Inspired by the molecular design of explosives like TNT, researchers propose integrating anodes, cathodes, and separators into single polymer chains to create ultra-compact batteries. This approach could achieve 100x higher power density and near-infinite cycle life compared to traditional lithium-ion cells, though significant synthesis hurdles remain. The concept represents a radical shift in electrochemical storage, targeting applications where speed and longevity outweigh raw energy density.

Imagine a battery that harnesses the same molecular principles as TNT—not to detonate, but to deliver unprecedented bursts of power. That’s the provocative idea explored by Ian McKay of Orca Sciences, who argues that today’s electrochemical batteries are fundamentally limited by their layered, mechanical construction. Just as early gunpowder mixed coarse grains of charcoal and saltpeter, modern batteries keep anodes and cathodes microns apart, forcing ions through sluggish journeys across separators. But what if these components could be integrated at the angstrom scale, with redox groups bonded directly onto a single polymer chain? The result could be thin-film power sources with power densities dwarfing today’s best cells—though the path there is fraught with chemical complexity.

The Explosive Analogy: From Gunpowder to Molecular Revolution

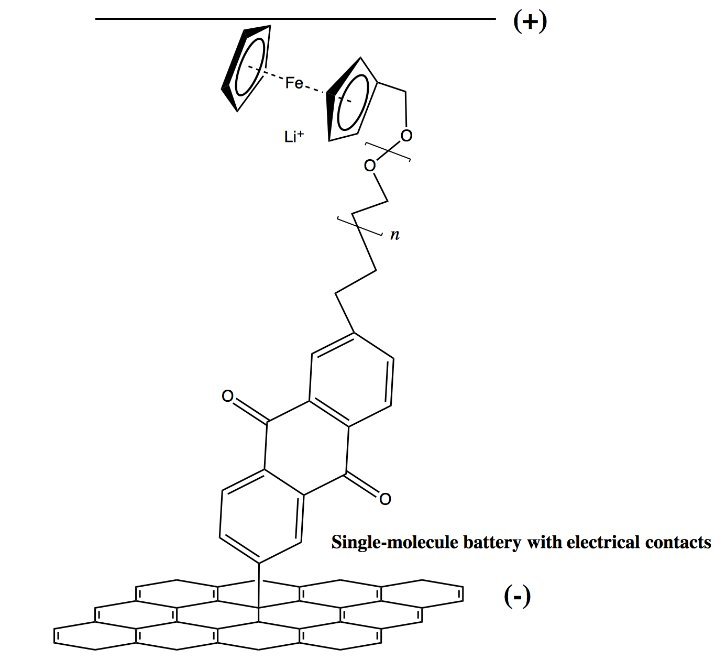

McKay draws a compelling parallel to explosives history. Pre-1845 mixtures like gunpowder achieved deflagration speeds of ~100 m/s by blending oxidizers and reducers as separate particles. The leap to compounds like TNT—where oxidizing (NO₂) and reducing (carbon) groups sit just 1.5 angstroms apart on the same molecule—boosted velocities to 10,000 m/s. Similarly, batteries suffer from ‘chemical distance’: even a 20-micron separator creates a marathon for ions, throttling power output. By covalently bonding anode and cathode functionalities to an ion-conducting polymer backbone, reactions could occur orders of magnitude faster. For instance, a ferrocene (reducer) and anthraquinone (oxidizer) linked by polyethylene oxide (PEO) would create a ‘single-electron charge pump’ with minimal ion travel.

A Proof of Concept: Synthesis Challenges and Promise

McKay outlines a viable synthesis path for such a molecular battery, though it demands precision chemistry:

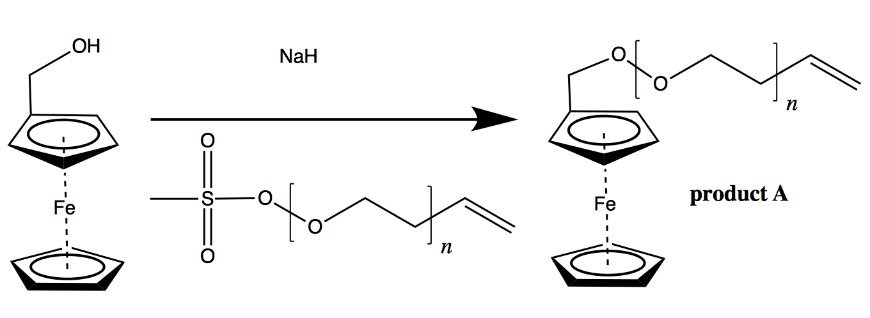

- Ferrocene-PEO Synthesis: Create monodisperse PEO chains via living anionic polymerization, then functionalize with ferrocene methanol to attach the cathode analog.

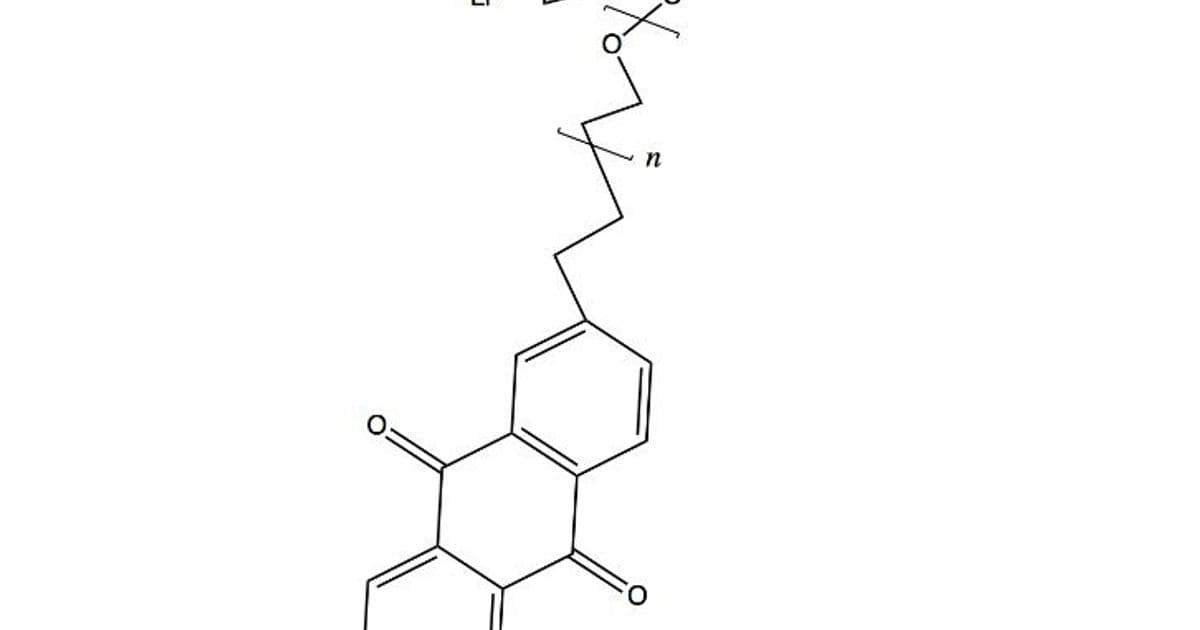

- Graphene-Anthraquinone Base: Covalently bond anthraquinone (anode analog) to a graphene substrate using aryldiazonium coupling, forming the negative electrode.

- Assembly: Couple the PEO-ferrocene chain to the anthraquinone-graphene base via Heck coupling, aiming for an oriented film. A top conductive contact completes the cell. {{IMAGE:5}}

Initial tests in a LiPF₆/DMC electrolyte could yield ~500 mV per cell. While modest, this validates the core principle—reactions confined to angstrom-scale distances enable rapid charge transfer. The real payoff, however, lies in scaling up.

Scaling Voltage and Energy: The Multi-Cell Dream

Single cells won’t suffice for practical use. McKay envisions oligomers with repeating units: conductive segments, reducers, ion conductors, and oxidizers, assembled in series like a molecular capacitor. This could achieve high voltages (e.g., 15–90V) in a nanometer-thin film. But critical barriers loom:

- Ion Shunting: Ions must move exclusively along the polymer chain, not between chains, to prevent voltage loss. Solutions might involve pendant groups or rigid backbones.

- Energy Density Trade-offs: Even optimistically, energy density (~250 kJ/L) lags behind lithium-ion (NMC: ~900 kJ/L) due to fixed 1:1 anode-cathode ratios. The focus here is power density—ideal for applications like burst-mode sensors or fast-charging microdevices.

- Polymerization Fidelity: High-voltage designs require near-perfect chain uniformity. Errors could cripple performance, as shown in McKay’s ‘Drake equation’ estimates:

# Simplified error impact model for a 30-cell chain

polymer_error_rate = 0.01 # 1% error

functional_cells = 30 * (1 - polymer_error_rate)**30

print(f"Usable cells: {functional_cells:.1f}") # Output: ~22.1 cells

Why This Matters—And Why It’s a Long Shot

For developers, this approach could enable embedded power sources in ultra-thin electronics, wearables, or IoT nodes where space and recharge speed trump capacity. Unlike conventional batteries, covalent bonding promises near-infinite cycles by preventing electrode degradation. Yet McKay concedes a ‘10% chance it works at all.’ Risks include poor conductivity, synthetic complexity, and electrolyte incompatibility. While academic labs could pioneer this—leveraging expertise in supramolecular chemistry—it’s too speculative for near-term commercialization. Still, as McKay notes, even failure here could yield insights for next-gen energy storage, echoing how explosive chemistry reshaped more than just warfare.

The potential is explosive, but the fuse is long. For now, it’s a tantalizing blueprint for those willing to explore chemistry’s frontiers.

Source: Adapted from Ian McKay’s article on Orca Sciences (Original Post).

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion