In 1915, Japanese engineers faced an unprecedented challenge: designing a railroad car to transport the Yata no Kagami—a sacred mirror embodying the sun goddess—without knowing its weight or dimensions. This is the story of the Kashikodokoro, a uniquely crafted railcar blending Shinto reverence with railway innovation, whose operational secrets endured for decades.

When Japan's Imperial Household needed to transport the Yata no Kagami—one of the Three Sacred Treasures central to the Emperor's enthronement—from Tokyo to Kyoto in 1915, railway engineers confronted a profound technical and cultural dilemma. The sacred mirror, believed to house the spirit of the sun goddess Amaterasu, couldn't be touched, weighed, or even fully examined by the designers. The resulting solution: the Kashikodokoro Riding Car, a specialized railcar representing a remarkable fusion of Shinto tradition and early 20th-century engineering.

The Impossible Design Brief

Faced with restrictions forbidding physical inspection, engineers from the Japanese Ministry of Railways Oi works relied on historical records to estimate the mirror's weight. Chronicles from 1868 described sixteen men straining to carry the mirror-litter along the Tōkaidō road. Using this anecdotal data, the team made conservative weight calculations, designing structural supports and stabilization systems for a load far heavier than anticipated. The car's frame, bogies, and braking system (a vacuum brake) were engineered for absolute stability and minimal vibration.

Sacred Architecture on Rails

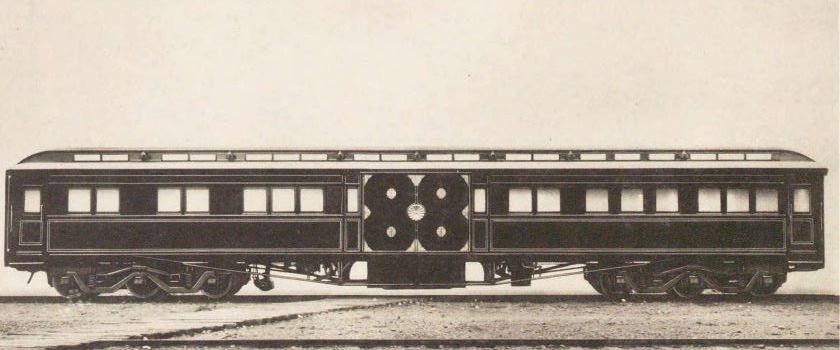

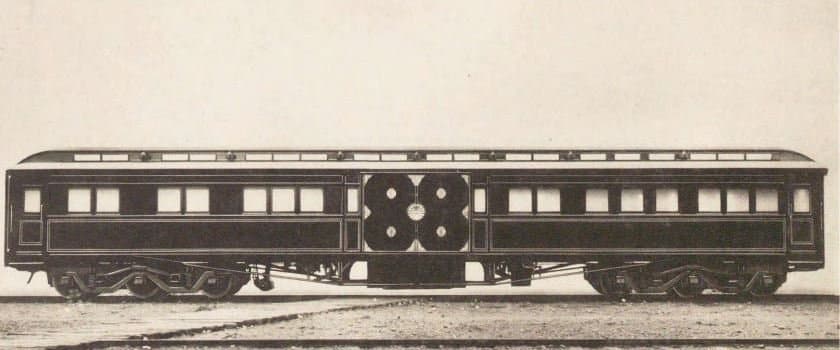

Measuring 19.75 meters long and weighing 31.49 tons, the car's interior was a masterpiece of traditional craftsmanship:

- Mirror Sanctum (Room 4): Constructed primarily of unpainted hinoki (Japanese cypress) with gold-plated fittings and a coffered ceiling in Shinden-zukuri style. Wide folding doors (2.4 meters) allowed the mirror's placement, later sealed with chrysanthemum emblems.

- Attendant Quarters: Six other rooms housed attendants in spaces paneled with oak and sawtooth oak, featuring maple ceilings and teak window frames. A dedicated rear corridor allowed movement without intruding on the sacred space.

- Ritual Details: Even the toilet featured black lacquer exterior and vermilion interior, with a white wooden ladle, reflecting ceremonial purity standards.

Operational Secrecy and Legacy

The Kashikodokoro saw only four operational journeys: round trips for the enthronements of Emperor Taishō (1915) and Emperor Shōwa (1928). Its use demanded extreme secrecy; transfer procedures were rehearsed meticulously, with trial runs conducted at Tokyo, Nagoya, and Osaka stations throughout 1928. Decommissioned in 1959 after legal changes moved enthronements to Tokyo, the car was stored under tight security. As recently as 2023, its relocation ahead of depot demolition was kept confidential, underscoring its enduring significance.

Why it matters for engineers: The Kashikodokoro represents a pinnacle of bespoke problem-solving under unique constraints. It forced innovation in weight estimation, vibration damping, and culturally sensitive design—long before computational modeling existed. Its preservation (reportedly still emanating the scent of cypress decades later, per Railway Journal 1982) offers a tangible link to an era where engineering served equally profound technical and spiritual imperatives. While modern tech grapples with digital sacred cows, the Kashikodokoro reminds us that some of history's most fascinating engineering challenges emerged at the intersection of tradition and transit.

{{IMAGE:2}}

Source: Adapted from Wikipedia content on the Kashikodokoro Riding Car (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion