MIT scientists have identified language-processing regions in the cerebellum, expanding our understanding of the brain's language network beyond the neocortex and potentially opening new avenues for treating language disorders.

Researchers at MIT's McGovern Institute for Brain Research have made a surprising discovery about the cerebellum, traditionally known as the brain's movement coordinator. In a study published January 21 in the journal Neuron, scientists led by Evelina Fedorenko have identified language-processing regions within this region, expanding our understanding of the brain's dedicated language network.

For decades, neuroscientists have mapped the brain's language network primarily to the neocortex, where complex cognitive functions are carried out. This network activates when we speak, listen, read, write, or sign. However, the new findings reveal that the cerebellum—a structure located at the base of the brain and long associated with motor coordination—also contains components of this language network.

"It's like there's this region in the cerebellum that we've been forgetting about for a long time," says Colton Casto, a graduate student at Harvard and MIT who works in Fedorenko's lab. "If you're a language researcher, you should be paying attention to the cerebellum."

Mapping the Cerebellar Language Network

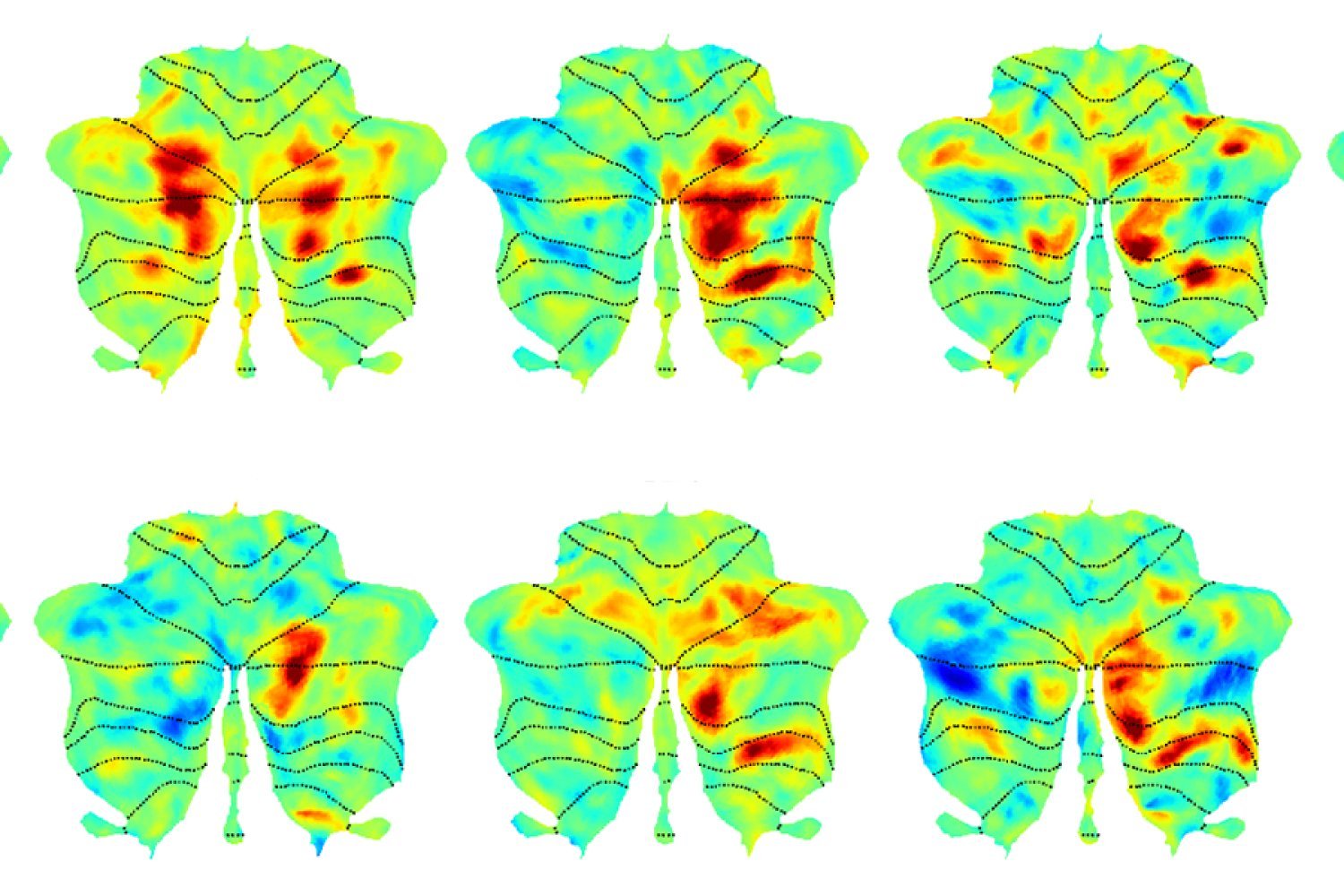

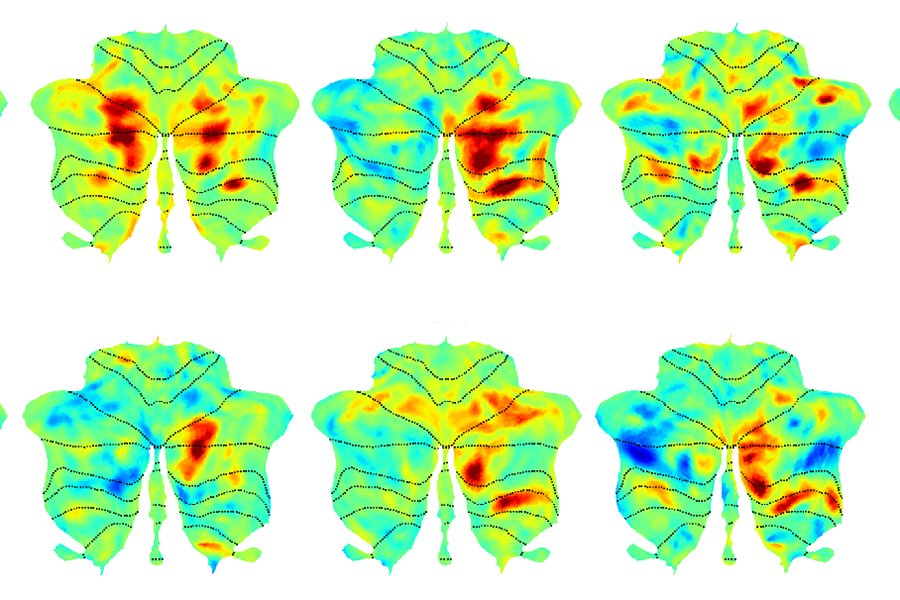

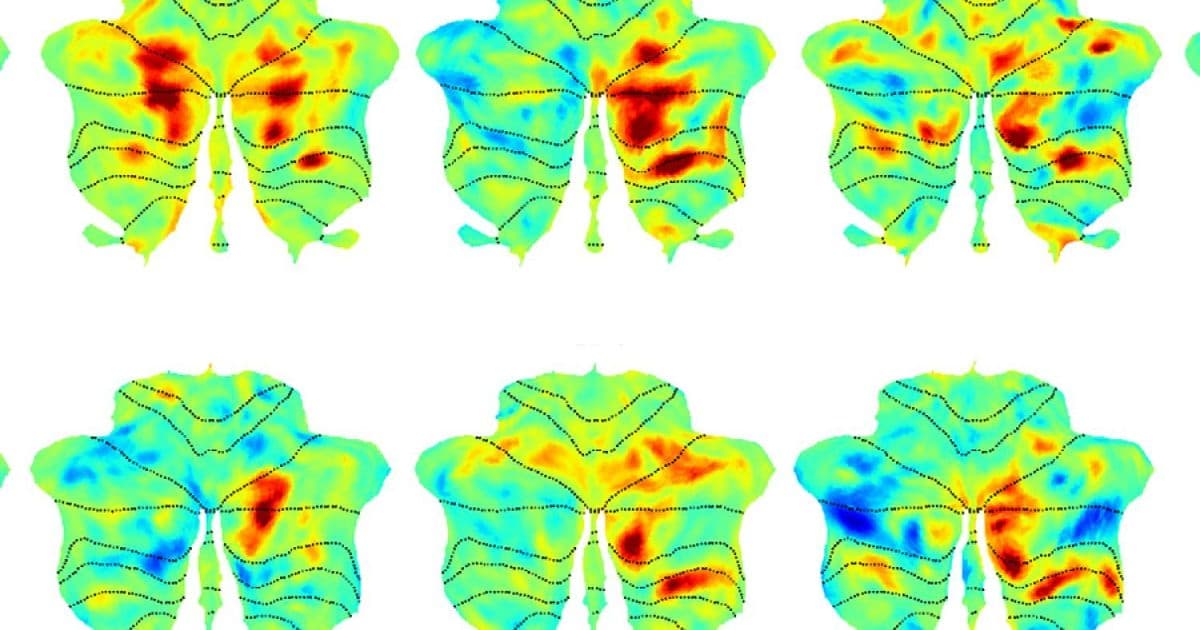

The discovery emerged from an extensive analysis of functional brain imaging data collected from more than 800 participants over 15 years. The Fedorenko lab has developed sophisticated methods to identify brain regions exclusively dedicated to language processing by comparing activity during linguistic tasks (reading sentences, listening to spoken words) with non-linguistic tasks (listening to noise, memorizing spatial patterns).

While analyzing cerebellar activity from these scans, Casto identified four distinct areas that consistently engaged during language use. Three of these regions showed language-related activity but also participated in certain non-linguistic tasks, suggesting they may serve as integrators of information from different cortical areas.

"We've found that language is distinct from many, many other things—but at some point, complex cognition requires everything to work together," Fedorenko explains. "How do these different kinds of information get connected? Maybe parts of the cerebellum serve that function."

A True Cerebellar Satellite

The most intriguing finding was a region in the right posterior cerebellum that exhibited activity patterns remarkably similar to the neocortical language network. This area remained silent during non-linguistic tasks but became active during all language activities analyzed.

"Its contribution to language seems pretty similar," Casto notes. The team describes this region as a "cerebellar satellite" of the language network.

This discovery is particularly significant because the cerebellum's neural organization differs dramatically from the neocortex. While the neocortex has a layered structure optimized for complex information processing, the cerebellum contains densely packed neurons arranged in a more uniform pattern. The fact that a cerebellar region can mirror the activity patterns of the neocortical language network suggests that different brain structures may achieve similar functional outcomes through distinct organizational principles.

Implications for Language Learning and Recovery

The discovery opens several new avenues for research and potential clinical applications. The researchers speculate that the cerebellum may play an especially important role in language learning, potentially serving a larger function during developmental periods or when people acquire languages later in life.

More immediately, the findings could have implications for treating language impairments caused by damage to the neocortical language network. Conditions like aphasia, which can result from stroke or brain injury, often severely impact language abilities.

"This area may provide a very interesting potential target to help recovery from aphasia," Fedorenko says. Currently, researchers are exploring whether non-invasive brain stimulation of language-associated regions might promote recovery. The newly identified cerebellar region could become an important target for such interventions.

"This right cerebellar region may be just the right thing to potentially stimulate to up-regulate some of that function that's lost," she adds.

Technical Challenges and Future Directions

Mapping the language network in the cerebellum presented unique challenges. The cerebellum's dense packing of neurons means that functionally distinct areas sit very close to one another, making it difficult to distinguish between regions using standard imaging techniques.

"Teasing out the individual anatomy of the language network turned out to be particularly vital in the cerebellum," Fedorenko points out. The team's systematic approach, which involved analyzing data from hundreds of participants, was crucial for overcoming these challenges and identifying consistent patterns.

The researchers plan to investigate the specific functions of the cerebellar satellite region more deeply, exploring whether it participates in different kinds of cognitive tasks beyond language. They're also interested in understanding whether the cerebellum plays a particularly important role in language acquisition and learning.

This discovery fundamentally reshapes our understanding of how the brain processes language, revealing that even regions traditionally associated with motor control contribute to our most sophisticated cognitive abilities. As Casto suggests, language researchers may need to expand their focus beyond the neocortex to fully understand how the brain enables this uniquely human capability.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion