As AI-driven data centers threaten to consume 12% of US electricity by 2028, tech giants like Sam Altman and Jeff Bezos are betting on an audacious fix: launching these energy hogs into orbit. While space-based facilities promise unlimited solar power and freedom from Earth's environmental constraints, experts warn of staggering costs and radiation risks that could stall this sci-fi vision. Yet with startups already testing prototypes, the battle to balance AI's growth with planetary limits is r

As artificial intelligence propels an insatiable demand for computing power, the environmental toll of data centers has become impossible to ignore. These sprawling facilities—essential for training models like those from OpenAI—already guzzle vast amounts of electricity and water, with projections indicating AI data centers alone could spike global energy consumption by 165% by 2030. Alarmingly, over half their power still comes from fossil fuels, threatening to derail climate progress. Now, tech luminaries are floating a radical escape hatch: why not just send them to space?

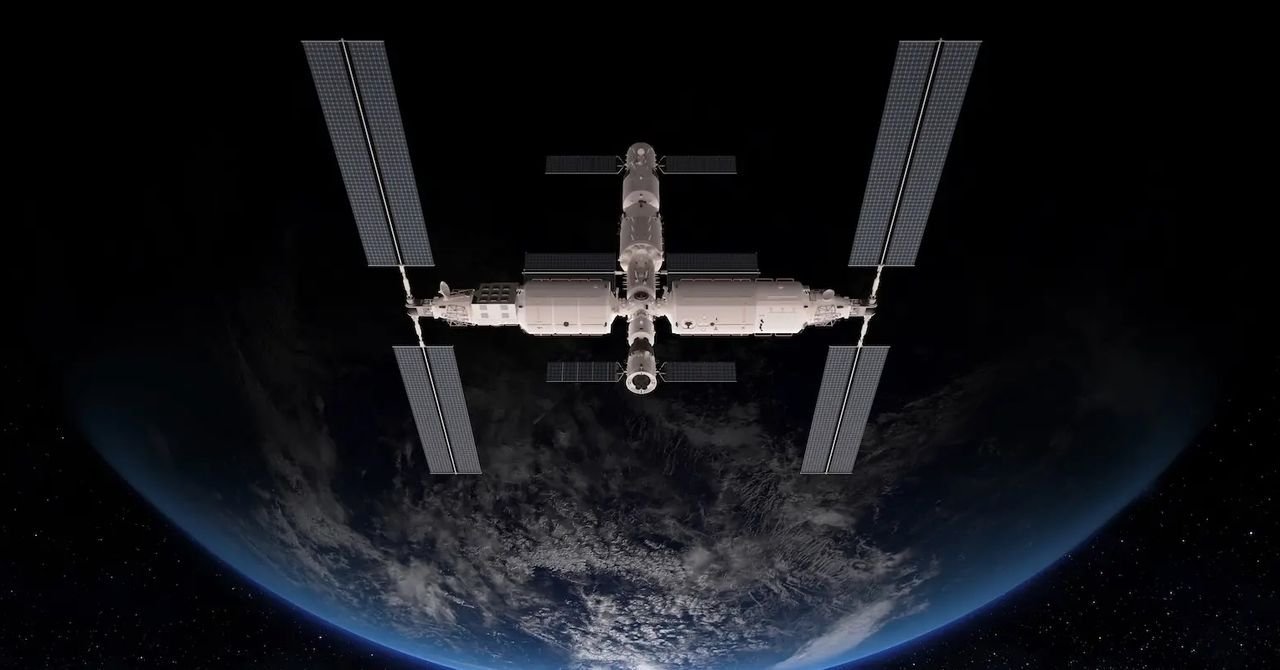

OpenAI CEO Sam Altman, in a candid discussion, acknowledged the dilemma: "I do guess a lot of the world gets covered in data centers over time." But with communities from Tucson to Virginia pushing back against local development over water and grid strains, he proposed an alternative: "Maybe we put them in space. I wish I had, like, more concrete answers for you, but like, we’re stumbling through this." Altman isn't alone; Jeff Bezos and Eric Schmidt are also exploring orbital data centers, with startups like Starcloud and Lonestar Data Systems securing millions to turn theory into reality.

The appeal is clear: space offers 24/7 solar energy, eliminating reliance on polluting power sources, and sidesteps terrestrial headaches like noise complaints or water shortages. Ali Hajimiri, an electrical engineering professor at Caltech, has even patented concepts for space-based computational systems. His research suggests lightweight solar arrays could eventually generate electricity at 10 cents per kilowatt-hour—cheaper than many Earth-bound alternatives. But Hajimiri cautions that the challenges are formidable:

"I never want to say something cannot be done, but there are challenges. Radiation bombardment would be constant, obsolescence would be a problem, and repairs would be confoundingly difficult. Definitely it would be doable in a few years—the question is how effective and cost-effective it would become."

Today, the economics remain prohibitive. Launching hardware costs roughly $1,500 per kilogram, and terrestrial data centers in hubs like Virginia’s "Data Center Valley" are far cheaper to build and maintain. Yet experimental efforts are underway: Lonestar recently landed a miniature data center on the moon (though it tipped over and failed), while Starcloud aims to deploy a fridge-sized satellite with Nvidia chips. Matthew Weinzierl, a Harvard economist studying space markets, notes that while orbital centers might serve niche roles—like processing space data or enhancing security—they can't yet compete on cost or performance: "To be a meaningful rival to terrestrial centers, they will need to compete on service quality like anything else."

Beyond engineering hurdles, the push reflects a deeper tension in tech's sustainability crisis. As Tucson councilmember Nikki Lee argued while rejecting a local data center, federal R&D should prioritize off-world solutions if AI is a "national priority." But Michelle Hanlon, a space law expert, points to another motivator: the regulatory void beyond Earth. "If you are a US company seeking to put data centers in space, then the sooner the better, before Congress is like, ‘Oh, we need to regulate that.’" This regulatory arbitrage could accelerate investment, even as it raises ethical questions about exporting environmental burdens.

For developers and engineers, the space data center concept isn’t just a curiosity—it’s a litmus test for the industry’s commitment to sustainable innovation. While orbital arrays might one day harness the sun’s boundless energy, the immediate future demands Earth-bound solutions: optimizing code efficiency, adopting renewables, and engaging with communities bearing the brunt of AI’s footprint. After all, as we gaze skyward for answers, the most critical server rooms might still be the ones we’re willing to build responsibly right here on the ground.

Source: Adapted from WIRED, part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion