems can better tolerate the overhead of 2PC

Data Criticality

- Financial systems typically require strong consistency

- User preference data may tolerate eventual consistency

Failure Scenarios

- Consider the impact of inconsistent states

- Design compensating actions that can safely undo partial operations

Monitoring and Observability

- Distributed transactions require enhanced monitoring

- Implement comprehensive tracing across service boundaries

Implementation Patterns

Several implementation patterns have emerged for distributed transactions in practice:

Outbox Pattern The outbox pattern ensures reliable delivery of events by storing them in the same database as the source data. When a transaction commits, both the data change and the event are persisted atomically. A separate process then polls the outbox table and publishes events to message brokers.

This pattern provides:

- Exactly-once event delivery semantics

- Protection against message loss during failures

- Simplified error handling through database transactions

Idempotency Keys For systems that may retry operations due to failures, idempotency keys ensure that duplicate requests don't cause unintended side effects. Each request includes a unique identifier, and the system tracks processed IDs to avoid duplicate processing.

This approach is particularly valuable for:

- Payment processing systems

- Order creation workflows

- Any operation that shouldn't be repeated

Distributed Locking For operations requiring exclusive access to resources across services, distributed locking mechanisms like Redlock provide coordination without centralization. These algorithms use multiple independent resources to prevent deadlocks and ensure safety.

Trade-offs in Practice

The choice of distributed transaction strategy involves balancing multiple factors:

Consistency vs. Availability

- Strong consistency models like 2PC reduce availability during partitions

- Eventual consistency models maintain availability but risk stale data

Complexity vs. Reliability

- Simpler approaches may be easier to implement but harder to maintain

- Complex patterns like event sourcing provide better resilience but require expertise

Performance vs. Correctness

- High-performance systems often prioritize availability over consistency

- Critical systems may sacrifice performance for stronger guarantees

The appropriate choice depends on specific business requirements, not technical preferences alone. Systems handling financial transactions have different requirements than social media feeds or recommendation engines.

Emerging Approaches

New approaches continue to emerge in the distributed transactions space:

Deterministic Transactions Some systems use deterministic algorithms to ensure that all nodes reach the same state without coordination. These approaches work well for specific use cases but don't generalize to all applications.

Conflict-free Replicated Data Types (CRDTs) CRDTs are data structures that can be replicated across multiple nodes and updated concurrently without coordination. They guarantee eventual consistency and are particularly useful for collaborative applications.

Blockchain-inspired Approaches Some systems are applying blockchain concepts like consensus algorithms to traditional distributed systems problems. These approaches provide strong guarantees but often at significant performance cost.

Conclusion

Distributed transactions represent one of the most challenging aspects of modern system design. There is no one-size-fits-all solution—each approach involves trade-offs between consistency, availability, and partition tolerance.

The most effective systems:

- Clearly define their consistency requirements

- Choose appropriate transaction patterns for different use cases

- Implement comprehensive monitoring and observability

- Design for failure from the beginning

As distributed systems continue to evolve, so too will our approaches to managing consistency across service boundaries. The key is understanding these trade-offs and making informed decisions based on specific business requirements rather than technical preferences alone.

This article has examined the fundamental challenges of distributed transactions and the practical approaches available to address them. Each solution comes with its own set of trade-offs, and the most effective systems are those that thoughtfully apply these patterns based on their specific requirements and constraints.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion