A former GCHQ technician's rediscovery of a custom 8051 assembler written in Turbo Pascal in 1984 reveals the ingenuity of early embedded development and the enduring power of retro computing.

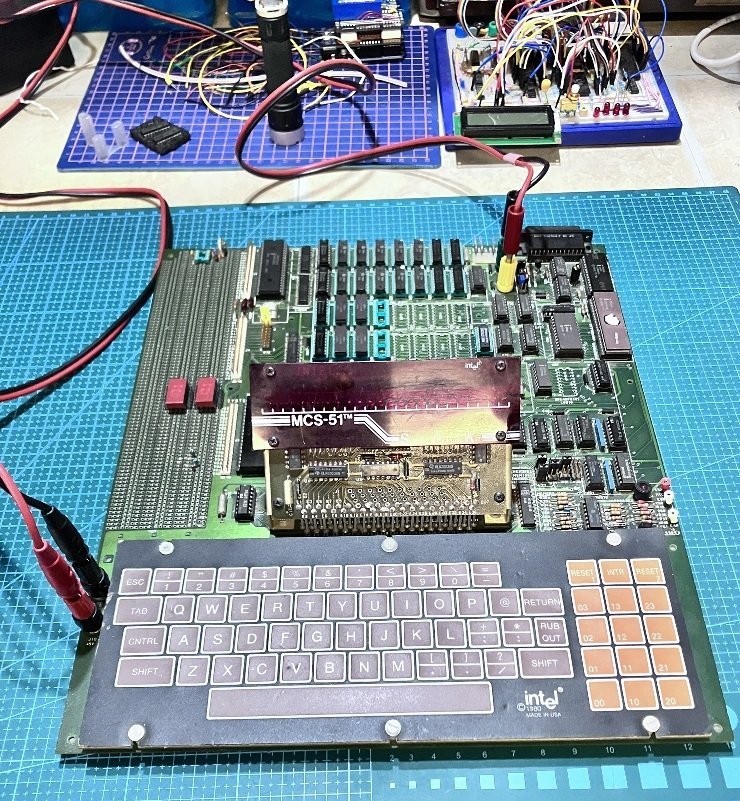

The dusty archives of GCHQ occasionally yield more than just secrets. In a recent email from a former colleague, Tony Partington, a piece of computing history emerged: an Intel 8051 developer's board, quietly salvaged from a disposal pile in the late 1990s. This relic, part of an extremely expensive kit once used by the UK's signals intelligence agency, has sparked a journey back to the early 1980s—a time when adding intelligence to electronics was a feat of both engineering and ingenuity.

For the author, then a 20-year-old electronics technician at GCHQ, the 8051 was more than just a microcontroller; it was a gateway to a new world of embedded design. In the mid-1980s, the world of microcomputers—dominated by the Z80, 680x, and 650x families—was hobbyist-friendly. Microcontrollers, however, were largely confined to industrial applications. The Intel 8051, with its 2KB of ROM and 128 bytes of RAM, was a powerhouse of its day, but its development tools were prohibitively expensive. A single 8051 chip cost about $40 (equivalent to $90 today), and that was just the beginning. Assemblers, compilers, and EPROM programmers added hundreds, if not thousands, of dollars to the bill.

Working in a maintenance department focused on repairing DEC PDP-11/70s, the author and his colleagues had access to a PC/XT, an EPROM programmer, and a nearly infinite supply of components—but not the full Intel development suite. The VAX/VMS-based tools were out of reach. This constraint, however, became a catalyst for innovation. "Being perpetually broke," the author recalls, "forking out mega-bucks for the above was never going to happen." Instead, he turned to what he had: a PC, Turbo Pascal 1.0, and a desire to build.

The result was a custom assembler for the 8051, written entirely in Turbo Pascal. "I had never done any formal programming courses, had never used an assembler, nor had any idea how an assembler worked until I decided to build one," the author admits. The process was a masterclass in bootstrap engineering: he designed a simple assembly language syntax, inspired by BASIC and hand-coded listings from computer magazines, and then built a tool to translate it into the 8051's hexadecimal opcodes. The assembler supported labels for memory locations and jumps, mimicking the workflow of hand-coding but automating the tedious translation.

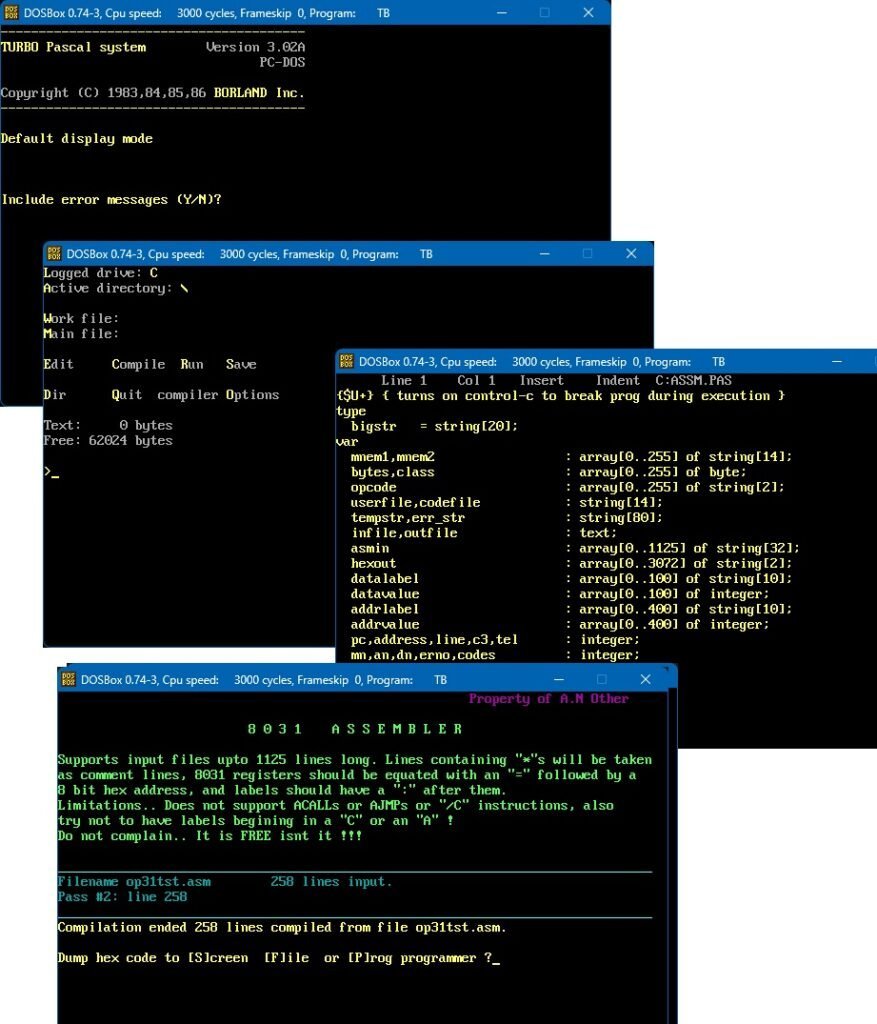

The 660 lines of Pascal, compiled into a 24KB executable, were a marvel of constrained design. The 8051's minuscule memory footprint meant every byte counted. "The code is laughable (from the perspective of 2025 Boz)," the author notes, "but I had to remember that back then Turbo Pascal compiled to the old COM style executable, not the EXE, and so code and data had to fit into a 64KB memory segment." The assembler also included an interface to the EPROM programmer, allowing for seamless burning of chips. It was a complete, self-contained development environment built from scratch.

This tool wasn't just an academic exercise. The author used it to program an 8031-based central heating controller, a project that combined his professional skills with his passion for building. The success of the assembler even inspired a colleague to write a Z80 version. And now, four decades later, the code survives. Tony Partington preserved the source code and the original Turbo Pascal 3.02 IDE, and in 2025, it still runs perfectly under DOSBox.

The preservation of this code is more than a nostalgic artifact; it's a testament to the era of "roll-your-own" tools. Before the ubiquity of open-source and the internet, developers often built their own solutions to bridge gaps in commercial offerings. The author's assembler, born from necessity and curiosity, embodies the hacker spirit that would later fuel the free software movement. It also highlights the importance of sharing and preserving these artifacts, as they offer invaluable lessons in resourcefulness and design.

The story of the 8051 assembler is a reminder that innovation often flourishes at the intersection of constraint and creativity. For today's developers, accustomed to vast libraries and cloud-based toolchains, it's a humbling look back at a time when every kilobyte and every clock cycle mattered. And for the author, the rediscovery of this code is a "trip down memory lane" that connects his past as a junior technician to his present as an author and technologist. As he reflects on the 55KB project file that contains the assembler, the IDE, and a wealth of memories, one can't help but wonder what other forgotten tools and tales are waiting to be unearthed from the archives of computing history.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion