In the underground bulletin board systems of the 1990s, an ANSI artist known as Eerie created 'Inspector Dangerfuck'—a character later mislabeled as the 'first internet comic.' This deep dive explores Eerie's experimental animations, the technical constraints of serializing ASCII narratives, and why these artifacts matter to digital art history.

In 1994, a Quebec teenager operating under the handle "Eerie" designed a gray-skinned, yellow-haired character named Inspector Dangerfuck using ANSI art—a digital medium built from text characters and color codes. T Campbell’s 2006 book A History of Webcomics erroneously declared it "the first known comic on the Internet," a claim repeated for decades without verification. Now, original research reveals a more nuanced story: one of artistic hustle, technical ingenuity, and a pre-web experiment that foreshadowed digital storytelling’s challenges.

The Lonely Genesis of a Digital Artist

Eerie (who requested anonymity) described his early 1990s as a period of isolation in his parents’ basement. Equipped with a 300-baud modem, he found community in Quebec’s French-language bulletin board systems (BBS). Initially focused on programming—he developed shareware utilities and e-magazines—he shifted to ANSI art in 1993. His style stood out: loose, cartoony, and influenced by Belgian bandes dessinées like Spirou rather than the era’s dominant Image Comics aesthetics.

{{IMAGE:4}} Eerie’s art diverged from mainstream ANSI trends, incorporating French comic influences like Pévé’s work in "Spirou."

"I adapted my style to fit the scene, even though superheroes felt foreign," Eerie recalled. His early pieces, such as "DISCIPLE.ANS" (June 1993), featured elastic figures and gray skin—unlike the hyper-muscular, shadow-heavy norms of groups like iCE. Reception was mixed; the underground ANSI scene prized technical polish, and Eerie’s work was deemed "all over the place" by peers.

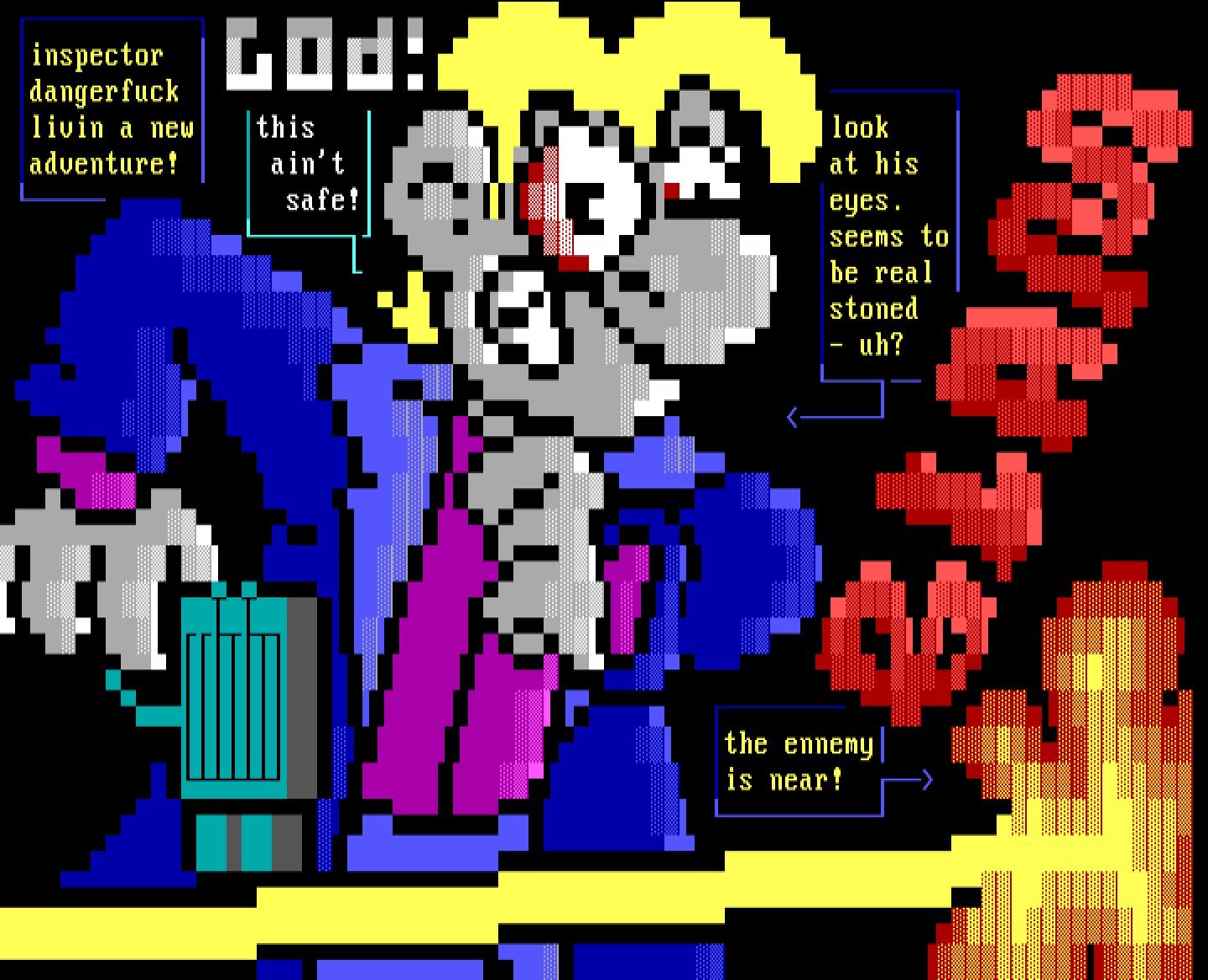

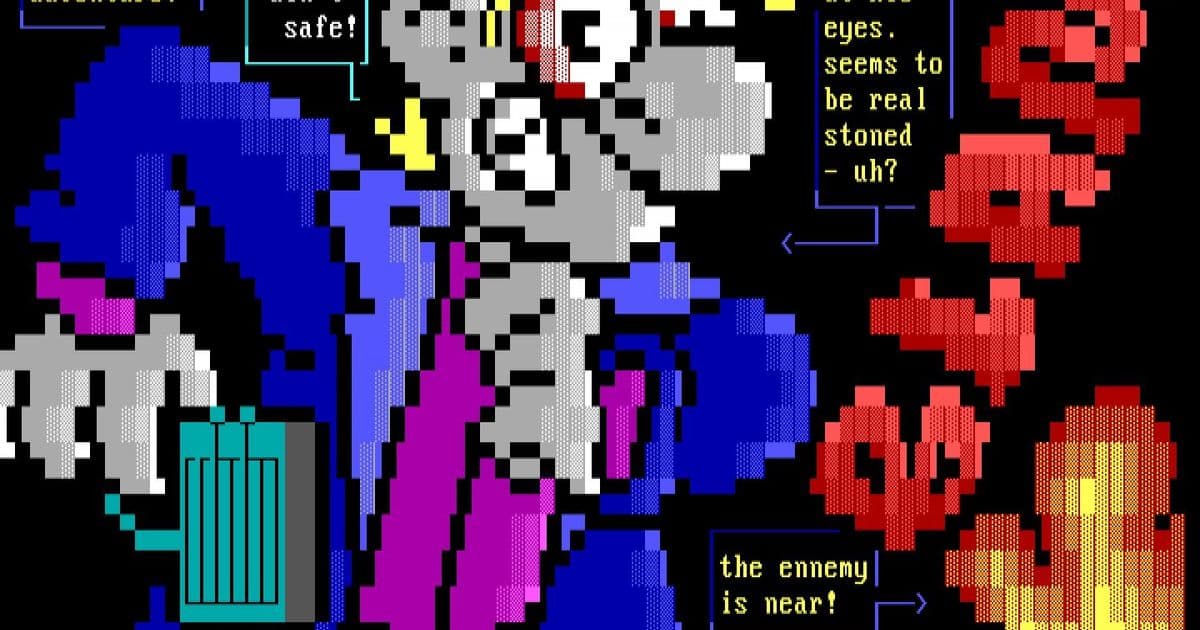

Inspector Dangerfuck: ANSI Art as Proto-Comic

In mid-1994, Eerie joined the short-lived artgroup Imperial and debuted Inspector Dangerfuck. Two releases that July introduced the character through static portraits with meta-commentary (e.g., "Look at his eyes. Seems to be real stoned, uh?"). True innovation followed in August with "EE-NP1.IMP"—a 300-row vertical comic. Using DOS tools like TheDraw (limited to 100 rows per file), Eerie stitched together panels showing the inspector encountering Professor Baldhead. Though Eerie dismisses the art ("not very good"), its deliberate sequence of images and dialogue balloons meets Scott McCloud’s definition of comics.

{{IMAGE:5}} Eerie’s "DISCIPLE.ANS" (1993) showcased his early cartoony style years before Inspector Dangerfuck.

That same month, he released "EE-WOWM1.EXE," a semi-animated demo where users interacted with a bank robbery plot. A September follow-up, "Inspector Dangerfuck vs. Dr. Silly," added parallax effects and scene-specific jokes (e.g., "HARD -> Hot Ansi Rippers Dammit"). Yet serialization faltered; Eerie abandoned the character after joining the elite group ACiD in 1995, citing ANSI’s "ridiculous" effort-to-reward ratio for comics.

Why ANSI Comics Were a Dead End

Eerie rejects the idea that his work pioneered webcomics: "BBSes were online, but not the web. Distribution relied on fragmented art packs or BBS door displays—no serialization framework." He argues precursors were print zines, not ANSI: "EE-NP1.IMP was a dead end." Indeed, BBS comics faced three unsolvable constraints:

- Technical Limits: No in-browser viewing; users downloaded ZIPs and DOS viewers.

- Fragmented Distribution: No centralized platforms—only art packs from shifting collectives.

- Creator Burden: Drawing comics character-by-character in ANSI editors was labor-intensive.

Still, Eerie’s output—including his noirish Noise comics—highlighted early attempts at digital narrative. As historian Rowan Lipkovits noted, he once released "over thirty screens in a month," embodying the scene’s relentless creativity.

The Bigger Picture: Digital Archaeology Matters

Inspector Dangerfuck wasn’t the "first internet comic," but it exemplifies how pre-web communities wrestled with constraints that still echo today: scalable distribution, format accessibility, and creator sustainability. While no direct lineage links ANSI art to modern webcomics, projects like Eerie’s underscore a recurring truth: innovation often blooms in the margins, fueled by isolation and sheer will. As we preserve these digital artifacts, they remind us that every pixelated character holds a story—not just of art, but of the humans coding their way out of loneliness.

Source: Break Into Chat by Josh Renaud (December 31, 2025)

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion