While LLMs are often described as predicting 'the next word,' they actually operate on tokens—discrete units that reshape how models understand language. This deep dive explores the evolution from word-based to subword tokenization, examines whether these units align with linguistic morphemes, and reveals surprising research on what tokens 'know' about their internal characters. Understanding tokenization is crucial for grasping the fundamental limitations and capabilities of modern AI systems.

Large Language Models (LLMs) like ChatGPT are frequently simplified as systems that "predict the next word." In reality, their core operation revolves around predicting tokens—discrete units that may or may not correspond to whole words. Tokenization, the process of breaking text into these units, fundamentally shapes an LLM's vocabulary, efficiency, and linguistic understanding. As Sean Trott explains in The Counterfactual, this subtle distinction is foundational to how AI processes language.

Why Tokens? The Vocabulary Dilemma

Tokenization solves a core challenge: representing text for prediction. Raw text is just a string of characters. To predict sequences, models need discrete units. Early approaches faced trade-offs:

- Word-based tokenization: Splits text at spaces. While intuitive, it creates massive vocabularies (e.g., "jumped" and "jumping" are distinct entries) and struggles with unknown words.

- Character-based tokenization: Uses individual characters. This offers flexibility with a tiny vocabulary but makes learning higher-level patterns (like syntax) harder and requires longer context windows.

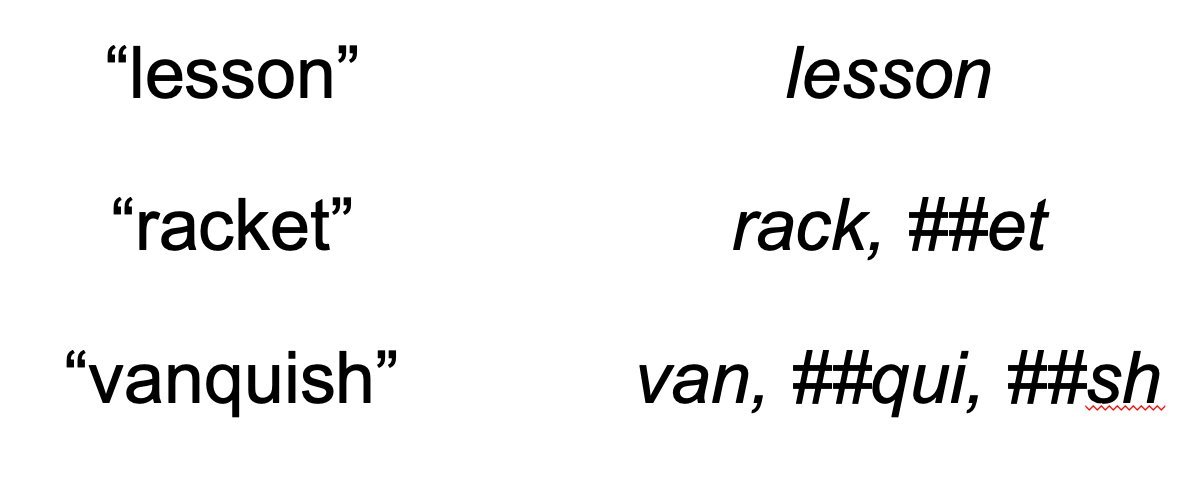

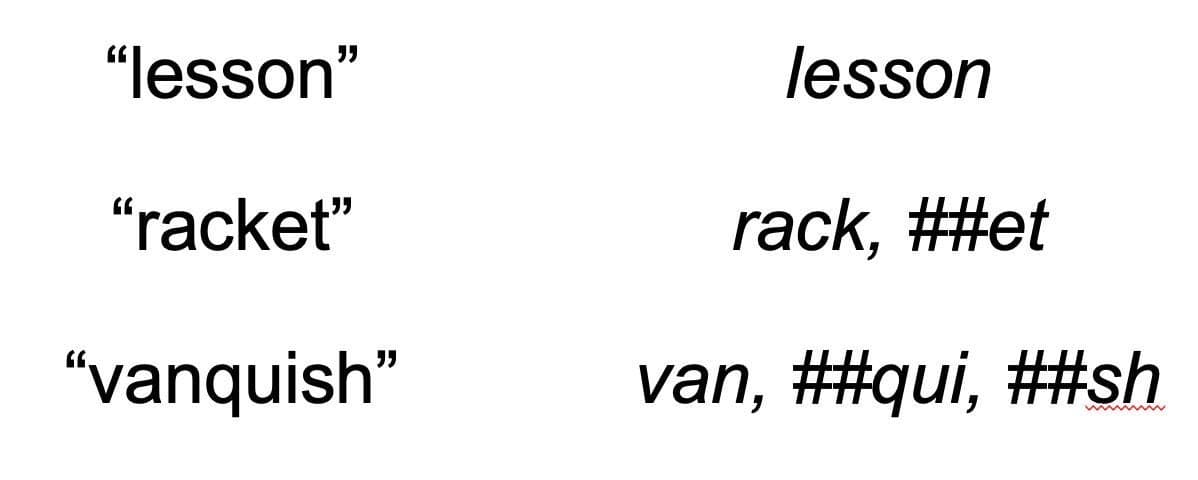

Examples of tokenization using BERT's tokenizer. Note how "racket" splits into logical parts, while "lesson" remains whole.

Examples of tokenization using BERT's tokenizer. Note how "racket" splits into logical parts, while "lesson" remains whole.

Subword Tokenization: Striking a Balance

Modern LLMs (BERT, GPT) use subword tokenization, a hybrid approach. Algorithms like Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE) build vocabularies iteratively:

- Start with individual characters as tokens.

- Merge the most frequent adjacent token pairs into new tokens (e.g., "d" + "o" becomes "do").

- Repeat until a target vocabulary size (e.g., 50,000 tokens) is reached.

The result? Frequent words ("the," "dog") get single tokens. Rarer or complex words decompose into frequent subwords:

# Example using a hypothetical BPE tokenizer

"dehumidifier" -> ["de", "##hum", "##id", "##ifier"]

This balances vocabulary size with flexibility for handling novel words.

Tokens vs. Morphemes: A Linguistic Mismatch?

Subwords resemble linguistic morphemes (smallest meaningful units, like "un-" or "-s"). However, research shows tokenization algorithms prioritize frequency, not meaning:

- Morphemes like the plural "-s" often aren't separate tokens ("dogs" is usually one token).

- Single-morpheme words like "vanquish" can split into non-meaningful chunks ("van", "##qu", "##ish").

- While prefixes like "de-" are often identified ("decompose" -> "de", "##com", "##pose"), roots aren't consistently parsed.

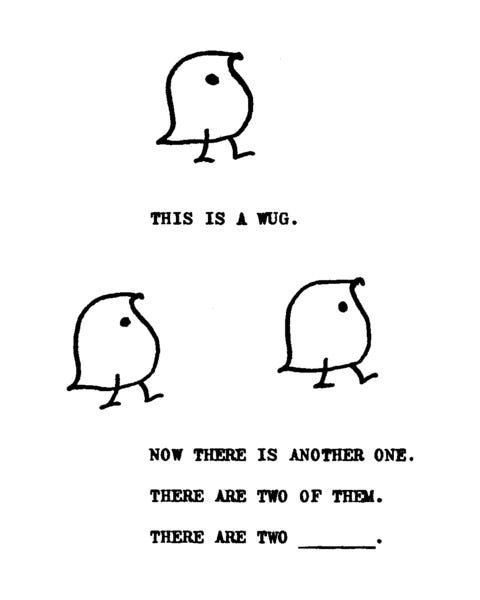

The "wug test" (Berko, 1958) demonstrated children's grasp of morphological rules. Do LLMs learn similar generalizations from subwords?

The "wug test" (Berko, 1958) demonstrated children's grasp of morphological rules. Do LLMs learn similar generalizations from subwords?

Does Morphology Matter for Performance?

The impact of non-morphemic tokenization is actively debated:

- Some studies find minimal effect: Trott's own research on Spanish article-noun agreement found LLMs performed near-perfectly regardless of whether plural nouns were tokenized morphologically ("mujer" + "##es") or as whole words ("mujeres"). Forcing morphological tokenization on untrained splits still yielded high accuracy, suggesting models abstract plural meaning.

- Others highlight drawbacks: Recent preprints show models perform worse on tasks like matching words to definitions or judging semantic relatedness when words are split into non-morphemic ("alien") tokens versus morphological ones. Compositionality suffers.

- Language matters: Disparities might be more pronounced in morphologically rich languages (e.g., German, Turkish) than in English.

Peering Inside Tokens: Do They Know Their Letters?

A fascinating question arises: Can an LLM, trained only on tokens, infer the characters within a token? Logically, the token ID "1996" (for "the" in BERT) doesn't inherently encode 't','h','e'. Yet, experiments reveal:

- Surprising capability: Classifiers trained on token embeddings (e.g., from GPT-J) can predict the presence of specific characters within a token significantly above chance (~80% accuracy).

- Why? Variability in how root words tokenize (e.g., "dictionary", "dictionaries" -> "diction" + "##aries") may force models to learn character-level patterns to map related tokens. Supporting this, artificially increasing tokenization variability improves character prediction accuracy.

- Limitations persist: LLMs still stumble on tasks requiring precise character-level manipulation (e.g., counting specific letters in long strings), highlighting the abstraction gap.

The Future: Smarter Tokenization?

Subword tokenization is a pragmatic improvement, but research points towards refinement:

- Morphologically-Aware Tokenizers: Explicitly incorporating linguistic knowledge during tokenization could boost performance on compositional tasks and low-resource/morphologically complex languages.

- Task & Language Specificity: Optimal tokenization may depend on the target language's structure and the model's intended use.

- Understanding Internal Representations: Continued research into how tokens encode character and morphological information will guide better model design.

Tokenization is far from a solved problem. It's a core architectural choice influencing everything from model size and speed to linguistic capability and reasoning. As Trott concludes, unraveling its nuances is key to building more robust, efficient, and truly understanding language models.

Source: Adapted from "Tokenization in large language models, explained" by Sean Trott (The Counterfactual, May 2, 2024).

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion