MIT's 10th president James Killian, though not a scientist, orchestrated a landmark Cold War strategy that redirected military technology, intelligence operations, and academic-government collaboration through the groundbreaking Killian Report.

When U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower received alarming intelligence about Soviet nuclear advancements in 1953, he turned to an unlikely strategist: James Killian, the president of MIT who lacked formal scientific training. This decision catalyzed a fundamental shift in Cold War strategy through what became known as the Killian Report—a document that would redirect military technology development, intelligence operations, and the relationship between academia and national defense for decades.

The Strategic Imperative

By 1953, intelligence revealed the USSR had detonated a nuclear bomb years ahead of projections, developed advanced hydrogen bomb technology, and designed bombers rivaling American capabilities. Facing potential nuclear surprise attacks, Eisenhower sought advisors beyond military circles. His selection of Killian—an administrative innovator who'd led MIT's 4,000-person RadLab radar project during WWII—proved pivotal. As David Mindell, MIT's Dibner Professor of History, notes: "Killian turned out to be a truly gifted administrator who understood how to mobilize technical talent toward strategic objectives."

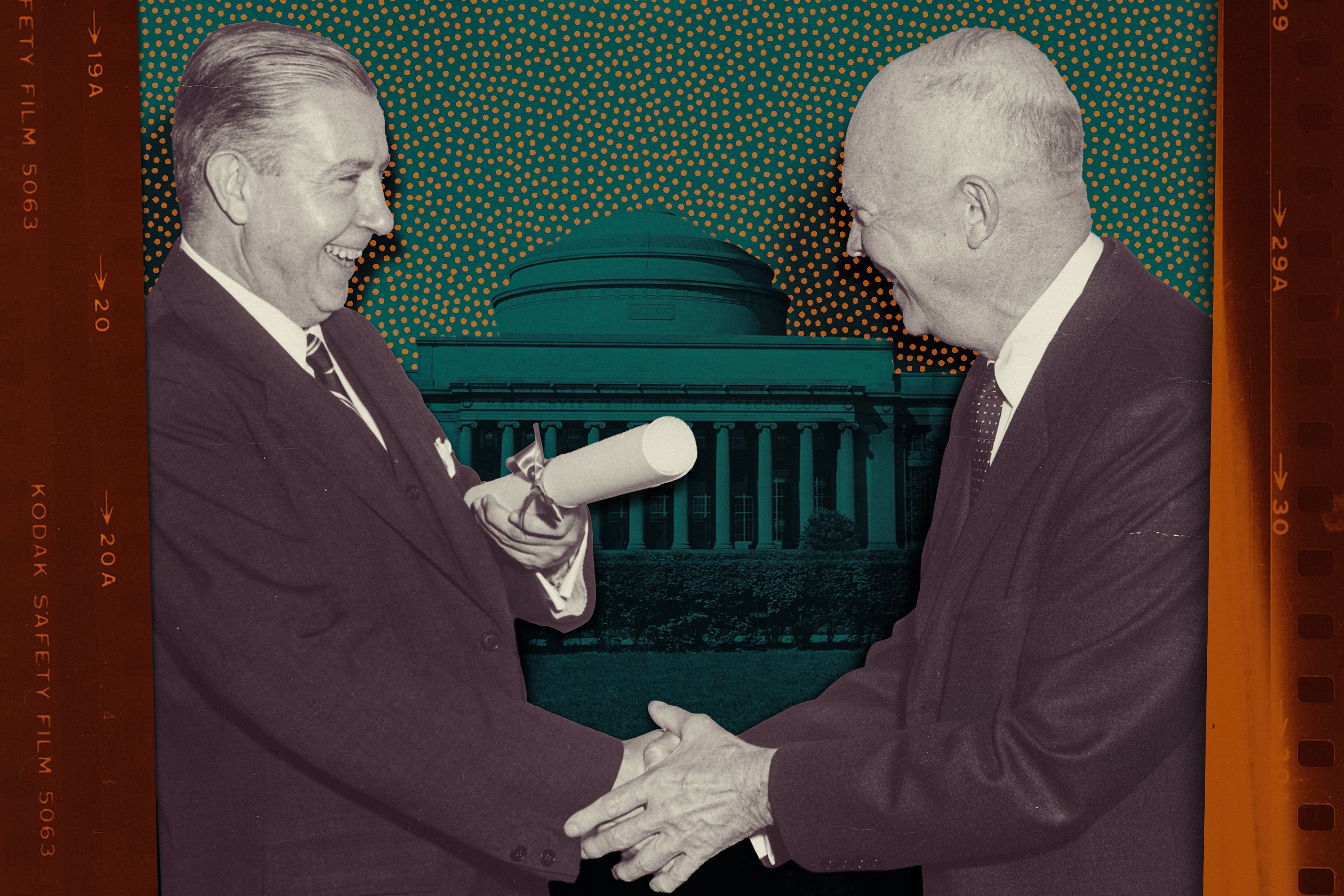

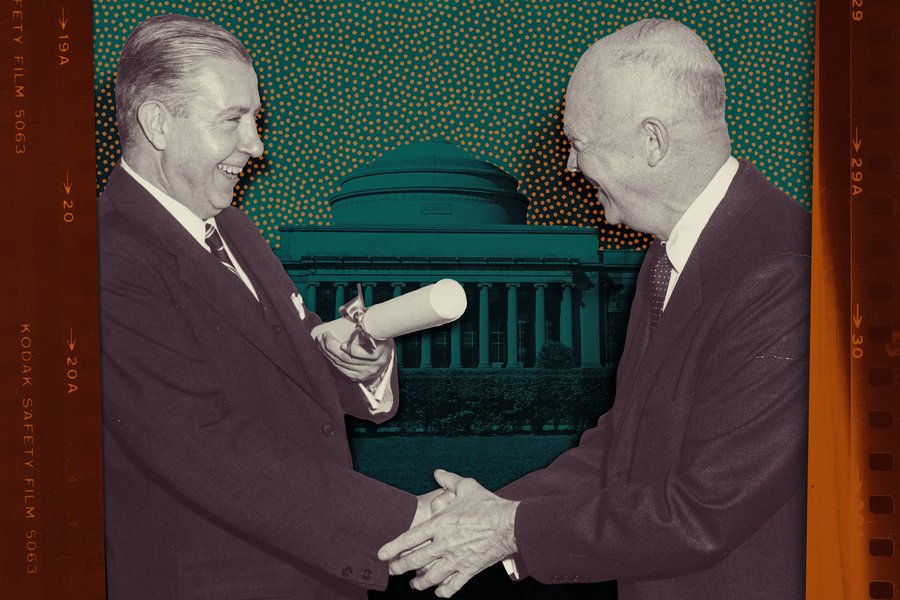

MIT President James Killian with President Eisenhower (circa 1956). Their partnership reshaped Cold War defense policy.

MIT President James Killian with President Eisenhower (circa 1956). Their partnership reshaped Cold War defense policy.

Engineering the Response

Within weeks of Eisenhower's request, Killian convened 42 scientists and engineers into three panels assessing offensive capabilities, continental defense, and intelligence operations. Their 307 meetings across defense agencies produced a 190-page analysis, "Meeting the Threat of Surprise Attack" (1955). The report introduced a four-period framework forecasting the Cold War's technological trajectory:

- 1955-1957: U.S. offensive advantage but high vulnerability

- 1958-1960: Narrowing offensive edge with improved attack anticipation

- Post-1960: Mutual destruction stalemate requiring technological delay tactics

The report made concrete technical recommendations that redirected military R&D:

- Accelerated development of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs)

- High-energy aircraft fuel research

- Radiation hazard modeling from nuclear detonations

- Expanded Arctic monitoring stations via U.S.-Canada cooperation

Intelligence Revolution

Killian's most consequential maneuver was assigning Polaroid founder Edwin Land to lead the intelligence panel. Land's team discovered critical gaps: Military intelligence units couldn't answer basic technical questions about Soviet capabilities. This led to two clandestine projects approved by Eisenhower:

- U-2 Spy Plane: Developed outside traditional military channels to avoid bureaucracy, featuring Land's revolutionary high-altitude imaging systems

- Missile-Firing Submarines: A decade-long project whose propulsion technology later enabled NASA's Apollo missions

The U-2 exemplified the report's technical ambition—providing unprecedented aerial reconnaissance but ultimately damaging Cold War diplomacy when a U-2 was shot down over Russia in 1960.

Complex Legacy

The Killian Report generated lasting impacts with inherent contradictions:

Technical Successes

- Catalyzed ICBM development that defined nuclear deterrence

- Established satellite reconnaissance principles

- Enabled missile submarine technology transferred to NASA's space program

- Forged enduring government-university research partnerships

Structural Ironies

- Eisenhower's warning about the "military-industrial complex" emerged alongside increased militarization of academic research

- Attempts to reduce inter-service rivalries inadvertently intensified them

- Intelligence breakthroughs compromised diplomatic initiatives

Christopher Capozzola, MIT's Elting Morison Professor of History, observes: "The report greased the wheels between MIT scientists and Washington. Universities began orienting their missions toward national interest in unprecedented ways."

The Apollo Guidance Computer developed at MIT. Killian Report submarine propulsion research directly enabled the space program's rocket systems.

The Apollo Guidance Computer developed at MIT. Killian Report submarine propulsion research directly enabled the space program's rocket systems.

Enduring Framework

Killian's influence extended beyond the report. After Sputnik's 1957 launch, Eisenhower appointed him as the first Presidential Science Advisor—a role where he helped establish NASA. MIT's Lincoln Laboratory continues this legacy, advancing technologies from missile defense to secure communications.

Killian's effectiveness stemmed from his approach: "He exemplified that if you want to get something done, don’t take the credit," Capozzola notes. By focusing on actionable technical solutions rather than personal recognition, Killian demonstrated how academically-grounded analysis could reshape national strategy—a model still relevant in today's era of geopolitical competition.

Related Resources

- James R. Killian Papers at MIT Archives

- Lincoln Laboratory current research areas

- Historical analysis: MIT and the Cold War Technological Revolution

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion