A deep dive into Python's bytecode reveals why list comprehensions behaved differently across versions 3.10 and 3.12. Discover how CPython's shift from hidden functions to inlined execution resolves scoping mysteries and impacts your code's behavior.

For years, Python developers encountered subtle scoping quirks with list comprehensions—until Python 3.12 changed everything. A recent analysis of CPython's bytecode reveals the dramatic evolution under the hood, explaining why identical code behaves differently across versions.

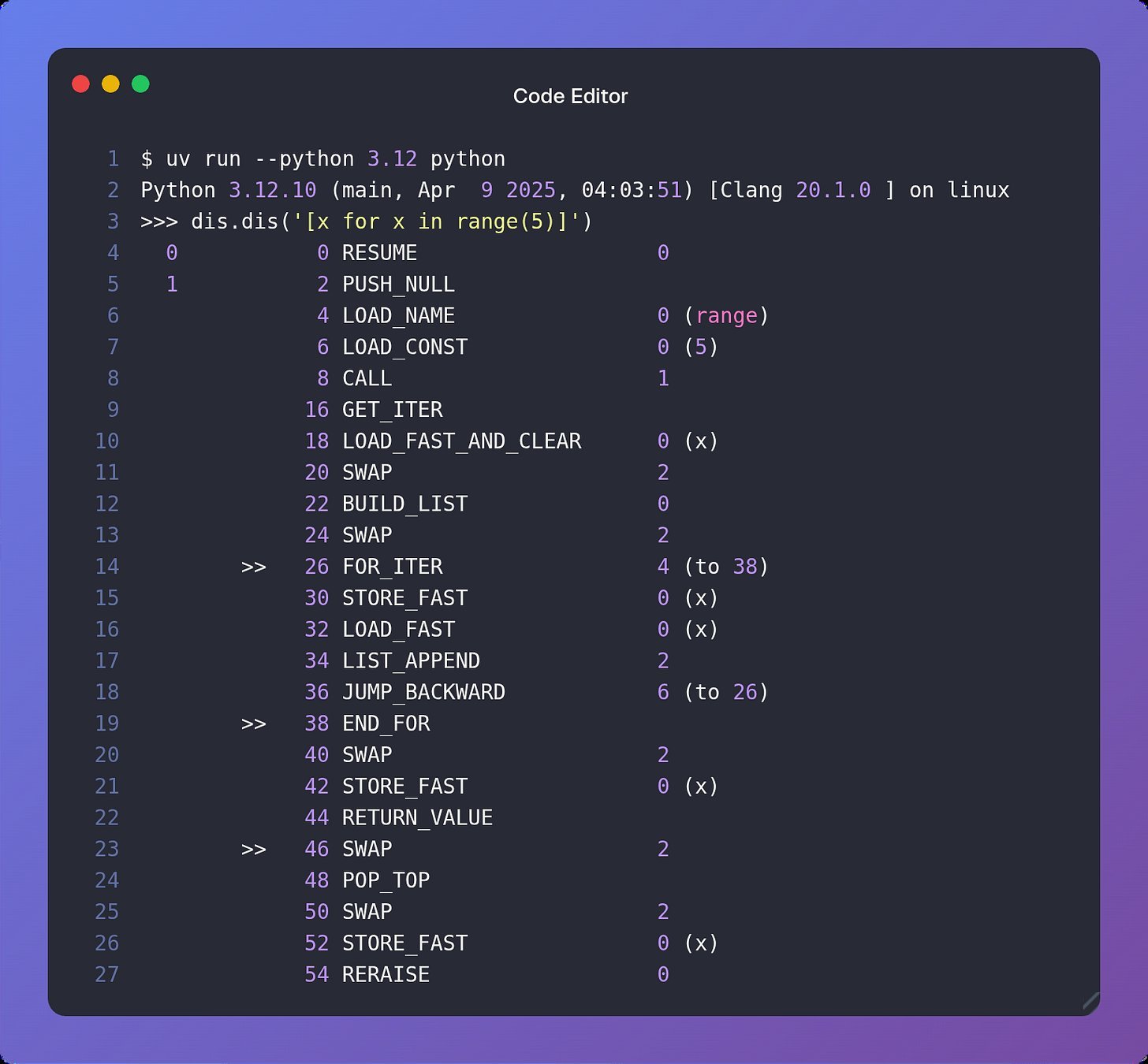

The Scoping Mystery

The puzzle began with this code snippet:

(lambda: [exec('river*single_drop') for single_drop in [1]])()

In Python 3.10, it throws a NameError claiming river is undefined. In 3.12, it runs without issue. The culprit? How list comprehensions handle scope.

Bytecode Forensics: Python 3.10's Hidden Function

Using Python's dis module, we see 3.10 compiles list comprehensions into separate functions:

# Python 3.10: [x for x in range(5)]

0 LOAD_CONST 0 (<code object <listcomp>>)

4 MAKE_FUNCTION 0 # Creates hidden function

...

14 CALL_FUNCTION 1 # Executes it

This hidden function creates an isolated scope. Variables like river in outer scopes become inaccessible, triggering NameError when using exec() inside the comprehension.

Disassembly showing hidden function creation in Python 3.10 (Credit: Python Koans)

Disassembly showing hidden function creation in Python 3.10 (Credit: Python Koans)

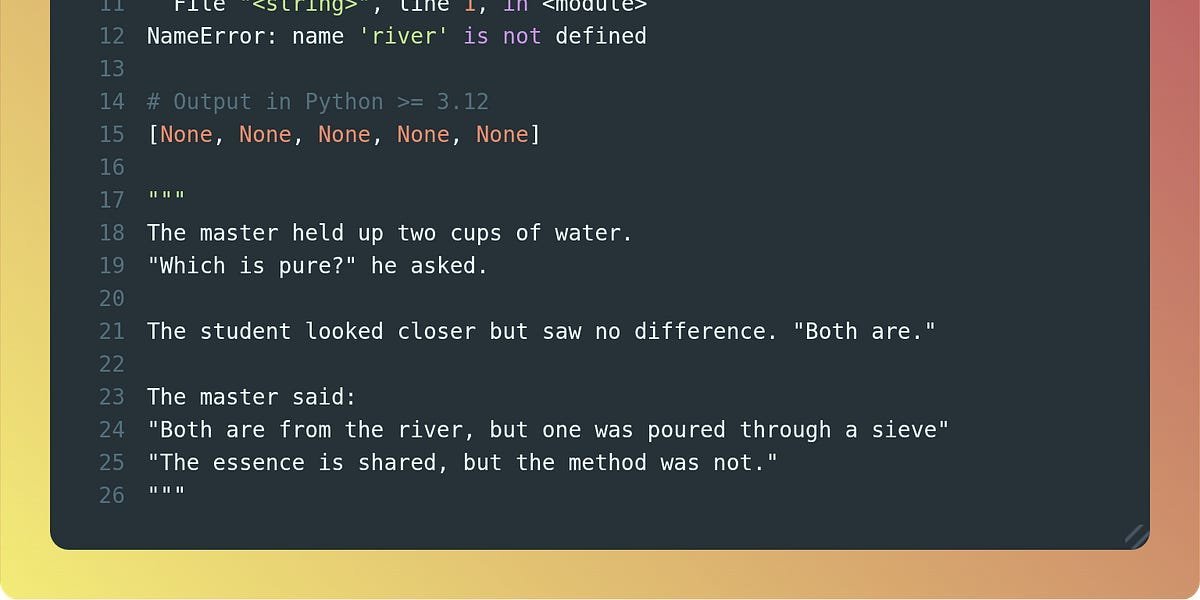

Python 3.12's Inlined Revolution

PEP 709 redesigned comprehensions as inline operations:

# Python 3.12 equivalent

18 LOAD_FAST_AND_CLEAR 0 (x) # Saves outer 'x'

20 SWAP

22 BUILD_LIST 0

...

40 STORE_FAST 0 (x) # Restores outer 'x'

Key changes:

- No hidden function frames

LOAD_FAST_AND_CLEARtemporarily shields outer variables- All operations execute in the current stack frame

Why the Koan Works Now

With inlining:

- The comprehension shares the lambda's scope

exec()accessesriverdirectly- No

NameErroroccurs

The fix for 3.10? Explicitly pass variables to exec:

(lambda: [exec('river*single_drop', {}, {'river': river}) for ...])()

The Performance Ripple Effect

Beyond scoping, inlining offers:

- 35% speed boost for some comprehensions (per PEP 709)

- Reduced memory overhead from fewer function frames

- Cleaner stack traces without

<listcomp>intermediates

Bytecode comparison showing inlined instructions in Python 3.12 (Credit: Python Koans)

Bytecode comparison showing inlined instructions in Python 3.12 (Credit: Python Koans)

Why This Matters

This change exemplifies Python's evolution toward greater transparency and performance. Where hidden abstractions once caused head-scratching errors, inlining provides predictable behavior—proving that even foundational features mature. For developers, it’s a reminder: understanding bytecode isn’t just for compiler writers. When your code acts mysteriously, sometimes the deepest answers live in the stack.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion