MIT physicists observed definitive evidence of quarks creating wakes in quark-gluon plasma, confirming the universe's primordial state flowed as a frictionless liquid.

In the first microseconds after the Big Bang, the universe existed as a trillion-degree-hot quark-gluon plasma (QGP) – a primordial soup of elementary particles flowing at near-light speeds. For decades, physicists debated whether this exotic state behaved as a cohesive liquid or a chaotic particle swarm. Now, an MIT-led team at CERN's Large Hadron Collider (LHC) has resolved this fundamental question by observing the first unambiguous evidence of quark wakes rippling through QGP. Their findings, published in Physics Letters B, demonstrate that this primordial substance flows with liquid-like properties, reshaping our understanding of the universe's earliest moments.

The Liquid Universe Hypothesis

Quark-gluon plasma is the hottest known liquid – estimated at several trillion degrees Celsius – and theoretically behaves as a near-perfect fluid with minimal viscosity. When heavy ions collide at relativistic speeds in particle accelerators, they create microscopic droplets of QGP that last mere quadrillionths of seconds. Researchers have long predicted that particles moving through this plasma should generate hydrodynamic wakes, similar to a boat trailing ripples on water. Yet previous attempts to detect these wakes failed because quark-antiquark pairs obscured each other's signatures.

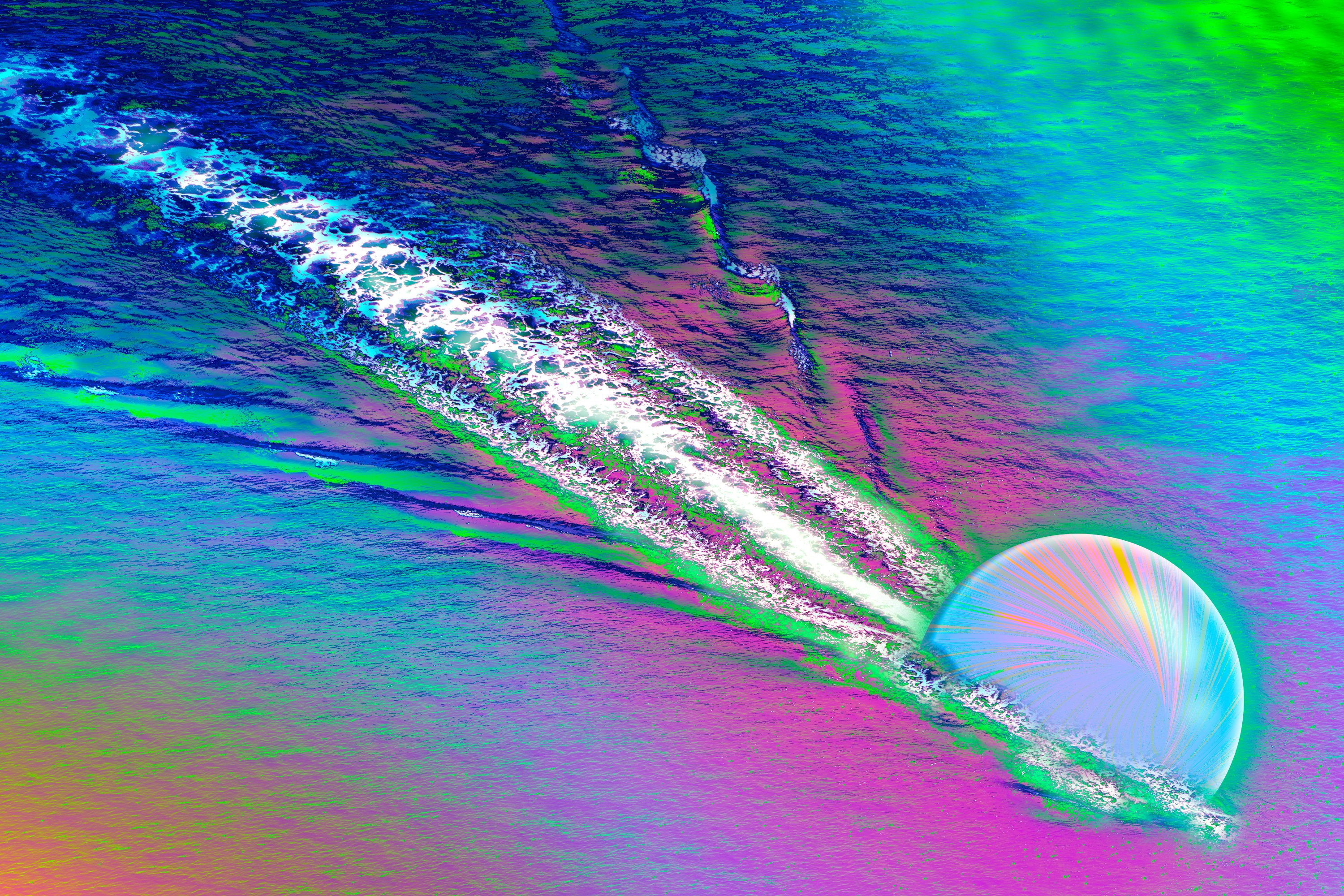

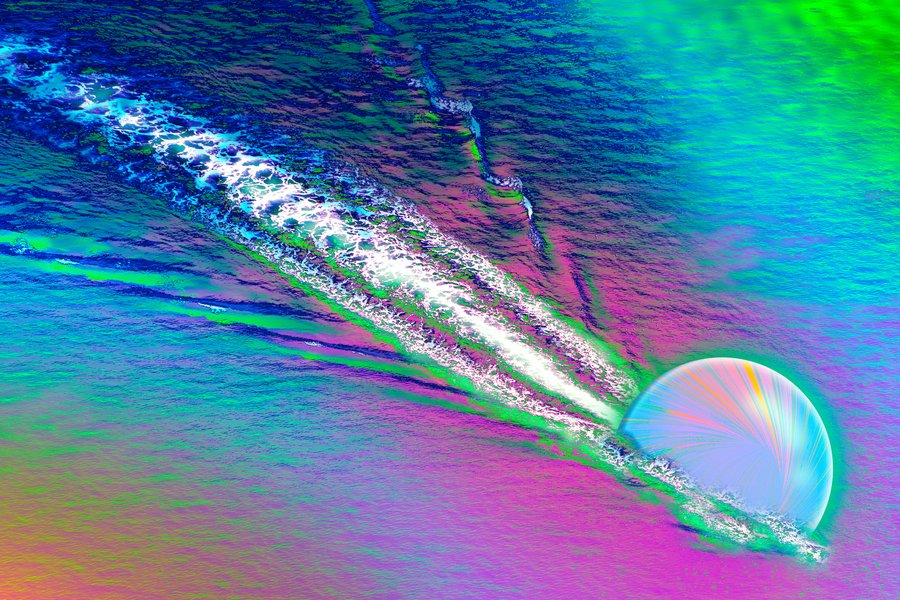

Caption: Graphic representation of quark-gluon plasma formation during high-energy collisions.

Caption: Graphic representation of quark-gluon plasma formation during high-energy collisions.

A Novel Detection Strategy

The breakthrough came from a clever experimental redesign. Instead of tracking quark pairs, the team exploited Z bosons – neutral particles that traverse QGP without interacting with it. By analyzing 13 billion lead-ion collisions in the LHC's Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS) detector, they identified ~2,000 events where a high-momentum quark was produced back-to-back with a Z boson.

"Z bosons act as perfect reference points," explains MIT professor Yen-Jie Lee. "They leave no wake, so any fluid disturbance we observe opposite their trajectory must originate solely from the quark."

Caption: Researchers inspecting the CMS detector at CERN, where quark-gluon plasma is recreated.

Caption: Researchers inspecting the CMS detector at CERN, where quark-gluon plasma is recreated.

Liquid Signatures Revealed

The team mapped energy distributions within the fleeting QGP droplets, consistently detecting asymmetric fluid patterns: concentrated energy near the quark's path that dissipated into swirls farther away. This matched hydrodynamic simulations based on MIT professor Krishna Rajagopal's hybrid model, confirming:

- Wake Formation: Quarks lose energy by displacing plasma, creating observable ripples

- Collective Flow: The plasma responds cohesively rather than through individual particle collisions

- Fluid Properties: Energy dissipation patterns reveal viscosity and density characteristics

Caption: Visualization of a quark (sphere) generating wake patterns in quark-gluon plasma (colorful medium).

Caption: Visualization of a quark (sphere) generating wake patterns in quark-gluon plasma (colorful medium).

Implications for Fundamental Physics

This discovery provides unprecedented tools for probing cosmic origins:

- Primordial Fluid Dynamics: Measuring wake propagation speeds and decay rates reveals QGP's transport coefficients

- Early Universe Snapshots: Wake patterns encode information about quark interactions during cosmic inflation

- Quantum Chromodynamics Validation: Confirms theoretical predictions about strong-force behavior under extreme conditions

The team now aims to quantify wake characteristics more precisely using upgraded LHC detectors. As Lee notes: "We've moved from debating QGP's liquid nature to measuring its exact properties – viscosity, sound speed, and how these influenced the universe's first structures."

Caption: Particle shower from proton-lead collision in the CMS detector.

Caption: Particle shower from proton-lead collision in the CMS detector.

Technical Limitations and Next Steps

While revolutionary, the technique faces challenges:

- Statistical limitations from rare Z-boson events

- Femtosecond-scale plasma lifetime requiring ultra-precise timing

- Background noise from concurrent particle interactions Future experiments will employ machine learning to isolate wake signatures from higher-energy collisions, potentially revealing how QGP properties vary across temperature ranges.

This research was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion