Popular medieval city-building games like 'Settlers' and 'Anno' perpetuate myths about organic village growth and simplistic economies, overlooking planned settlements, feudal taxes, and environmental threats—but incorporating historical accuracy could redefine the genre.

Medieval city-builder games have captivated players for decades with their charming depictions of village life, resource management, and gradual expansion. Titles like Settlers (1993), Knights and Merchants (1998), and the Anno series present a world where settlements grow organically from humble beginnings into thriving towns. Yet this growth-centric model fundamentally misrepresents medieval European societies, where stability—not expansion—was the norm due to harsh environmental, economic, and political constraints.

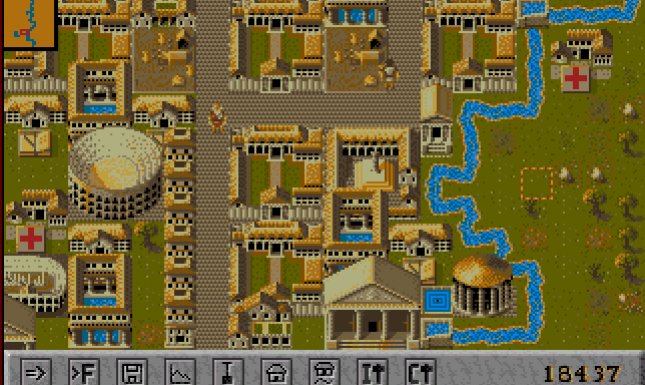

Screenshot: Caesar (1992), an early city-builder influencing medieval-themed games.

Screenshot: Caesar (1992), an early city-builder influencing medieval-themed games.

Historical evidence reveals medieval villages were carefully planned, not organic sprawls. Archaeologists identify distinct settlement patterns—like circular manors (vroonhoeve) with radial field layouts or street-aligned farms exploiting fenlands—designed by monasteries or feudal lords. Colonizers cleared land through coordinated burns (brant) or cuts (rode), with surveyors demarcating plots using hedges, ditches, and roads. Water access was critical but risky, as floods could fertilize meadows or destroy harvests.

Games simplify village management, ignoring complex socio-economic layers. Actual medieval life involved crop rotation systems (like the three-field method), communal grazing, and relentless resource extraction by lords and clergy. Tithes and taxes consumed up to half of a village's yield, collected during seasonal events absent from games. Threats were omnipresent: droughts, livestock plagues, and warfare could decimate populations. Banished (2014) partially acknowledges this fragility with its high mortality mechanics, but still frames survival as a path toward growth.

Screenshot: Settlers (1993) showing production chains—historically overshadowed by feudal obligations.

Screenshot: Settlers (1993) showing production chains—historically overshadowed by feudal obligations.

Four innovations could bridge this accuracy gap while enhancing gameplay:

- Initial Planning Phase: Let players design settlements using historical templates (e.g., street villages or hybrid layouts) before growth begins, rewarding adaptation to terrain.

- Flexible Infrastructure Tools: Adopt Cities: Skylines' freeform roads to create ditches, enclosures, and curved paths, moving beyond grids.

- Environmental Systems: Model floodplains as double-edged resources, as seen in historical Egypt-centric games like Children of the Nile.

- Feudal Mechanics: Visualize tax collectors assessing sheaves or seizing livestock, making resource loss a narrative element rather than abstract deductions.

Screenshot: Knights and Merchants (1998) depicting warfare's devastation—a real threat omitted from economic models.

Screenshot: Knights and Merchants (1998) depicting warfare's devastation—a real threat omitted from economic models.

Current design conventions prioritize player satisfaction: linear growth feels rewarding, and grid systems simplify pathfinding. Yet tools now exist to tackle complex layouts, and rising interest in historical authenticity (evident in mods for Cities: Skylines recreating medieval Croatia) signals market readiness. Integrating land surveys, tithes, or flood management wouldn't just educate—it could create compelling tensions between survival and loyalty, enriching a genre ripe for innovation.

For developers, the opportunity lies in challenging romanticized medieval tropes. Windmills and castles attract players, but nuanced systems reflecting crop rotation or seigneurial courts could deepen immersion. As studios explore fresh settings—from West African kingdoms to Byzantine trade networks—medieval Europe's documented intricacies offer a blueprint for turning historical constraints into engaging mechanics.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion