A deep dive into the rising class of ORM Leak vulnerabilities shows how seemingly innocuous filtering features can expose passwords, tokens, and other secrets. From Beego in Harbor to Prisma authentication bypasses, the article explains the mechanics, real‑world exploits, and practical defenses.

ORM Leaks: When Filtering Becomes a Data Breach

In the past year, a new vulnerability class has emerged that sits at the intersection of ORMs and user‑controlled filtering. The class, dubbed ORM Leak, allows attackers to read sensitive columns—password hashes, API tokens, salts—by manipulating the field and operator that a web application forwards to its ORM. Unlike classic SQL injection, which often requires a flaw in query construction, ORM Leak relies on the application’s own filtering logic and the ORM’s dynamic query language.

Why it matters – Modern web stacks increasingly expose search and filter endpoints to end‑users. When the backend simply forwards a user‑supplied key to the ORM, the boundary between “safe” and “dangerous” fields collapses.

The Anatomy of an ORM Leak

| ORM | Typical dynamic filter syntax | Vulnerable sink |

|---|---|---|

| Django | filter(**{key: value}) |

filter() accepts arbitrary keys |

| Prisma | where: { [field]: value } |

where accepts dynamic keys |

| Beego | qs.Filter(key, value) |

Filter() accepts arbitrary keys |

| Entity Framework | Where(x => x.Prop == value) |

Where built from dynamic expressions |

The crux is that the ORM will translate a key like password__contains into a SQL LIKE clause. If the application never whitelists the key, an attacker can target any column.

Harbor’s Beego Exploit (CVE‑2025‑30086)

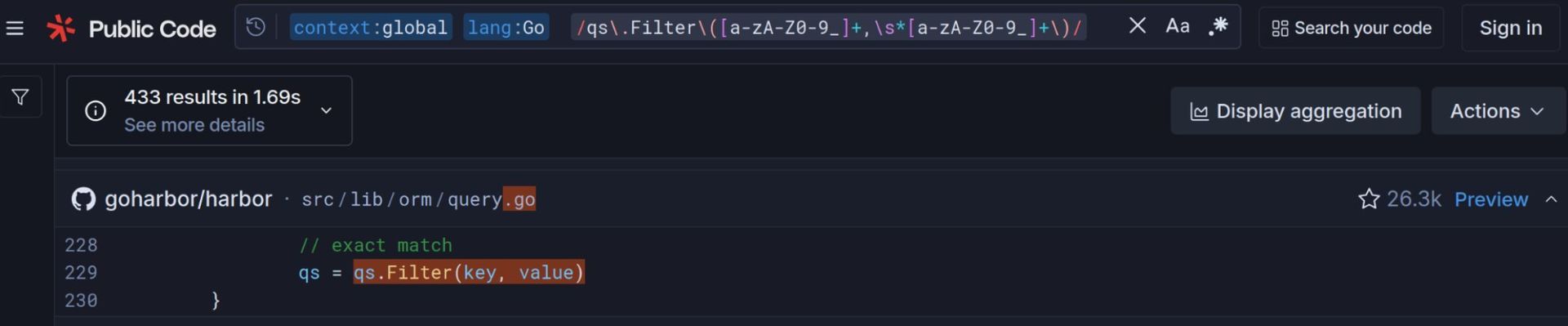

Harbor, the popular open‑source container registry, uses the Beego framework. A quick look at the setFilters function revealed a pattern that blindly forwarded user input to qs.Filter:

for key, value := range query.Keywords {

// ...

qs = qs.Filter(key, value) // <1>

}

<1> The sink that turns a user‑controlled

keyinto a query predicate.

The initial patch in v2.13.0 added a filterable flag, but it only inspected the first segment of the key. Because Beego’s Filter splits on __, an attacker could supply email__password__startswith, causing the ORM to interpret it as a filter on the password column.

Subsequent patches tightened the logic, but each time the mitigation was bypassed by leveraging Beego’s own parsing quirks. The final fix in v2.14.0 validated the entire expression against an allow‑list of operators.

Prisma Authentication Bypass

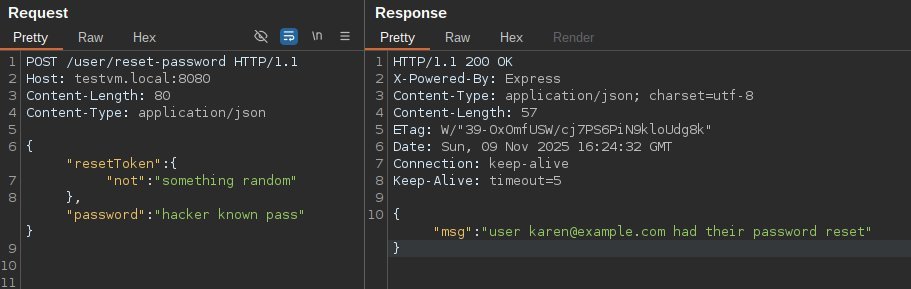

Prisma’s type‑safe query language is designed to be immune to injection. Yet, the framework itself is agnostic to how the query object is constructed. In a typical password‑reset endpoint, the code expected a plain string for resetToken:

const user = await prisma.user.findFirstOrThrow({

where: { resetToken: req.body.resetToken as string }

})

Because Express can parse URL‑encoded bodies with extended: true, an attacker can send resetToken[not]=E, which Express turns into { resetToken: { not: 'E' } }. Prisma interprets the not key as a filter operator, effectively negating the equality check and allowing the attacker to reset any user’s password.

This demonstrates that input type validation is as critical as ORM‑level safeguards.

Entity Framework and OData: The “Hidden” Leak Surface

Entity Framework (EF) is often considered safe because it builds LINQ expressions. However, when developers expose EF queries through OData, the framework automatically serialises navigation properties. If a User entity is linked to an Article, EF will include User in the OData model even if the developer didn’t explicitly add it. An attacker can then use $expand to pull in sensitive fields:

GET /Articles?$expand=CreatedBy&$filter=CreatedBy/Password eq '...'```

The standard mitigation—`IgnoreDataMember` on sensitive properties—relies on developers remembering to annotate every field. A single omission can expose a password hash.

## Common Themes Across ORMs

1. **Dynamic key handling** – Any ORM that accepts a key as a string is a potential sink.

2. **Operator parsing bugs** – Splitting on `__` or similar separators can be subverted if the parser doesn’t validate the entire expression.

3. **Framework‑level defaults** – OData, Beego, and even Prisma provide defaults that include sensitive fields unless explicitly excluded.

4. **Input type assumptions** – Treating JSON bodies as plain strings opens the door to NoSQL‑style injection.

## Defensive Strategies

| Layer | Action |

|-------|--------|

| **Input validation** | Whitelist acceptable keys and operators. Reject anything that references a disallowed column.

| **ORM configuration** | Use the ORM’s built‑in annotations (e.g., `filter:"false"`, `IgnoreDataMember`) and verify they are applied to every sensitive field.

| **Static analysis** | Deploy semgrep rules such as `django-orm-dynamic-lookup-variable-key` and `prisma-where-dynamic-key` to flag dynamic key usage.

| **Runtime monitoring** | Log and alert on unusual query patterns (e.g., `Password LIKE`) that appear in production.

| **Least‑privilege data exposure** | Avoid returning entire entities; instead, surface only the fields that the API consumer needs.

### Semgrep Detection

The author’s team released a set of semgrep rules that flag dynamic ORM lookups across Django, Prisma, Beego, and EF. These rules are not perfect but provide a good first line of defense. Running them on a codebase before a release can surface hidden vulnerabilities.

## Closing Thoughts

ORM Leak vulnerabilities illustrate a broader lesson: **security is not just about the underlying database engine but about how developers wire up filtering logic**. The trend toward richer, user‑driven search capabilities is undeniable, but it must be matched with rigorous field whitelisting, operator validation, and proactive tooling. As the article series concludes, the next wave of research will likely focus on automated detection and mitigation of these subtle leaks, ensuring that the convenience of dynamic ORMs does not come at the cost of data exposure.

Source: https://www.elttam.com/blog/leaking-more-than-you-joined-for/

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion