Thirteen years after the Higgs boson discovery, particle physics faces existential questions as the Large Hadron Collider finds no new fundamental particles, forcing physicists to confront funding challenges, brain drain to AI, and debates about future multibillion-dollar colliders.

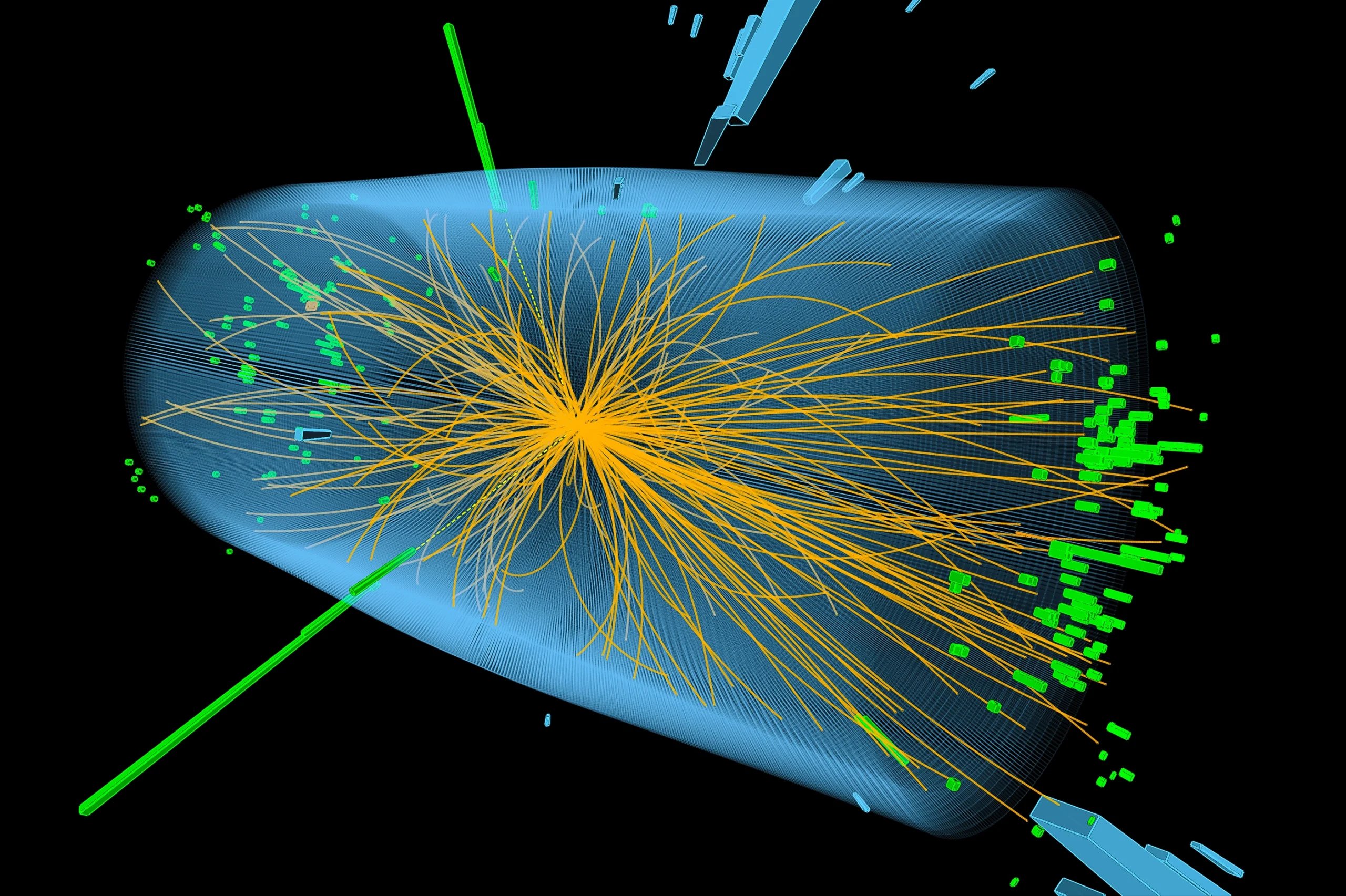

In July 2012, physicists at the Large Hadron Collider announced the discovery of the Higgs boson—the final piece of the Standard Model of particle physics. This monumental achievement unexpectedly triggered a crisis: despite smashing protons together at unprecedented energies, no new particles or forces beyond the Standard Model emerged. The absence of "new physics" left foundational questions unanswered: What comprises dark matter? Why does matter dominate antimatter? And how to resolve the staggering mass disparity between the Higgs boson and the quantum gravity scale?

The Disappearing Roadmap

For decades, theorists like Edward Witten proposed solutions to these puzzles, predicting undiscovered particles slightly heavier than the Higgs. The LHC was designed to find them. Its failure to do so dismantled physics' theoretical compass. Adam Falkowski, a Paris-based physicist, predicted in 2012 that without experimental guidance, particle physics would enter "slow decay." Today, he observes a brain drain: "If you want to change the world now, you will do AI; you will do something different from particle physics." Jared Kaplan, a former physicist who co-founded AI company Anthropic, confirms this shift: "AI was going to make progress faster than almost any field in science historically."

Hunting in Hidden Valleys

Despite the setbacks, the LHC continues operating with upgraded AI systems that analyze collision debris with unprecedented precision. These tools measure scattering amplitudes—probabilities of particle interactions—to hunt for subtle statistical deviations that might hint at lightweight unknown particles. "There’s a huge amount of unexplored territory there," says Harvard physicist Matt Strassler, who suspects new physics might manifest in low-energy "hidden valleys," such as unstable dark matter particles decaying into excess muon pairs.

The Collider Conundrum

The field now pins hopes on next-generation machines. CERN proposes a €15 billion Future Circular Collider (FCC), a 91-kilometer ring beneath Switzerland and France. Its electron-collision phase would probe indirect signals of new physics, while later proton collisions could reach seven times the LHC’s energy—though with no guarantee of discoveries. Meanwhile, U.S. physicists advocate for a muon collider, leveraging heavier particles for cleaner, high-energy collisions. Maria Spiropulu of Caltech notes the technical challenge: "We have to figure out how to do it in between 10 and 20 billion [dollars]." Both projects face skepticism given the lack of experimental hints.

A Field Redefined

Cari Cesarotti, a CERN theorist, counters narratives of doom: "Particle physics isn’t dead; it’s just hard." Yet she acknowledges a self-fulfilling prophecy—talented researchers avoid the field due to perceived stagnation. Falkowski now studies scattering amplitude geometries, seeking patterns that might reveal deeper truths about quantum gravity. Others explore alternatives: thorium-229 decay experiments to detect varying fundamental constants, or searches for axion dark matter.

The AI Wildcard

AI’s role remains contested. While Kaplan believes AI could soon generate theoretical physics papers "as good as [those by] Nima Arkani-Hamed or Ed Witten," Cesarotti warns against overreliance: "AI is making people worse at physics. What we need is humans to sit down and think of new solutions." The uncertainty persists, but Strassler offers perspective: "It was easy for 125 years. One thing led to the next. That lucky century has, for now, come to an end."

The quest continues—without guarantees. As experimental avenues narrow and theoretical imagination strains, particle physics confronts a sobering possibility: humanity may already possess all empirical clues to nature’s deepest secrets.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion