A mathematical exploration of the Chowla conjecture on cosine series minima, combining theoretical analysis with computational experiments to visualize and understand the behavior of these complex trigonometric sums.

The Chowla cosine conjecture presents a fascinating problem in number theory that bridges pure mathematics with computational experimentation. At its core, the conjecture concerns the minimum value of a cosine series where the sum consists of terms of the form cos(kx) for k belonging to some set A with n elements. While the maximum value of such a sum is trivially n (achieved when x = 0), the minimum value remains an open question that has intrigued mathematicians for decades.

The Conjecture and Its Significance

The Chowla conjecture posits that for sufficiently large n, the minimum value of f(x) = Σ cos(kx) should be less than −√n. This might seem modest at first glance, but the best proven results to date fall far short of this bound, making it a tantalizing target for mathematical research. The conjecture touches on deep questions about the distribution of trigonometric sums and their extremal properties.

Initial Computational Explorations

When first approaching this problem computationally, one natural instinct is to select interesting sets A. The author initially chose A to be the first n primes, which led to an unexpected result. Since all primes except 2 are odd, and cos(kπ) = −1 for odd k, the minimum consistently occurred near x = π and was approximately −n. This behavior, while mathematically valid, proved less interesting for exploring the conjecture because it didn't approach the −√n bound.

A visualization of this phenomenon with primes less than 100 reveals a function with a clear minimum near π, but this minimum is far more negative than the conjecture predicts for interesting cases. The plot demonstrates how the dominance of odd frequencies creates this behavior, with the single even prime (2) being insufficient to create the mixing of phases that would lead to more complex behavior.

Finding More Interesting Examples

The key to making the Chowla conjecture computationally interesting lies in selecting sets A that contain a mix of even and odd numbers. This ensures that the cosine terms don't all align destructively at the same points, creating the rich interference patterns that the conjecture predicts.

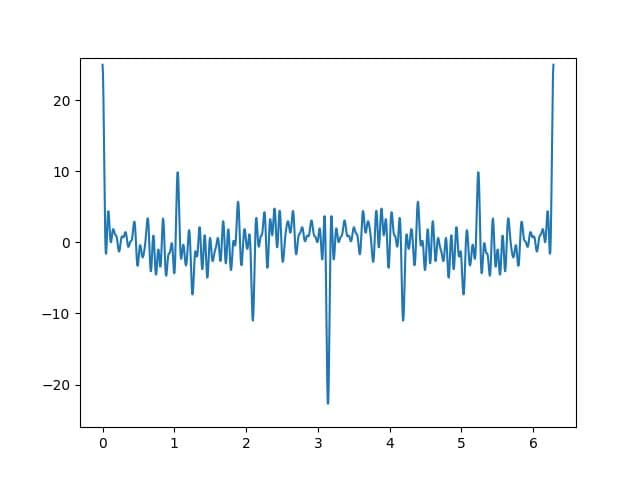

A more compelling example uses a random selection of 25 points between 1 and 100. This creates a function with multiple local minima and a global minimum that appears to be much closer to the −√n bound. The computational approach reveals the complexity of these functions, with numerous local minima that make direct minimization challenging.

Computational Challenges and Solutions

The computational exploration of the Chowla conjecture reveals significant challenges. Direct minimization software proves impractical due to the abundance of local minima in these functions. The landscape is rugged, with many points that appear to be minima when examined locally but aren't the global minimum.

For small values of n and modest values of the elements in A, one can use visualization to identify approximate regions where the minimum occurs, then apply numerical methods to refine the result. However, this approach doesn't scale well to larger problems.

A more sophisticated approach involves finding all zeros of the derivative of f(x). Since the derivative is a sum of sines with integer frequencies, it can be transformed into a polynomial problem. By expressing the derivative as a polynomial in z = exp(ix), one can leverage polynomial root-finding algorithms to locate all critical points. The global minimum will be among these critical points.

This transformation is elegant: the derivative becomes a Laurent polynomial in z and 1/z, which can be converted to an ordinary polynomial of degree 2n by multiplying by z^(2n). The QR algorithm, previously discussed in related contexts, becomes applicable for finding all roots of this polynomial, providing a complete catalog of critical points.

Mathematical Insights from Computation

The computational experiments provide valuable insights into the structure of these cosine sums. The contrast between the prime-based example and the random selection demonstrates how the parity distribution of the frequencies fundamentally affects the function's behavior. When frequencies are predominantly odd, the function exhibits simpler, more predictable behavior. When frequencies are mixed, the function becomes more complex and potentially more aligned with the Chowla conjecture's predictions.

The observation that f(π) = 2 − n for the set of first n primes (since one term equals 1 and n − 1 terms equal −1) provides a concrete example of how specific choices of A lead to exact results. For n ≥ 4, this appears to be the minimum, occurring exactly at π rather than merely near it.

The Path Forward

The combination of theoretical analysis and computational experimentation offers a promising approach to understanding the Chowla conjecture. While the conjecture remains unproven, computational evidence can guide intuition about which types of sets A are most likely to exhibit the conjectured behavior. The polynomial transformation of the derivative problem provides a scalable computational method that could be applied to larger instances, potentially revealing patterns that might inform theoretical approaches.

The Chowla cosine conjecture thus serves as an excellent example of how computational mathematics can complement theoretical work, providing concrete examples, visualizations, and numerical evidence that help mathematicians form and test hypotheses about abstract mathematical structures. As computational power increases and algorithms improve, the gap between what we can prove theoretically and what we can observe computationally may continue to narrow, potentially leading to new insights into this and similar problems in analytic number theory.

{{IMAGE:1}}

The visualization of cosine sums with different frequency sets demonstrates how computational tools can make abstract mathematical conjectures more tangible, revealing the rich structure hidden within seemingly simple trigonometric expressions.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion