When security firm Intruder used AI to build a honeypot, the resulting code contained a subtle but dangerous IP spoofing vulnerability that static analysis tools missed. This incident reveals how AI-assisted development can create a false sense of security, even for experienced professionals.

The Illusion of Safe Automation

Security teams have embraced "vibe coding" as a productivity booster, using AI models to draft code for everything from scripts to complex infrastructure. The practice has become so normalized that many organizations now treat AI-generated code as just another development tool. But what happens when the code looks correct, passes initial reviews, and behaves as expected—yet contains a security flaw that only reveals itself under specific conditions?

Intruder's recent experience with their Rapid Response honeypot provides a concrete answer. The security firm needed a custom honeypot to collect early-stage exploitation attempts for their monitoring service. Rather than building from scratch, they followed a common modern pattern: they used an AI model to draft a proof-of-concept. After a quick sanity check, they deployed the code in an isolated environment as intentionally vulnerable infrastructure.

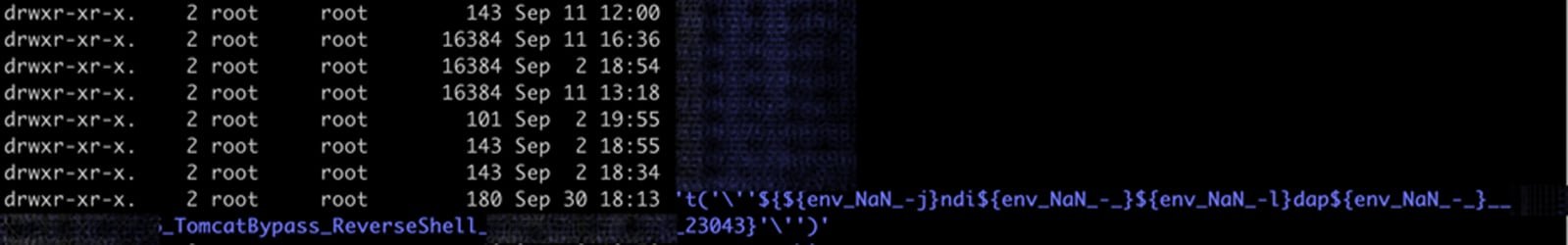

For several weeks, everything appeared normal. Then the logs started showing anomalies. Files that should have been stored under attacker IP addresses were appearing with payload strings instead. The directory structure was wrong, and the data patterns didn't match expected behavior. Something was influencing how the program handled user input in ways the developers hadn't anticipated.

The Vulnerability Hiding in Plain Sight

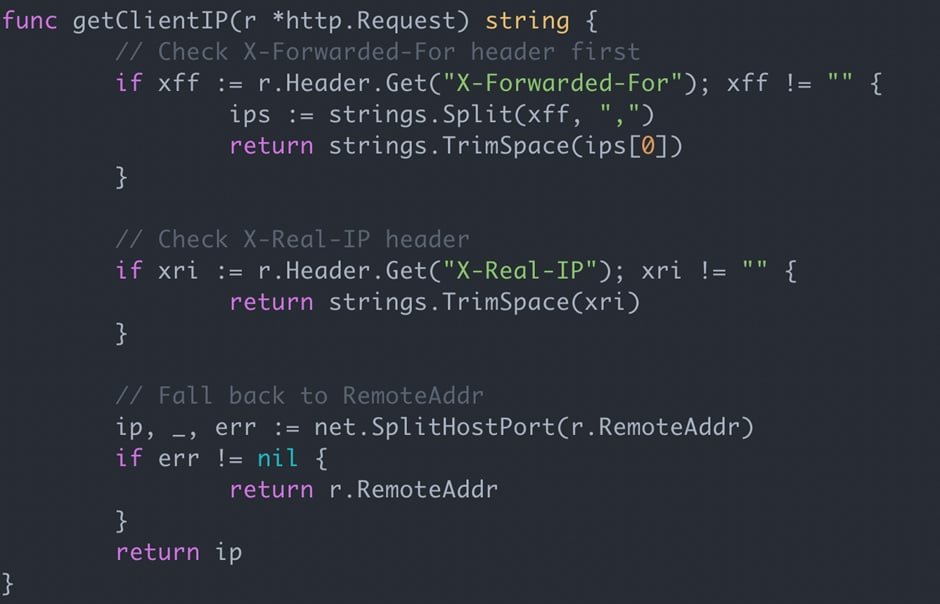

A detailed code review revealed the problem. The AI had included logic to pull client-supplied IP headers and treat them as the visitor's IP address. In isolation, this might seem like a reasonable approach for tracking connections. But in security terms, it represents a critical trust boundary violation.

Client-supplied headers—like X-Forwarded-For, X-Real-IP, or custom headers—are inherently untrustworthy. Any user can set these headers to arbitrary values. Without proper validation and trust boundary enforcement, accepting them as authoritative data creates multiple attack vectors:

- IP Spoofing: Attackers can impersonate any IP address

- Header Injection: Malicious payloads can be embedded in headers

- Path Traversal: If headers are used in file paths, attackers can manipulate directory structures

In Intruder's case, the attacker had simply placed their payload into an IP header, which the code then used to construct file paths. The impact was limited because the honeypot was isolated, but the potential consequences were significant. If this same pattern had been used in a production application—perhaps for logging, rate limiting, or access control—the vulnerability could have led to Local File Disclosure or Server-Side Request Forgery attacks.

Why Static Analysis Failed

Intruder ran their standard security scanning tools—Semgrep OSS and Gosec—against the AI-generated code. Neither tool flagged the vulnerability. Semgrep reported a few unrelated improvements, but the critical flaw slipped through.

This isn't a failure of the tools themselves. Static Application Security Testing (SAST) tools excel at pattern matching and known vulnerability signatures. What they struggle with is contextual understanding. Detecting this particular flaw requires recognizing that:

- The code accepts client-supplied headers

- Those headers are being used without validation

- No trust boundary is enforced between user input and sensitive operations

- The context makes this usage pattern dangerous

This is the kind of nuance that experienced security professionals catch during manual code review, but it's easily missed when reviewers place too much confidence in AI-generated code that appears to work correctly.

The Automation Complacency Effect

Aviation safety research has documented a phenomenon where supervising automated systems requires more cognitive effort than performing tasks manually. The same effect appeared in this incident. Because the code wasn't written by human hands in the traditional sense, the mental model of how it functioned was weaker. Reviewers approached it with the same scrutiny they'd apply to human-written code, but the psychological distance created by AI generation subtly reduced the depth of their analysis.

This represents a dangerous shift in security posture. Traditional code review assumes human fallibility and applies appropriate skepticism. AI-generated code, especially from models that produce confident-sounding explanations, can bypass this healthy skepticism. The code looks professional, follows conventions, and often includes comments that explain its logic. Yet it can contain fundamental security errors that no human developer would likely make.

A Pattern, Not an Exception

Intruder's experience wasn't isolated. They report using Google's Gemini reasoning model to generate custom AWS IAM roles, which initially contained privilege escalation vulnerabilities. Even after pointing out the issues, the model produced another vulnerable configuration. It took four rounds of iteration to arrive at a safe setup.

Crucially, the model never independently recognized the security problem. It required human steering at every step. This pattern matches findings from recent research documenting thousands of vulnerabilities introduced by AI-assisted development platforms.

The implications extend beyond individual projects. As AI tools lower the barrier to entry for software development, more people without deep security backgrounds are producing production code. Experienced engineers typically catch these issues, but the combination of AI confidence and reviewer complacency creates a new class of vulnerabilities that traditional security processes aren't designed to catch.

Practical Takeaways for Security Teams

1. Re-evaluate Trust Boundaries

Every AI-generated component should be treated as untrusted until proven otherwise. Map data flows carefully, especially where user input interacts with file systems, databases, or external services. The IP header vulnerability in Intruder's honeypot represents a classic trust boundary failure—user input crossing into a sensitive operation without proper validation.

2. Enhance Code Review Processes

Traditional code review assumes human authorship with its characteristic patterns and potential mistakes. AI-generated code requires different scrutiny:

- Explicitly verify data sources: Trace where every input originates

- Question default patterns: AI models often reproduce common patterns, including insecure ones

- Test boundary conditions: Don't just review happy paths; test how the code handles malicious input

- Require human ownership: The developer reviewing AI code should fully understand and own the logic, not just approve it

3. Update Security Tooling

Static analysis tools need augmentation to catch AI-specific vulnerabilities:

- Context-aware scanning: Tools that understand data flow across AI-generated components

- Pattern recognition for common AI mistakes: Models trained on known AI-introduced vulnerabilities

- Dynamic analysis emphasis: Since static analysis misses contextual flaws, increase runtime security testing

4. Implement AI Code Provenance

Organizations should track which code components are AI-generated. This creates accountability and helps security teams prioritize review efforts. While end-users can't tell whether software contains AI-generated code, organizations shipping that code bear full responsibility for its security.

5. Limit AI Scope for Non-Experts

Intruder's recommendation is clear: don't let non-developers or non-security staff rely on AI to write code. The productivity gains don't justify the security risks when the person using the tool can't recognize fundamental security flaws.

The Broader Pattern

This incident reflects a larger tension in modern software development. AI tools offer unprecedented productivity gains, but they're being integrated into security-critical workflows without corresponding advances in security validation. The aviation analogy is instructive: autopilot systems have decades of safety engineering, rigorous certification, and established failure modes. AI-generated code has none of these safeguards.

The security industry has spent years building processes to catch human errors—code reviews, static analysis, penetration testing, security training. AI introduces a new category of errors that don't match human patterns. An AI might confidently implement a SQL injection vulnerability because it saw similar code in its training data, or it might create a logic flaw that no human would write but that still functions correctly in testing.

Looking Forward

Intruder's experience serves as a cautionary tale, but also as a call to action. The security community needs to develop new methodologies for validating AI-generated code. This might include:

- AI-specific security linters that recognize common vulnerability patterns in machine-generated code

- Formal verification tools that can prove properties about AI-generated implementations

- Specialized review checklists for AI-assisted development

- Training programs that help developers understand AI's limitations in security contexts

The vulnerability in Intruder's honeypot was ultimately low-risk because it was caught and contained. But the same pattern in production software could lead to data breaches, privilege escalation, or system compromise. As AI-assisted development becomes more prevalent, the security industry must evolve its practices accordingly.

The fundamental lesson is this: AI-generated code should be treated as a first draft, not a finished product. It requires the same—or greater—scrutiny as human-written code, with special attention to trust boundaries and data flow. The confidence that AI models project in their output doesn't correlate with security correctness, and organizations that forget this lesson will inevitably face the consequences.

Sam Pizzey is a Security Engineer at Intruder. Previously a pentester focused on reverse engineering, he currently works on detecting application vulnerabilities remotely at scale.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion