MIT researchers have developed a miniaturized ultrasound system that could make frequent breast cancer screening more accessible, potentially detecting tumors earlier in high-risk patients.

For people at high risk of developing breast cancer, frequent screenings with ultrasound can help detect tumors early. MIT researchers have now developed a miniaturized ultrasound system that could make it easier for breast ultrasounds to be performed more often, either at home or at a doctor's office.

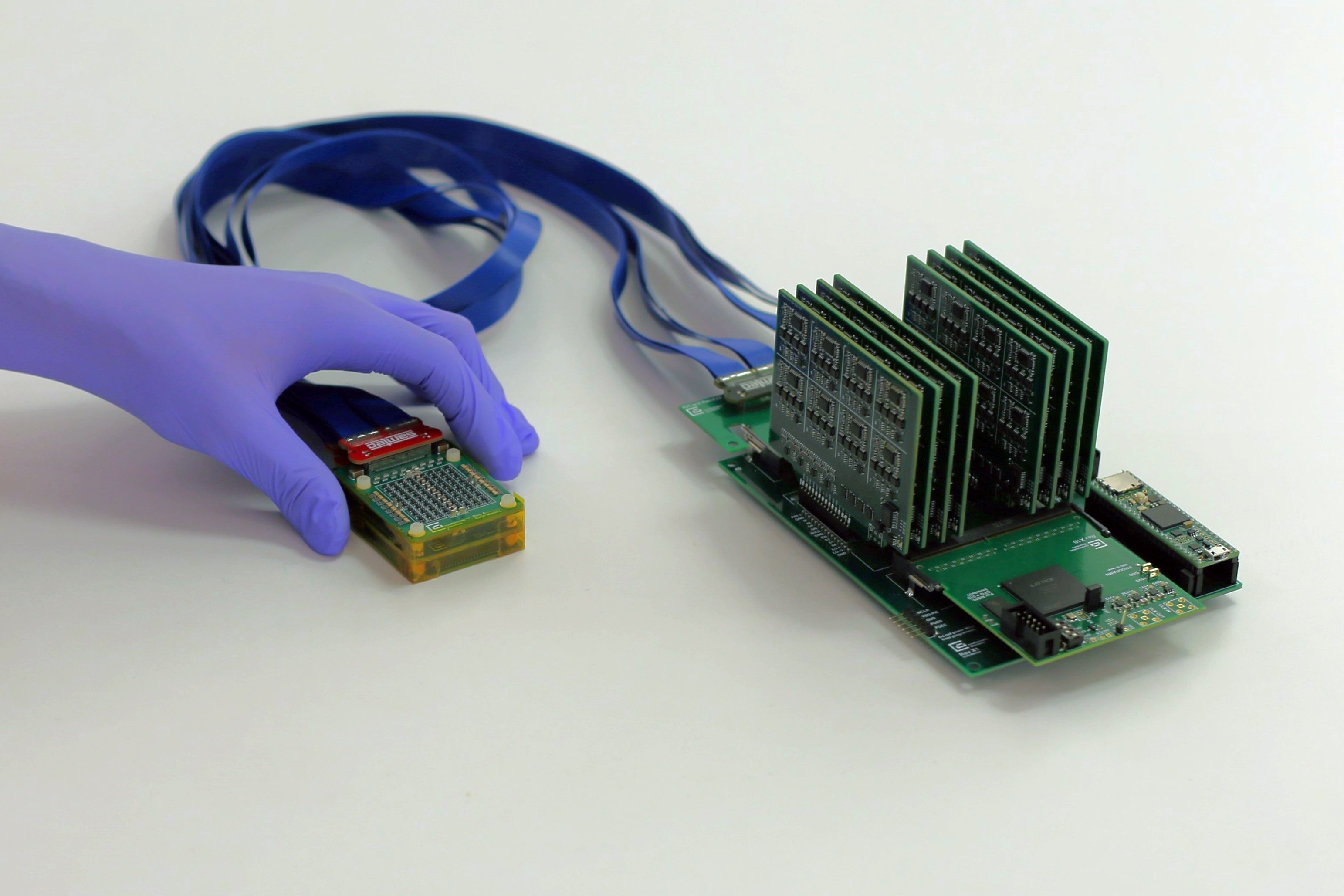

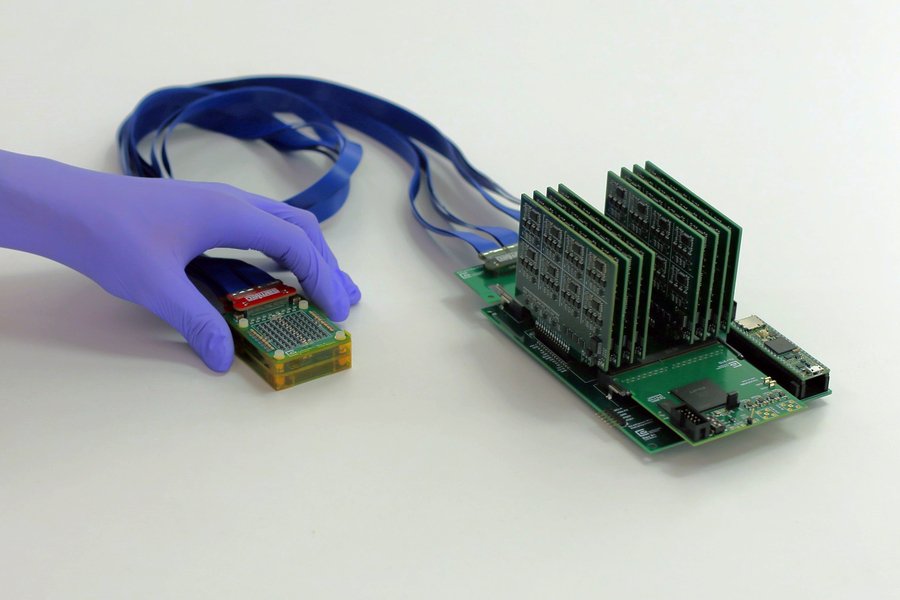

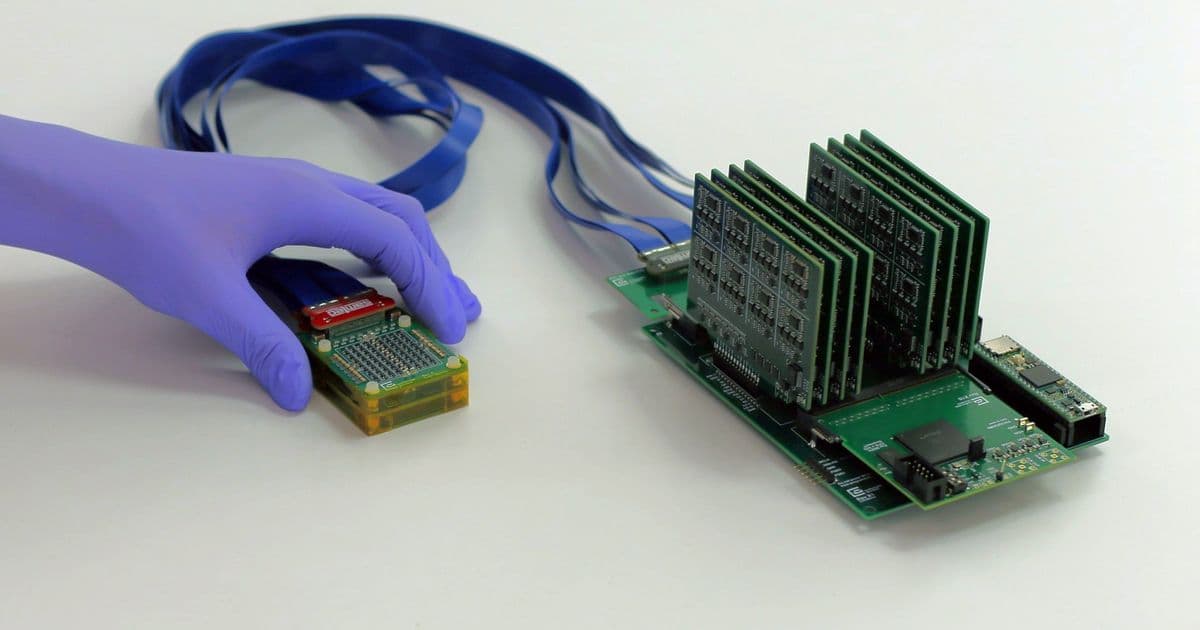

The new system consists of a small ultrasound probe attached to an acquisition and processing module that is a little larger than a smartphone. This system can be used on the go when connected to a laptop computer to reconstruct and view wide-angle 3D images in real-time.

"Everything is more compact, and that can make it easier to be used in rural areas or for people who may have barriers to this kind of technology," says Canan Dagdeviren, an associate professor of media arts and sciences at MIT and the senior author of the study. "With this system, she says, more tumors could potentially be detected earlier, which increases the chances of successful treatment."

Colin Marcus PhD '25 and former MIT postdoc Md Osman Goni Nayeem are the lead authors of the paper, which appears in the journal Advanced Healthcare Materials. Other authors of the paper are MIT graduate students Aastha Shah, Jason Hou, and Shrihari Viswanath; MIT summer intern and University of Central Florida undergraduate Maya Eusebio; MIT Media Lab Research Specialist David Sadat; MIT Provost Anantha Chandrakasan; and Massachusetts General Hospital breast cancer surgeon Tolga Ozmen.

The Challenge of Interval Cancers

While many breast tumors are detected through routine mammograms, which use X-rays, tumors can develop in between yearly mammograms. These tumors, known as interval cancers, account for 20 to 30 percent of all breast cancer cases, and they tend to be more aggressive than those found during routine scans.

Detecting these tumors early is critical: When breast cancer is diagnosed in the earliest stages, the survival rate is nearly 100 percent. However, for tumors detected in later stages, that rate drops to around 25 percent.

For some individuals, more frequent ultrasound scanning in addition to regular mammograms could help to boost the number of tumors that are detected early. Currently, ultrasound is usually done only as a follow-up if a mammogram reveals any areas of concern. Ultrasound machines used for this purpose are large and expensive, and they require highly trained technicians to use them.

"You need skilled ultrasound technicians to use those machines, which is a major obstacle to getting ultrasound access to rural communities, or to developing countries where there aren't as many skilled radiologists," Viswanath says.

By creating ultrasound systems that are portable and easier to use, the MIT team hopes to make frequent ultrasound scanning accessible to many more people.

Evolution of the Technology

In 2023, Dagdeviren and her colleagues developed an array of ultrasound transducers that were incorporated into a flexible patch that can be attached to a bra, allowing the wearer to move an ultrasound tracker along the patch and image the breast tissue from different angles. Those 2D images could be combined to generate a 3D representation of the tissue, but there could be small gaps in coverage, making it possible that small abnormalities could be missed.

Also, that array of transducers had to be connected to a traditional, costly, refrigerator-sized processing machine to view the images.

In their new study, the researchers set out to develop a modified ultrasound array that would be fully portable and could create a 3D image of the entire breast by scanning just two or three locations.

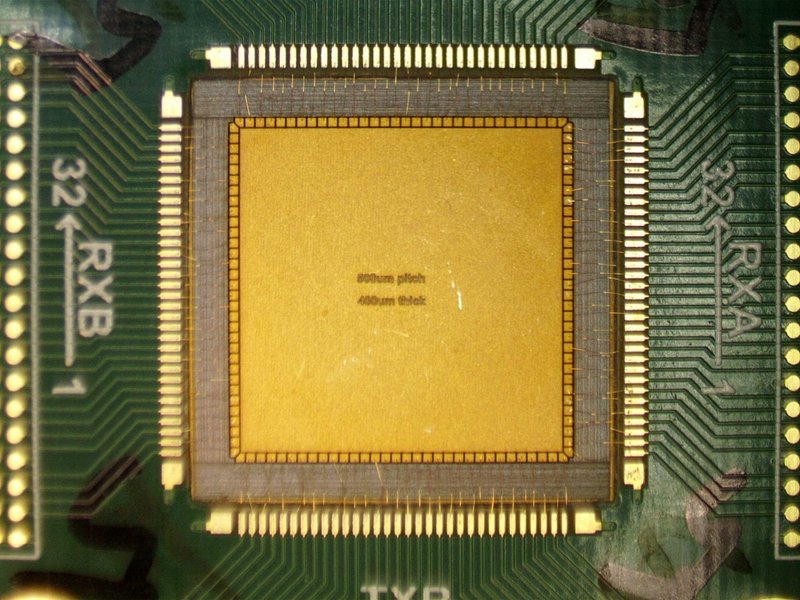

The new system they developed is a chirped data acquisition system (cDAQ) that consists of an ultrasound probe and a motherboard that processes the data. The probe, which is a little smaller than a deck of cards, contains an ultrasound array arranged in the shape of an empty square, a configuration that allows the array to take 3D images of the tissue below.

This data is processed by the motherboard, which is a little bit larger than a smartphone and costs only about $300 to make. All of the electronics used in the motherboard are commercially available. To view the images, the motherboard can be connected to a laptop computer, so the entire system is portable.

"Traditional 3D ultrasound systems require power expensive and bulky electronics, which limits their use to high-end hospitals and clinics," Chandrakasan says. "By redesigning the system to be ultra-sparse and energy-efficient, this powerful diagnostic tool can be moved out of the imaging suite and into a wearable form factor that is accessible for patients everywhere."

This system also uses much less power than a traditional ultrasound machine, so it can be powered with a 5V DC supply (a battery or an AC/DC adapter used to plug in small electronic devices such as modems or portable speakers).

"Ultrasound imaging has long been confined to hospitals," says Nayeem. "To move ultrasound beyond the hospital setting, we reengineered the entire architecture, introducing a new ultrasound fabrication process, to make the technology both scalable and practical."

Testing and Future Development

The researchers tested the new system on one human subject, a 71-year-old woman with a history of breast cysts. They found that the system could accurately image the cysts and created a 3D image of the tissue, with no gaps. The system can image as deep as 15 centimeters into the tissue, and it can image the entire breast from two or three locations.

And, because the ultrasound device sits on top of the skin without having to be pressed into the tissue like a typical ultrasound probe, the images are not distorted.

"With our technology, you simply place it gently on top of the tissue and it can visualize the cysts in their original location and with their original sizes," Dagdeviren says.

The research team is now conducting a larger clinical trial at the MIT Center for Clinical and Translational Research and at MGH. The researchers are also working on an even smaller version of the data processing system, which will be about the size of a fingernail. They hope to connect this to a smartphone that could be used to visualize the images, making the entire system smaller and easier to use.

They also plan to develop a smartphone app that would use an AI algorithm to help guide the patient to the best location to place the ultrasound probe.

While the current version of the device could be readily adapted for use in a doctor's office, the researchers hope that the future, a smaller version can be incorporated into a wearable sensor that could be used at home by people at high risk for developing breast cancer.

Dagdeviren is now working on launching a company to help commercialize the technology, with assistance from an MIT HEALS Deshpande Momentum Grant, the Martin Trust Center for MIT Entrepreneurship, and the MIT Media Lab WHx Women's Health Innovation Fund.

The research was funded by a National Science Foundation CAREER Award, a 3M Non-Tenured Faculty Award, the Lyda Hill Foundation, and the MIT Media Lab Consortium.

This development represents a significant step toward democratizing access to advanced medical imaging technologies, potentially enabling earlier detection of breast cancer for millions of people who currently face barriers to frequent screening.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion