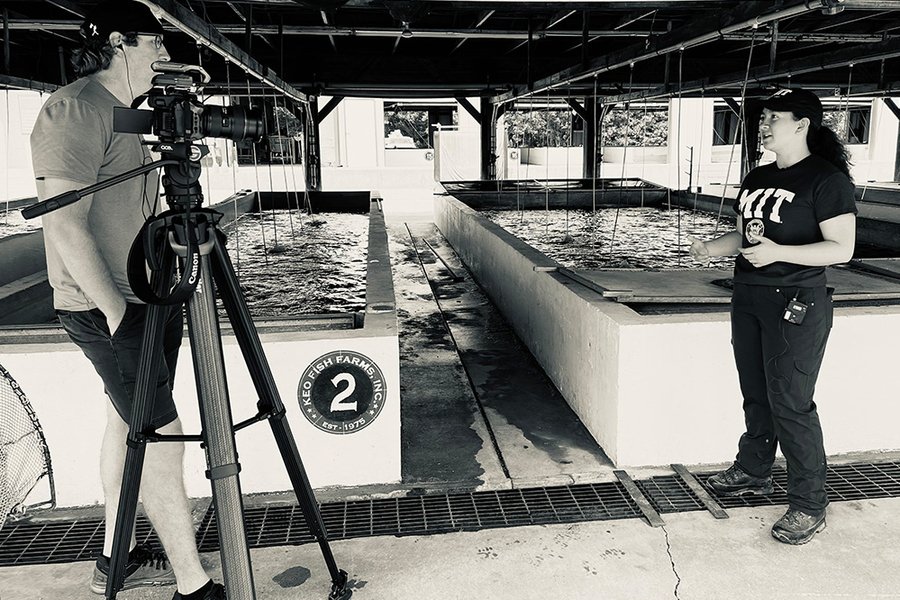

MIT student Kiyoko Hayano collaborates with Arkansas's Keo Fish Farms through MIT D-Lab to develop low-cost water filtration systems addressing iron contamination—a project demonstrating how academic-community partnerships can advance sustainable aquaculture.

In commercial aquaculture, water quality directly determines survival rates, operational costs, and environmental impact. At Keo Fish Farms in Arkansas—a facility producing approximately 150 million fish annually for domestic and international markets—elevated iron levels in groundwater have caused significant fish mortality during peak summer conditions. This challenge became the focus of a collaboration between the farm and MIT D-Lab, spearheaded by mechanical engineering student Kiyoko Hayano. Their work exemplifies how university-community partnerships can develop scalable solutions for regenerative aquaculture systems.

The Water Quality Challenge

Keo Fish Farms raises temperature-sensitive species like hybrid striped bass and triploid grass carp in groundwater-fed holding vats. Iron occurs naturally in the region's geology but concentrates unpredictably in well water due to seasonal aquifer fluctuations. When dissolved iron oxidizes, it forms particulates that clog fish gills and reduce oxygen absorption. Traditional remediation methods like chemical oxidants or ion exchange were cost-prohibitive for the farm's operational scale and conflicted with sustainability goals. "The constraints were multidimensional," explains Hayano. "We needed solutions adaptable to variable iron concentrations, feasible within harvest labor cycles, and aligned with regenerative principles—all while keeping capital costs manageable."

Engineering a Regenerative Approach

Hayano's methodology through MIT D-Lab followed a co-creative framework: understanding on-ground constraints before proposing technologies. Her assessment included:

- System Analysis: Mapping water intake infrastructure, well depths, and geological iron deposition patterns

- Filtration Prototyping: Testing three low-cost approaches:

- Aeration: Oxygenating water to accelerate iron oxidation for easier mechanical filtration

- Sedimentation: Using gravity-based settling tanks to remove oxidized particles

- Biochar Media: Developing filters from pyrolyzed rice hulls (a local agricultural waste product) to bind iron ions

The biochar solution showed particular promise. Rice hulls—abundant in Arkansas's rice-farming regions—undergo pyrolysis to create porous carbon structures that adsorb contaminants. Unlike synthetic resins, spent biochar can be reused as soil amendment, closing nutrient loops. Hayano modeled flow rates, contact time, and iron-binding capacity to design scalable filter units. "Biochar's advantage is dual function," she notes. "It treats water while creating a secondary product for land restoration—a core regenerative principle."

Policy and Infrastructure Synergies

This project intersects multiple national priorities. The USDA promotes conservation practices in aquaculture; the EPA regulates groundwater contaminants; and the Department of Energy funds renewable integration in agriculture. Hayano's work demonstrated how iron filtration could integrate with broader regenerative systems:

- Solar-powered aeration to reduce energy costs

- Nutrient recovery from sludge for fertilizer

- Biochar production from waste biomass

Lieutenant Governor Leslie Rutledge visited Keo Farms during the project, highlighting state-level interest. "Such collaborations show how engineering innovation strengthens rural economies," Rutledge observed. Federal agencies increasingly recognize aquaculture's role in food security, with NSF and DoE grants targeting sustainable water infrastructure.

Limitations and Scaling Challenges

While promising, the approach faces hurdles:

- Seasonal Variability: Iron concentrations fluctuate with rainfall and groundwater recharge, requiring adaptable filtration thresholds

- Biochar Consistency: Non-industrial biochar production yields variable pore structures, affecting adsorption reliability

- Economic Viability: Small farms lack capital for system overhauls; modular, phased installations are essential

Keo Farms aims to become a regenerative showcase, but scaling requires policy support. MIT D-Lab's Kendra Leith emphasizes: "Academic partnerships de-risk innovation for farmers. Federal programs should fund such collaborations directly—not just lab research."

The Road Ahead

Hayano's project created a blueprint for regenerative aquaculture: combining appropriate technology, waste valorization, and closed-loop design. For universities, it validates experiential learning in domestic food systems. For engineers, it proves that rural challenges offer complex, impactful problems. "This reshaped my view of mechanical engineering," Hayano reflects. "It's not just about optimizing machines—it's about designing systems that serve communities and ecosystems."

As climate change stresses water resources, such collaborations will grow crucial. The Keo Farms model—blending academic rigor, community insight, and regenerative design—offers a template for sustainable protein production nationwide. Future work includes automating filtration monitoring and integrating solar thermal for biochar production, advancing both resilience and affordability.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion