What began as a solution to the artificial look of TRON's CGI became one of computer graphics' most influential algorithms. We dissect Perlin noise—Ken Perlin's Academy Award-winning technique—that enables realistic procedural textures, terrains, and animations through elegant mathematical chaos. Discover how this 1980s innovation still powers modern generative AI and game engines.

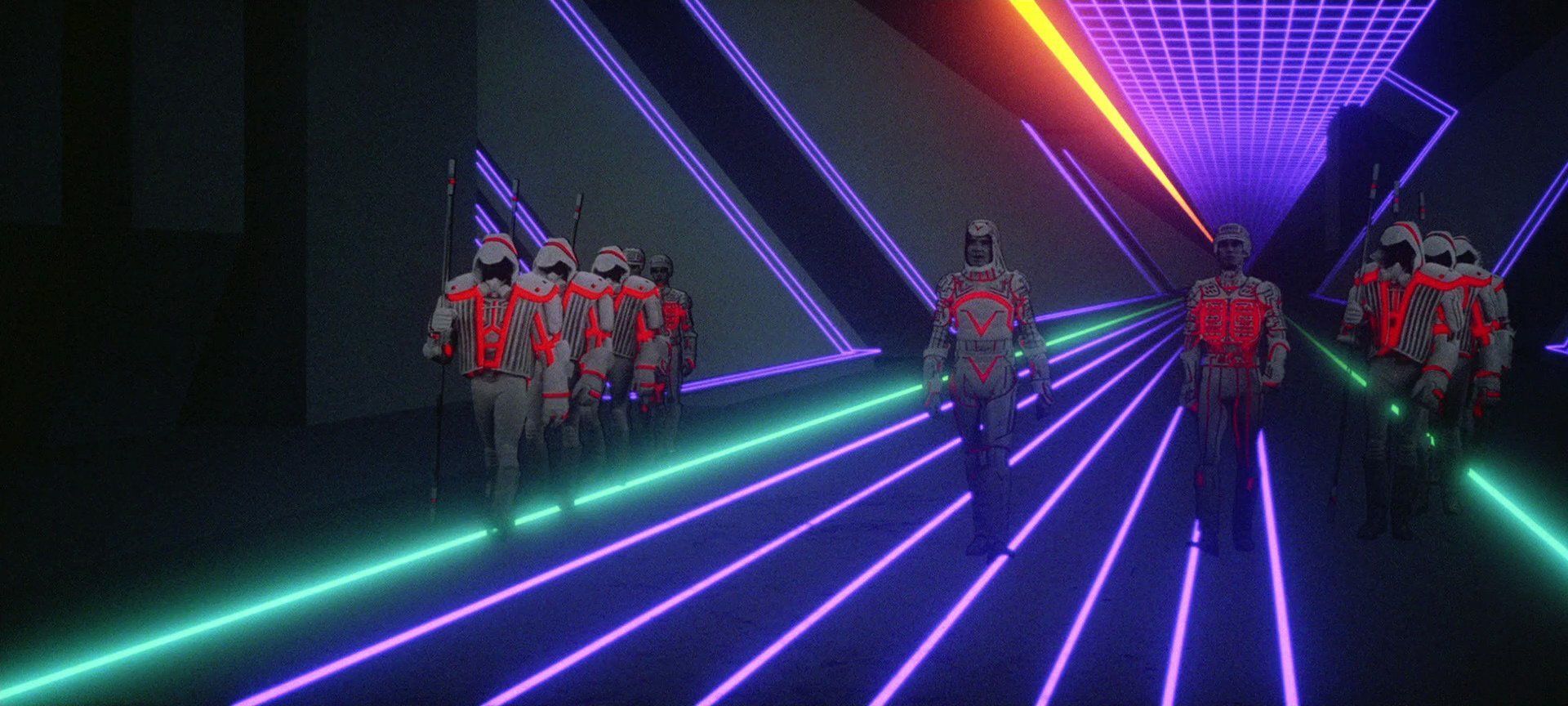

When TRON dazzled audiences in 1982 as the first film with extensive CGI, its creators battled severe technical constraints: 2MB memory, 330MB storage, and computers that could only render still images. Teams painstakingly captured individual frames with motion picture cameras—a process Ken Perlin, then a researcher at Mathematical Applications Group, found artistically limiting. The resulting visuals, while groundbreaking, suffered from a sterile, "machine-like" quality. This frustration ignited Perlin's quest for organic digital textures, culminating in an algorithm that would earn him an Academy Award and transform computer graphics: Perlin noise.

The Mathematics of Organic Imperfection

Perlin rejected conventional polygon-based approaches, conceiving textures as volumes rather than flat surfaces. His breakthrough was using controllable noise to fill these volumes—specifically noise with four critical properties:

1. SMOOTH: Nearby inputs yield similar outputs

2. CONTINUOUS: No sudden jumps or breaks

3. DETERMINISTIC: Same input → same output

4. BOUNDED: Predictable output range

This wasn't random static but mathematically structured variation. Perlin achieved it through gradient vectors and interpolation:

- Grid Creation: Map input coordinates (e.g., pixel positions) to a grid

- Gradient Assignment: Assign each grid corner a consistent vector (e.g., ↗️↖️↙️↘️) using a permutation table

- Dot Products: Calculate influence vectors between grid points and input coordinates

- Faded Interpolation: Blend corner values using a smoothing curve to avoid mechanical transitions

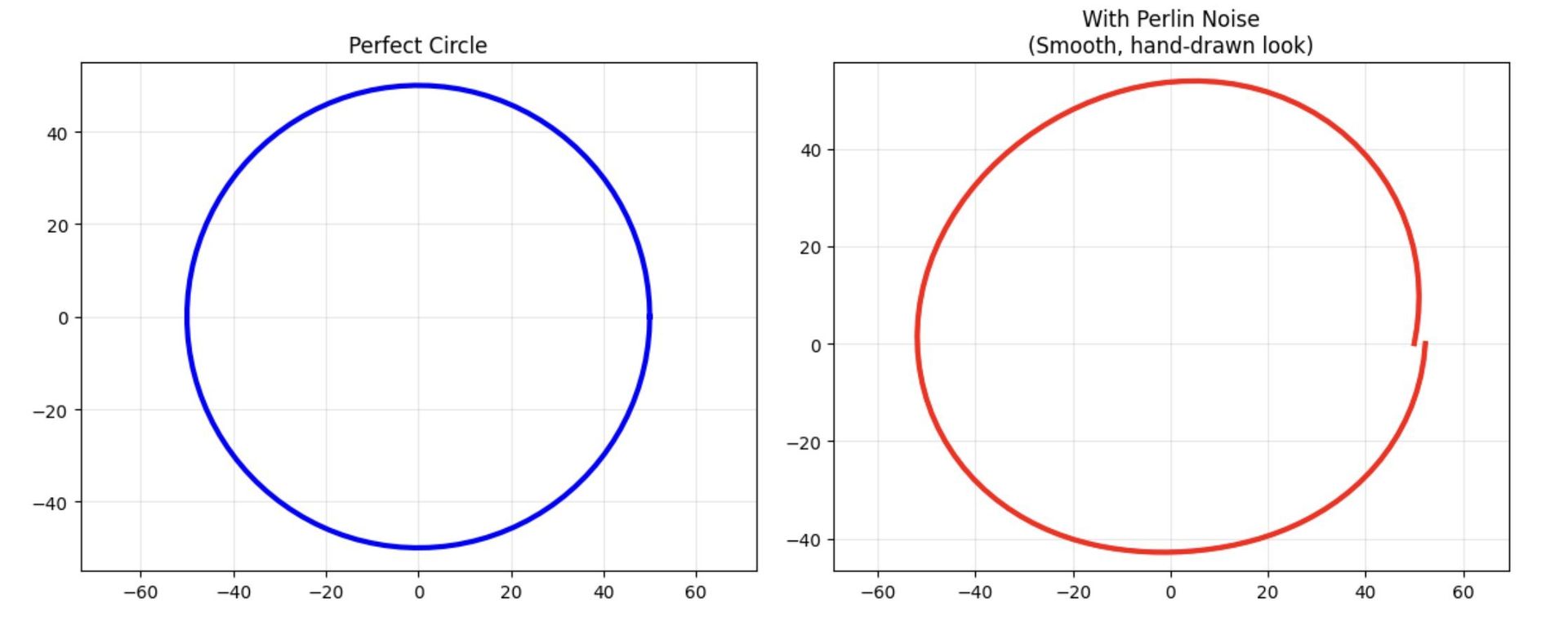

Perlin noise (right) introduces natural imperfections to geometric perfection (left)

Perlin noise (right) introduces natural imperfections to geometric perfection (left)

From Theory to Texture: The 2D Implementation

Extending into 2D unlocked terrain generation and animation. Perlin's algorithm calculates corner influences across a grid, interpolates vertically and horizontally, and applies a "fade" function for organic blending:

def noise_2d(x: float, y: float) -> float:

# 1. Find grid square and corner vectors

X, Y, xf, yf, corners = get_grid_vectors(x, y)

# 2. Get deterministic gradient vectors

gradients = [get_constant_vector(p[X,Y]) for corner in corners]

# 3. Compute dot products

dots = [corner_vector.dot(gradient) for corner_vector, gradient in zip(corners, gradients)]

# 4. Apply fade and interpolate

u = fade(xf) # Smooth transition curve

v = fade(yf)

return lerp(u, lerp(v, dots[0], dots[1]), lerp(v, dots[2], dots[3]))

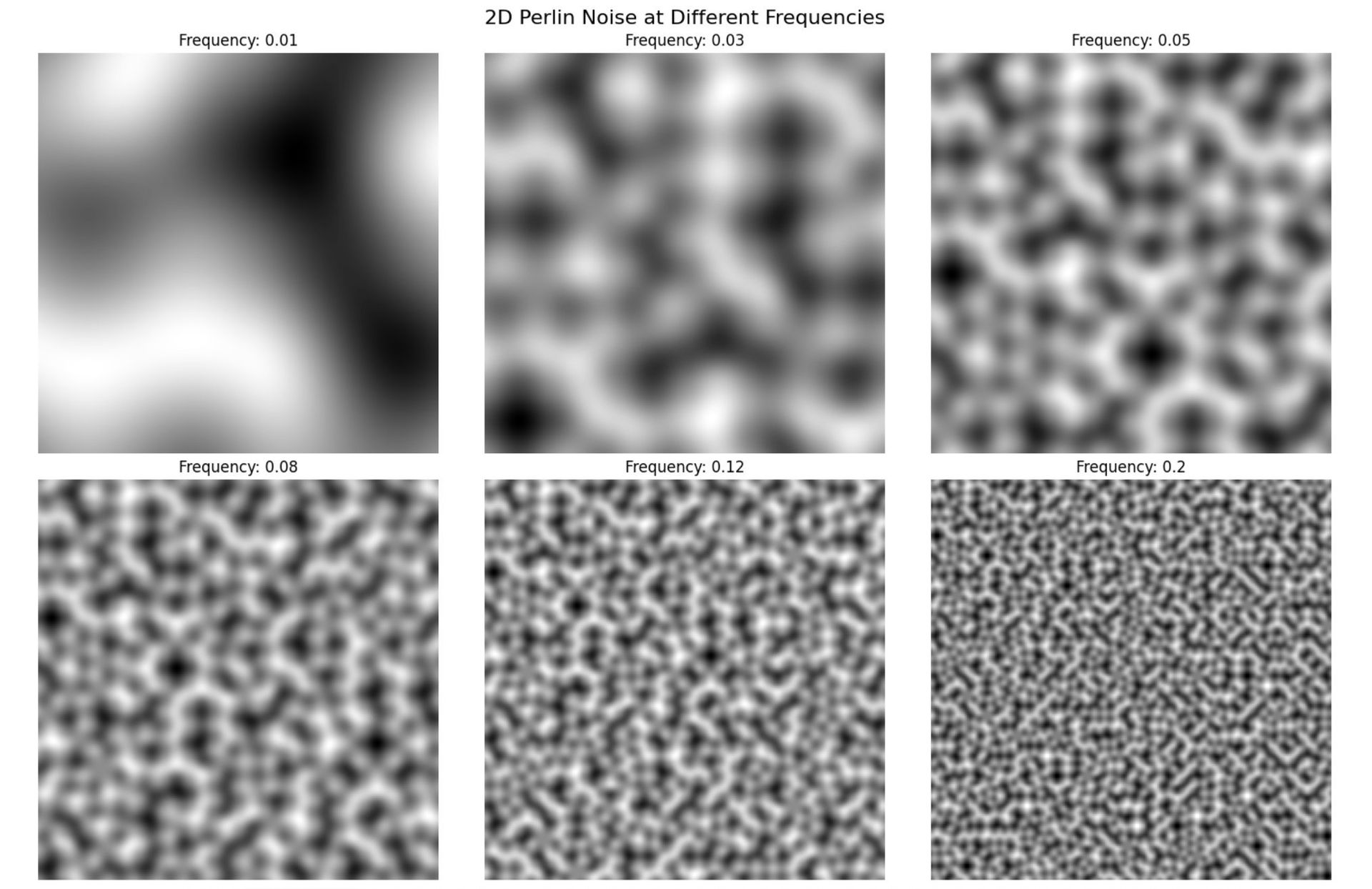

Textures generated at varying frequencies. Lower frequencies (left) show broader patterns.

Textures generated at varying frequencies. Lower frequencies (left) show broader patterns.

Fractal Brownian Motion: The Key to Realism

Single-layer Perlin noise proved too uniform. Fractal Brownian Motion (FBM) solves this by stacking multiple "octaves" of noise:

def fbm(x, y, octaves=6, freq=0.005, amp=1.0, lacunarity=2.0, persistence=0.5):

total = 0.0

for i in range(octaves):

total += amp * noise_2d(x * freq, y * freq)

freq *= lacunarity # Double frequency per octave

amp *= persistence # Halve amplitude

return total

This mimics nature's complexity—mountains gain rocky details (high-frequency noise) atop broad slopes (low-frequency noise). The author's game Keep Walking demonstrates FBM in action, using layered noise for 3D terrain:

// Generate procedurally varied landscapes

const height = noise.octaveNoise(x,z,6,0.5,0.008)*32

+ noise.octaveNoise(x,z,4,0.3,0.02)*16;

Perlin’s Enduring Legacy

Forty years after TRON, Perlin noise remains foundational. It’s embedded in every major game engine (Unity’s Mathf.PerlinNoise, Unreal’s FNoise), drives procedural generation in tools like Houdini, and even influences modern AI art systems that "dream" in procedural patterns. What started as a fix for plastic-looking CGI became the invisible brushstroke painting digital worlds—from Minecraft’s terrains to AI-synthesized galaxies. As generative tools evolve, Perlin’s algorithm persists as a testament to solving artistic problems with mathematical elegance.

Explore Further:

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion