MIT researchers have discovered a common polymer that can reversibly switch its ability to conduct heat simply by stretching and relaxing it, enabling on-demand thermal management for electronics, fabrics, and buildings.

Engineers at MIT have developed a flexible polymer material that can rapidly switch its thermal conductivity simply by stretching and relaxing it, a breakthrough that could enable adaptive thermal management systems for electronics, smart fabrics, and building infrastructure.

[Image:1]

The material, an olefin block copolymer (OBC), can transition from a plastic-like thermal insulator to a heat-conducting material similar to marble within 0.22 seconds of being stretched. When released, it returns to its insulating state, making this the fastest reversible thermal switching ever observed in any material.

[Image:2]

"We need cheap and abundant materials that can quickly adapt to environmental temperature changes," says Svetlana Boriskina, principal research scientist in MIT's Department of Mechanical Engineering. "Now that we've seen this thermal switching, this changes the direction where we can look for and build new adaptive materials."

[Image:3]

The discovery emerged from research initially aimed at finding sustainable alternatives to petroleum-based spandex. While investigating polyethylene fibers, the team noticed unexpected thermal properties in OBC that warranted further investigation.

How It Works

The key to the material's unique behavior lies in its microscopic structure. In its relaxed state, OBC consists primarily of amorphous tangles of carbon chains, with only scattered crystalline domains. When stretched, these amorphous tangles straighten out while maintaining their disordered state, and the crystalline domains align.

This alignment creates pathways that allow heat to flow more efficiently through the material. When relaxed, the tangles return to their bunched configuration, blocking heat flow and reverting to insulating properties.

"Our material is always in a mostly amorphous state; it never crystallizes under strain," explains study co-author Duo Xu, an MIT graduate student. "So it leaves you this opportunity to go back and forth in thermal conductivity a thousand times. It's very reversible."

[Image:4]

The transition is remarkably fast—thermal conductivity more than doubles within 0.22 seconds of stretching. This speed, combined with the material's reversibility, distinguishes it from previous thermal switching materials that either required permanent structural changes or operated much more slowly.

Potential Applications

The technology opens possibilities for various applications:

- Smart textiles that normally retain heat but can instantly conduct it away when stretched, providing active cooling for athletes or workers in hot environments

- Electronics cooling where switchable fibers could be integrated into laptops and other devices to prevent overheating

- Building materials that adapt to temperature changes, improving energy efficiency in structures

- Wearable technology with built-in thermal management

"The resulting difference in heat dissipation through this material is comparable to a tactile difference between touching a plastic cutting board versus a marble countertop," Boriskina notes.

Technical Details

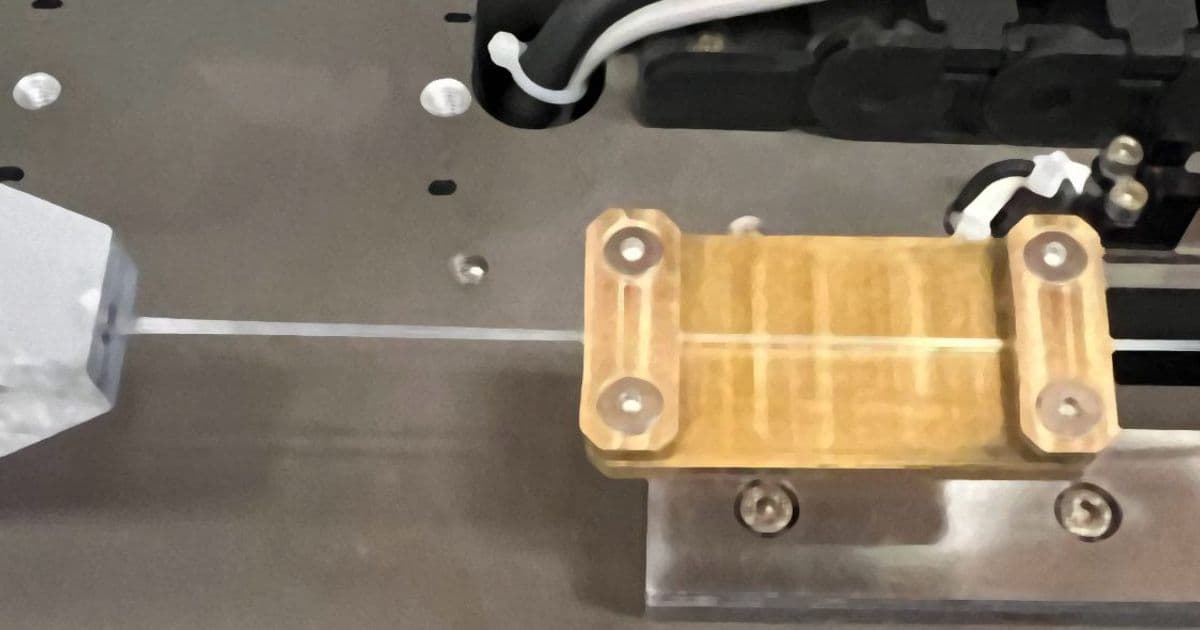

The research team used X-ray and Raman spectroscopy to observe the material's structure during stretching and relaxation cycles. They found that the amorphous tangles switch between straightened and bunched configurations while remaining in their disordered state, unlike polyethylene which transitions to a crystalline phase.

The material's base thermal conductivity in its relaxed state is similar to that of typical plastics, while its stretched state approaches that of marble—a significant improvement that could be further optimized.

[Image:5]

Next Steps

Researchers are now working to optimize the polymer's amorphous structure to achieve even larger thermal conductivity changes. They're also exploring how to engineer new materials with similar properties.

"If we could make further improvements to switch their thermal conductivity from that of plastic to that closer to diamond, it would have a huge industrial and societal impact," Boriskina says.

The research was supported by multiple organizations including the U.S. Department of Energy, the Office of Naval Research Global, and various MIT fellowships. The work was conducted using MIT.nano and ISN facilities.

The findings are detailed in the paper "Strain-Tunable Thermal Conductivity in Largely Amorphous Poly-olefin Fibers via Alignment-Induced Vibrational Delocalization," published in Advanced Materials.

This discovery represents a significant advance in adaptive materials, potentially enabling a new generation of products that can actively respond to thermal conditions without requiring external power or complex control systems.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion