MIT physicists have developed a breakthrough terahertz microscope that overcomes the fundamental diffraction limit, allowing them to observe quantum vibrations in superconducting materials for the first time. The new technique could accelerate the search for room-temperature superconductors and enable future terahertz-based wireless communications.

Physicists at MIT have achieved a major breakthrough in microscopy by developing a terahertz microscope capable of observing quantum-scale phenomena in superconducting materials—a feat previously thought impossible due to fundamental physical limitations.

Overcoming the Terahertz Diffraction Barrier

The challenge was formidable. Terahertz light, which oscillates over a trillion times per second and sits between microwaves and infrared radiation on the electromagnetic spectrum, has wavelengths hundreds of microns long. This makes it fundamentally unsuitable for imaging microscopic structures, as the diffraction limit restricts spatial resolution to roughly the wavelength of the radiation used.

"Our main motivation is this problem that, you might have a 10-micron sample, but your terahertz light has a 100-micron wavelength, so what you would mostly be measuring is air, or the vacuum around your sample," explains Alexander von Hoegen, a postdoc in MIT's Materials Research Laboratory and lead author of the study.

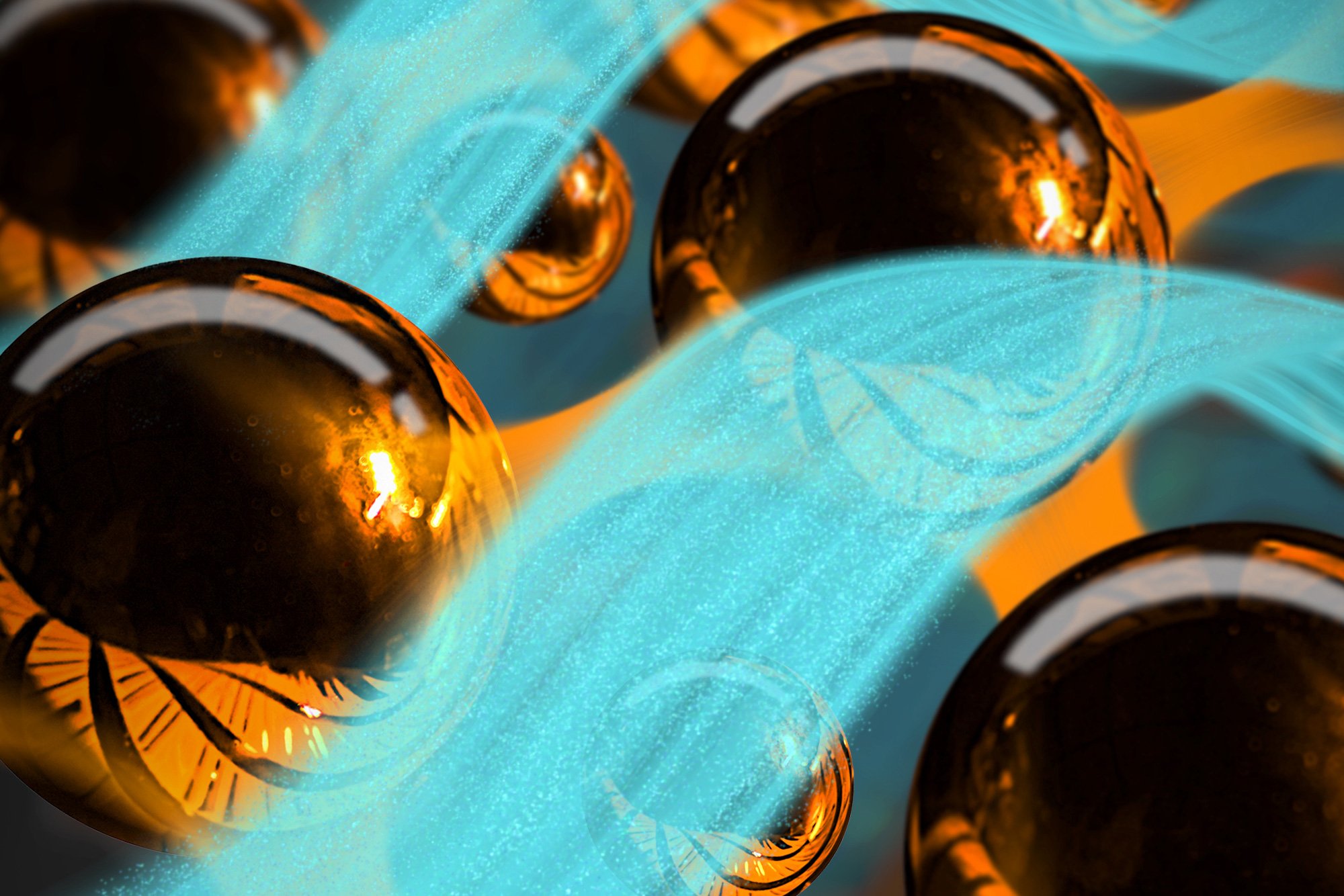

To solve this problem, the team turned to spintronic emitters—a recent technology that produces sharp pulses of terahertz light. These emitters are made from multiple ultrathin metallic layers. When a laser illuminates the multilayered structure, it triggers a cascade of effects in the electrons within each layer, ultimately emitting a pulse of energy at terahertz frequencies.

By holding a sample extremely close to the emitter, the team trapped the terahertz light before it had a chance to spread, essentially squeezing it into a space much smaller than its wavelength. This approach allowed the light to bypass the diffraction limit and resolve features previously too small to see.

The researchers enhanced this technique by interfacing the spintronic emitters with a Bragg mirror—a multilayered structure of reflective films that successively filters out certain, undesired wavelengths of light while letting through others, protecting the sample from the "harmful" laser which triggers the terahertz emission.

Observing Superconducting Electrons in Motion

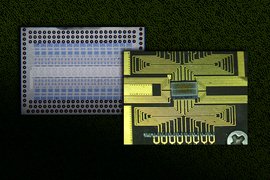

As a demonstration, the team used their new microscope to image a small, atomically thin sample of bismuth strontium calcium copper oxide, or BSCCO—a material that superconducts at relatively high temperatures. They placed the sample very close to the terahertz source and imaged it at temperatures close to absolute zero—cold enough for the material to become a superconductor.

To create the image, they scanned the laser beam, sending terahertz light through the sample and looking for the specific signatures left by the superconducting electrons. "We see the terahertz field gets dramatically distorted, with little oscillations following the main pulse," von Hoegen says. "That tells us that something in the sample is emitting terahertz light, after it got kicked by our initial terahertz pulse."

Through further analysis, the team concluded that the terahertz microscope was observing the natural, collective terahertz oscillations of superconducting electrons within the material. "It's this superconducting gel that we're sort of seeing jiggle," von Hoegen describes.

This jiggling superfluid was expected theoretically but had never been directly visualized until now. The observation represents a fundamental advance in our ability to study quantum materials.

Implications for Future Technologies

The implications of this breakthrough extend far beyond basic physics research. By using terahertz light to probe BSCCO and other superconductors, scientists can gain a better understanding of properties that could lead to long-coveted room-temperature superconductors.

Additionally, the new microscope can help identify materials that emit and receive terahertz radiation. Such materials could be the foundation of future wireless, terahertz-based communications that could potentially transmit more data at faster rates compared to today's microwave-based communications.

"There's a huge push to take Wi-Fi or telecommunications to the next level, to terahertz frequencies," von Hoegen notes. "If you have a terahertz microscope, you could study how terahertz light interacts with microscopically small devices that could serve as future antennas or receivers."

The Unique Promise of Terahertz Technology

Terahertz light occupies a unique spectral "sweet spot" that makes it particularly promising for various applications. Like microwaves, radio waves, and visible light, terahertz radiation is nonionizing and therefore does not carry enough energy to cause harmful radiation effects, making it safe for use in humans and biological tissues.

At the same time, much like X-rays, terahertz waves can penetrate a wide range of materials, including fabric, wood, cardboard, plastic, ceramics, and even thin brick walls. Owing to these distinctive properties, terahertz light is being actively explored for applications in security screening, medical imaging, and wireless communications.

Looking Forward

The MIT team is now applying the microscope to other two-dimensional materials, where they hope to capture more terahertz phenomena. "There are a lot of the fundamental excitations, like lattice vibrations and magnetic processes, and all these collective modes that happen at terahertz frequencies," von Hoegen says. "We can now resonantly zoom in on these interesting physics with our terahertz microscope."

This research, published today in the journal Nature, was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy and by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. The breakthrough represents a significant advance in our ability to observe and understand quantum materials, potentially accelerating progress toward transformative technologies like room-temperature superconductors and ultra-fast wireless communications.

The work demonstrates how creative engineering solutions can overcome fundamental physical limitations, opening entirely new windows into the quantum world. As terahertz technology continues to develop, this microscope could become an essential tool for materials scientists and physicists exploring the frontiers of quantum phenomena.

Paper: Imaging a terahertz superfluid plasmon in a two-dimensional superconductor (Check for open access version)

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion