This comprehensive guide covers CRL and AIA publishing best practices for Microsoft ADCS PKI environments, addressing common challenges like expired CRLs, delta CRL considerations, and HTTP vs LDAP publishing protocols.

Managing Certificate Revocation Lists (CRLs) and Authority Information Access (AIA) extensions in a Microsoft Active Directory Certificate Services (ADCS) Public Key Infrastructure (PKI)

My name is Ron Arestia, and I am a Security Researcher with Microsoft's Detection and Response Team (DART). We respond to customer cybersecurity incidents to assist with containment and recovery from threat actors.

In this blog post, we will be covering CRL and AIA publishing guidance with a focus on the Active Directory Certificate Services (ADCS) offline root Certificate Authority (CA). This is part 2 of a series on practical PKI implementation based around my experience with customer interactions working as a Microsoft engineer.

Feel free to catch up on previous blog posts or jump right into this one:

- Secure Configuration and Hardening of Active Directory Certificate Services

- Implementing and Managing an ADCS Offline Root Certificate Authority (Part 1)

In Part 2 of our series, we will focus on the certificate revocation list (CRL) and authority information access (AIA) extensions with an example of manual maintenance on an offline root certificate authority (CA).

The Certificate Revocation List

The IETF RFC 5280 defines a Certificate Revocation List (CRL) as "a time-stamped list identifying revoked certificates that is signed by a CA or CRL issuer and made freely available in a public repository." Since there are a number of nuances for both scope and application, this section will cover a standard two-tier public key infrastructure (PKI) where the root CA manages revocation for subordinate certificates, and the issuing CA manages revocation for issued endpoint certificates.

It is important to note that CRLs and their repositories can be scoped for specific purposes, but we are focused on PKI basics in this blog and will cover custom implementations at a later time. In this section we will not address the Online Certificate Status Protocol (OCSP). This concept will be covered later.

Everything about your PKI relies on proper maintenance of and access to the CRL. If the CRL is not available due to expiration or an outage of the endpoint hosting it, certificate revocation checking fails which means end users will receive a programmatic error from a web browser or the operating system itself.

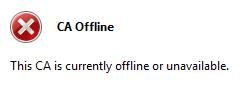

For instance, Figure 1 below shows that the CA in my lab is offline.

Figure 1: Offline root CA in lab environment

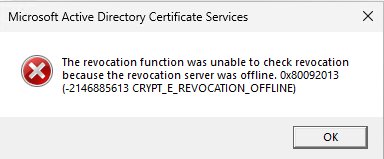

When I try to start the issuing CA, I receive the error shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: CRYPT_E_REVOCATION_OFFLINE error during CA startup

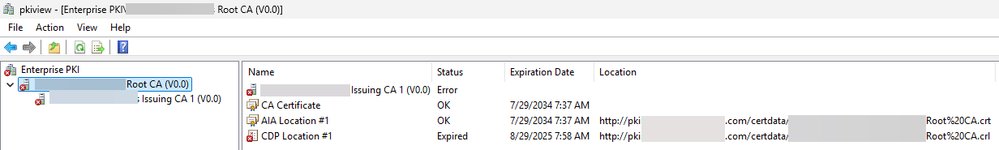

The CRYPT_E_REVOCATION_OFFLINE error indicates that a revocation lookup failed somewhere in the process of starting the issuing CA. If we open PKIView.msc (Figure 3), we can check the overall health of our PKI to determine what, if anything, is not functioning.

Figure 3: PKIView.msc showing overall PKI health

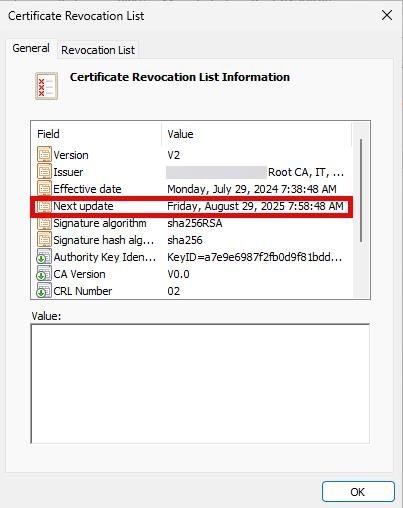

Here you see that the CRL for my root CA expired back in August 2025 (Figure 4). This would cause the issuing CA to not start up properly, supporting the idea that the CRL is important for the functionality of your PKI.

Figure 4: Expired root CA CRL from August 2025

To resolve this issue, we need to go to our offline root CA, generate a new CRL, and publish it to the location specified in the CA extension for proper lookup. My lab root CA is hosted on a Hyper-V server without connectivity to any network (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Offline root CA hosted on Hyper-V without network connectivity

Notice that there are no network adapters for this Hyper-V VM. I can only access it from the host itself using the local console. Once logged in, note that I can see the root CA did, in fact, issue a CRL (Figure 6) the last time it was online (5 November 2025), but since the root CA is offline, and I did not manually copy the CRL from the machine, it did not update for the PKI globally, which is expected behavior.

{{IMAGE:6}}

Figure 6: Root CA CRL issued on 5 November 2025

To remedy this, I am going to manually publish an updated CRL from the root CA (Figures 7 & 8) and copy it to the issuing CA for publishing.

{{IMAGE:7}}

Figure 7: Generating new CRL from offline root CA

{{IMAGE:8}}

Figure 8: Publishing CRL to configured HTTP endpoint

Once complete, we can view the CRL in the OS to verify the new timestamp (Figure 9)

{{IMAGE:9}}

Figure 9: Verifying new CRL timestamp

Finally, we change the local administrator password on the offline root CA and shut it down. Since this is a virtual machine, we can browse on the Hyper-V host to the VM hard drive, mount it, and pull the CRL off of the disk (Figure 10).

{{IMAGE:10}}

Figure 10: Extracting CRL from offline VM hard drive

Note: as per our last blog post, this is not considered secure since anyone with access to the file system of the Hyper-V host, including a threat actor, could perform the exact same action but with the root CA private key, effectively compromising your entire PKI. For the purposes of this blog series and in a non-production lab environment, this practice is overriding security in lieu of convenience. If, however, you have a proper Tier 0 virtualization host and are using an HSM, this could be functional for a production environment with adherence to cybersecurity best practices.

Now we can drop the CRL on the issuing CA and copy it over to the web publishing endpoint (Figure 11).

{{IMAGE:11}}

Figure 11: Copying CRL to issuing CA and web publishing endpoint

This resolves the broken revocation check during startup of the issuing CA and brings the PKI back into the green in PKIView.msc (Figure 12).

{{IMAGE:12}}

Figure 12: PKIView.msc showing healthy PKI status

In this section, we showed one of the common issues arising from an expired CRL and illustrated the importance of maintaining a healthy CRL publishing environment. We also walked through how to resolve this issue by issuing and publishing a new CRL from the root CA.

Delta Certificate Revocation Lists

The IETF RFC 5280 defines a delta certificate revocation list as a CRL that "only lists those certificates, within its scope, whose revocation status has changed since the issuance of a referenced complete [base] CRL."

Delta CRLs are supplemental to the base CRL and allow for a "fresher" certificate revocation list without having to re-publish the base CRL every time a certificate is revoked. Delta CRLs can also help to reduce revocation lookup delays in an environment with particularly large base CRLs, but delta CRLs are functionally rolled up into the base CRL at the next base CRL publishing interval, so they do not provide any advantage over base CRLs with regards to overall size long term.

Delta CRLs are especially useful in high-revocation environments where revocation needs to be respected quickly, as they are published at a more rapid interval than the base CRL. It is important to note, however, that delta CRL publishing intervals are not instantaneous, so a priority revocation such as for a compromised certificate would still require manually re-publishing either the base or delta CRL.

It is critical to understand that delta CRLs are accepted and functional for Windows, but delta CRLs may not be respected by non-Windows systems. Some enterprise distributions of Linux do accept delta CRLs, but you may need to work with your distribution vendor to allow them otherwise. In the case of a CRL lookup by a system without delta CRL support, any certificates in the delta CRL would be overlooked during a CRL lookup in lieu of using the base CRL.

By default, delta CRLs are configured for use in ADCS. When guiding customers, I make the case that unless they anticipate a high revocation load, using delta CRLs is unnecessary. Additionally, if the customer is leveraging non-Windows systems in their environment, I urge caution around delta CRLs to prevent a false sense of security around revocation.

There is nothing inherently wrong with using delta CRLs out of the box but understanding their main purpose (faster revocation publishing out-of-band from the base CRL publishing) is important to drive outcomes. Delta CRLs have a place and are an accepted extension in PKI discussions, but deciding in advance if you will truly leverage their utility goes a long way to reduce administrative overhead of the PKI long term.

If you do not anticipate doing regular revocation, they are an additional administrative touchpoint that will not serve your immediate or long-term needs. If, however, you are concerned about rapid response for revocation or having to manually issue out-of-band CRLs, then delta CRLs can help.

The Authority Information Access Extension

The IETF RFC 3280 defines the Authority Information Access (AIA) extension as "how to access CA information and services for the issuer of the certificate in which the extension appears." This is an extension, similar to the CRL, that is not critical but recommended for the functionality of your PKI.

This location, stamped on every certificate issued by a CA, is used to help end entities construct a valid certificate chain in the event there are any missing or outdated certificates. Without this extension, all certificates in an end entity chain would need to be trusted in advance by the system using the certificate.

The publishing of the AIA location is separate from the CRL, but most PKI implementations use the same publishing endpoint for both. However, it is not necessary to publish to the same location. The AIA location will contain a copy of the public certificate for the root, policy, and issuing CAs in a PKI. You should never publish private keys to this location. The certificates are necessarily accessible by any system. The private key is exactly that: private. It should only exist on the CA itself or, preferably, on an HSM.

The AIA publishing location is part of the CA extension configuration on every ADCS CA (Figure 13) and can also be added to the Online Certificate Status Protocol (OCSP) extension, if desired.

{{IMAGE:13}}

Figure 13: AIA publishing configuration in CA properties

Note the limited options for this configuration. This is by design. You are simply providing a web-based (or LDAP) endpoint to which an endpoint can refer to download additional certificates to build a trust chain.

Publishing certificates to this endpoint is usually a manual process since CA certificate updates are a less frequent operation. It is possible to automate this using something like DFS-R or a scripted process, but that also increases your risk footprint.

It is also important to note that the certificate file name in the publishing location must match exactly the name input into the extension. Any characters, including spaces, beyond what it explicitly declared in the extension will cause the AIA lookup to fail.

A lack of a proper certificate in the AIA location will not generally cause a problem unless an endpoint needs a certificate from the chain. Unlike the CRL, missing AIA information will not cause a CA to not start, and end users will not be warned about missing the CA certificate unless it is necessary to build a chain which might otherwise present as a trust issue vs. a critical error.

If the certificate chain is present in the local system or application trust store, the AIA location is not parsed.

In summary, the AIA location is used to build certificate trust chains. They are often published to the same location as the CRLs and are simply copies of the public certificate for the root, policy, and/or issuing CA servers. This is a non-critical extension, but best practice is to make these available to consumers of your certificates.

Publishing Considerations

The most common question I have heard around CRL and AIA publishing is "what's the best publishing interval?" The answer depends on your organization's use of certificates and how aggressive you are with revocation.

Our standard guidance provided to customers with low revocation and light usage is approximately one (1) year for a base CRL from the root CA. In the event you have to revoke a subordinate CA or policy CA certificate, you will be manually publishing a new CRL along with a new certificate for their replacements, so one (1) year provides a decent window for operation without completely forgetting the root CA exists. This helps to keep processes around root CA maintenance fresh for your administrative teams.

Since issuing CAs are online and can be configured to write the CRL directly to publishing endpoints, a more rapid publishing cadence can be used. I normally recommend anywhere from one (1) week to one (1) month, depending on your anticipated revocation needs.

For AIA publishing, we haven't discussed CA certificate lifetimes yet, but given a standard two-tier PKI validity period of ten (10) years for the root CA and five (5) years for the issuing CA(s), the certificates published to the AIA location will usually be approximately five (5) years and two-and-a-half (2.5) years old, at most, respectively. (More on CA certificate lifetimes in a future blog post.) As a result, AIA publishing will be a manual process (but can be automated, if desired).

Another common question is what protocols to use for publishing. Technically IETF RFC 5280 Section 3.4 defines LDAP, HTTP, FTP, and X.500 for distribution. Out of the box, ADCS, when configured as an enterprise deployment, will define an HTTP and LDAP endpoint for CRL and AIA publishing.

For the purposes of modern security best practice, I advise customers to stick to HTTP for a few reasons:

- HTTP is platform agnostic and acceptable for any network-based platform (Windows, Linux, Mac, mobile devices, network devices, etc.)

- HTTP presents little network overhead compared to LDAP

- Port 80 connectivity is much more palatable to a network security team than allowing communications broadly to port 389

In 15 years of working with ADCS, I have never come across an implementation using FTP. While it is supported as per the specifications, FTP presents a big target for threat actors and should be avoided. I have never seen a pure X.500 distribution configuration.

If you are working in a majority Windows enterprise where everything is domain joined, it could be argued that LDAP is sufficient. LDAP is fault tolerant across all of your AD domain controllers, easily configured from PKIView.msc, endpoints easily managed by group policy, and when configured properly, secure.

However, I do not advise relying solely on LDAP for CRL/AIA distribution, as non-Windows systems in your organization (i.e., network, storage, and virtualization platforms) will likely rely on your PKI and may or may not support LDAP calls for lookups. Additionally, as stated previously, LDAP calls are "expensive" compared to simple HTTP.

When you have a conversation with your network security team about accessibility, you are likely to run into opposition to blanket TCP 389 access for your entire organization. Most enterprises with whom I have worked try to lock down port 389 as much as possible, and if you have a proper tier 0 or network segmentation, opening 389 globally introduces a level of risk I would not advise any organization to endeavor.

If you or your team are insistent on relying on LDAP, I recommend using HTTP as your second option for fault tolerance and platform accessibility.

HTTP is the best route for CRL and AIA publishing. It is fast, reliable, easily extensible using load balancers, and, in an IIS/Windows implementation, it is possible to configure ADCS to write the CRL directly to the file system of a web server(s) for publishing.

It is also natively more secure to just open port 80 to serve up what amount to basic text files vs. opening port 389 to your entire AD infrastructure, allowing access to more than just the published files.

Finally, it is critical to understand that your HTTP publishing endpoint must use port 80. We get the question from time to time about whether or not you can put a certificate in front of the HTTP endpoint to "make it secure."

The problem with that is how are endpoints going to check for revocation of the certificate protecting that web endpoint if the web endpoint uses a certificate with a CRL published to the same location? You will create a loop condition, and the CRL lookup will fail.

Can you put a certificate in front of it? Technically you could, but it would have to be a certificate with a CRL serviced from a different endpoint, likely publicly accessible, which means you are spending money and administrative cycles to maintain a certificate outside of your own PKI which, in my opinion, defeats the purpose of standing up the PKI in the first place.

There is nothing inherently risky about having port 80 open to the specific endpoint, and you can implement security measures on the web server to ensure that a threat actor cannot abuse the web server. All you are serving from that endpoint are some plain text files with information that is necessarily public. There is not anything inherently sensitive in the CRL or AIA that would necessitate protecting the connection with SSL/TLS.

As with many points discussed in this blog, your outcomes may vary. You may have different revocation needs or perhaps you just do not want to deal with booting your root CA annually to do CRL maintenance. For a basic enterprise PKI, the numbers called out in this blog post for publishing intervals should be sufficient to keep things functional without casting aside the need to keep your root CA top-of-mind for your administrative team.

Take the time to discuss your needs with your larger organization and set expectations for regular maintenance of your PKI to ensure it remains functional and secure.

That is all for part 2 of our ADCS blog. In part 3, we are going to start shifting away from the root CA as the primary focus to discuss PKI purpose and common hierarchies.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion