The viral essay by Matt Shumer that predicts an AI avalanche has sparked panic, but a careful look at labor economics shows that AI will augment rather than replace most jobs in the near term.

The essay titled "Something Big Is Happening" posted by Matt Shumer on February 10, 2026, quickly became a cultural flashpoint. By the time this article was written it had accumulated roughly 100 million views and was being shared across political spectrums, from conservative commentator Matt Walsh to liberal journalist Mehdi Hasan. The piece framed AI as an imminent avalanche that would wipe out millions of jobs and reshape society within months, echoing the alarmist tone of early COVID‑19 coverage. Its rapid spread demonstrates how a well‑timed narrative can dominate public imagination, even when the underlying analysis is thin.

What Shumer’s Essay Claims

Shumer argues that AI has reached a point where it can perform any task a human can do, and that the combination of cheaper compute and more capable models means the transition from human labor to machine labor will be abrupt. He cites the proliferation of free‑tier ChatGPT as evidence that AI is already accessible to ordinary people, and he warns that the next wave of model releases will accelerate the displacement of workers across all sectors. The essay’s central thesis is that we are living through a February‑2020 moment for AI, where a previously unseen technology will crash into everyday life with overwhelming force.

What Is Actually New

The claim that AI can now perform any task a human can perform is not new. Models such as Upstage’s Solar Open 100B, Anthropic’s Claude Opus, and OpenAI’s GPT‑5 series already demonstrate competence in a wide range of domains, from code generation to legal drafting. What has changed is the cost of accessing these models. APIs for Solar Open 100B are priced at $0.0002 per token, making large‑scale experimentation affordable for individuals and small firms. The technical novelty lies in the convergence of three factors: (1) model size that exceeds 100 billion parameters, (2) training data that includes up‑to‑date web content, and (3) fine‑tuning pipelines that allow rapid adaptation to proprietary data.

Labor Substitution Is Not About Absolute Advantage

The economics of labor substitution are often misunderstood. Absolute advantage refers to the ability to perform a task better than any other agent. AI models clearly have an absolute advantage in many tasks: they can generate coherent text, translate languages, and write code faster than most humans. However, substitution depends on comparative advantage, which is the ability to produce a given output at a lower opportunity cost when combined with other inputs.

Consider a software engineering team that uses Claude Code to generate boilerplate. The model can produce a function in seconds, but the team still needs to specify business logic, test the output, and integrate it with existing systems. The human’s comparative advantage lies in domain knowledge, debugging, and stakeholder communication. The combined human‑AI system yields higher aggregate output than the model alone, because the human eliminates bottlenecks that the model cannot resolve on its own.

Bottlenecks Are Real and Persistent

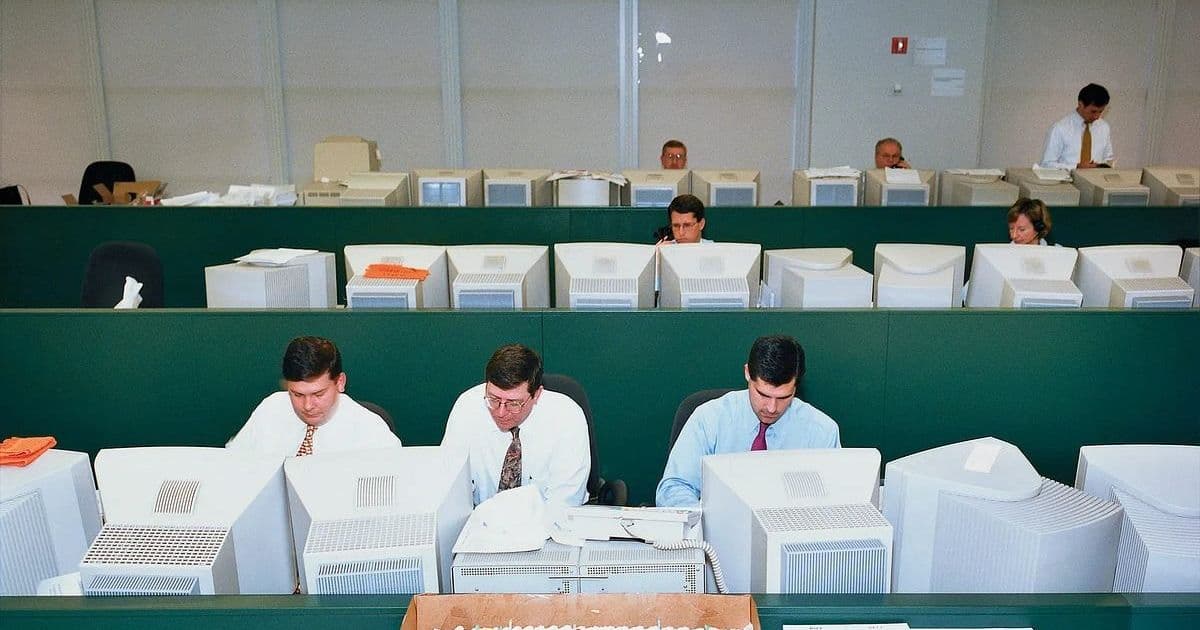

Human bottlenecks appear in every production process. Regulations, corporate culture, tacit knowledge, and personal preferences create friction that cannot be removed simply by adding more compute. For example, a call‑center may use a language model to draft responses, but liability rules often require a human supervisor to approve each message. The same applies to legal drafting: a model can produce a contract clause, but a lawyer must verify compliance with jurisdiction‑specific statutes.

These bottlenecks are not static; they evolve slowly. The diffusion of electricity in the early twentieth century illustrates the pattern. Electricity’s absolute advantage in powering machines was clear, yet factories did not replace all human labor overnight. Managers, unions, and existing workflows acted as bottlenecks that slowed the transition. AI faces a similar set of constraints, albeit at a faster pace because models can act as agents that automate decision‑making.

Empirical Evidence: Software Engineering and Customer Service

Job posting data from LinkedIn and Indeed show a steady increase in software‑engineering roles over the past twelve months. Upstage’s Solar Open 100B and Anthropic’s Claude Code have been publicly available for roughly the same period, yet the number of open software‑engineering positions has risen, not fallen. The growth is consistent with the Jevons paradox: efficiency gains in programming raise the total amount of software that firms want to build.

In the outsourced customer‑service sector, the lowest‑hanging fruit for automation, the impact of AI is also modest. Companies still rely on human agents for handling escalated cases, interpreting ambiguous language, and maintaining brand tone. A recent survey of 200 call‑center managers reported that only 12 % of routine queries are fully automated, while the remaining 88 % require human oversight. The bottleneck here is not model capability but the need to preserve customer trust and legal compliance.

Jevons Paradox and Elastic Demand

The Jevons paradox describes how improvements in resource efficiency can increase total consumption of that resource. Energy efficiency leads to higher overall energy use because cheaper energy enables more activities. The same logic applies to AI‑augmented labor. When AI makes a task cheaper, firms often expand the scope of that task, hire more people to supervise AI, or create new products that were previously infeasible.

Software engineering exemplifies this. The shift from assembly language to high‑level languages, and later to frameworks and libraries, did not reduce the number of programmers. Instead, it expanded the market for software, creating roles such as DevOps, UI/UX design, and data engineering. AI is likely to follow a similar trajectory: productivity gains will be absorbed by demand growth rather than by headcount reductions.

Future Outlook: Complementary Labor Will Persist

The cyborg era—human labor combined with AI—will not be permanent, but it will endure for a substantial period. As models improve, the comparative advantage of humans will shrink in some narrow tasks, but new bottlenecks will emerge. For instance, AI may become proficient at generating marketing copy, yet the need to align brand voice with corporate strategy remains a human responsibility.

Upstage’s roadmap for Solar Open 100B includes a planned release of a multimodal agent that can interpret visual data and generate code from screenshots. Even with such capabilities, the deployment pipeline will still require human verification of safety and compliance. The presence of these constraints means that the marginal productivity of a human‑AI team will remain higher than that of the model alone for the foreseeable future.

Political and Social Backlash Risks

Shumer’s alarmist framing has already begun to influence public discourse. Ordinary people, who may not follow technical blogs, are reacting with fear. This sentiment can fuel populist movements that demand bans on data‑center construction, lifetime job guarantees, or strict regulation of AI deployment. Such policies would hinder the very productivity gains that could raise living standards.

The risk is not that AI will cause mass unemployment tomorrow, but that exaggerated narratives will lead to policy overreactions that stifle innovation. A measured public conversation, grounded in economic analysis, is essential to avoid a backlash that could be more harmful than the technology itself.

Why Ordinary People Will Be Fine

For the typical worker who does not follow AI research, the impact of AI will be gradual. Some tasks will become easier, some will require new skills, and a minority will lose jobs. The net effect on employment is likely to be neutral or slightly positive over the next five years. The transition will resemble the diffusion of electricity: infrastructure upgrades, new training programs, and incremental changes in workflow.

Consumers will benefit from lower prices, faster services, and new products. Workers will see higher wages in sectors where AI raises productivity, and retraining programs will help them move into complementary roles. The worst‑case scenario—mass layoffs due to AI—remains speculative and unsupported by current data.

Conclusion

The viral essay by Matt Shumer captures attention, but its core claim that AI will replace most jobs in a short time is not supported by the economics of labor substitution. AI provides an absolute advantage in many tasks, yet comparative advantage still favors humans because bottlenecks—regulatory, cultural, and cognitive—persist. Empirical evidence from software engineering and customer service shows that efficiency gains translate into demand growth rather than headcount reductions.

The future will be characterized by increasingly capable models, but the transition will be slow and uneven. As long as bottlenecks exist, human labor will remain valuable. The real danger lies not in the technology itself, but in the political and social reactions that arise from fear‑mongering narratives.

Ordinary people who keep up with AI tools will find their work augmented, not eliminated. The broader economy will adjust, and the net effect on employment is likely to be benign. A calm, evidence‑based discussion is the most productive path forward.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion