A groundbreaking proposal suggests a rectangular space telescope—dubbed DICER—could efficiently image Earth-like exoplanets by optimizing light collection along a single axis. This unconventional design promises to survey 30 potentially habitable worlds within 30 light-years in under three years, solving key engineering and cost barriers of traditional circular mirrors or interferometers.

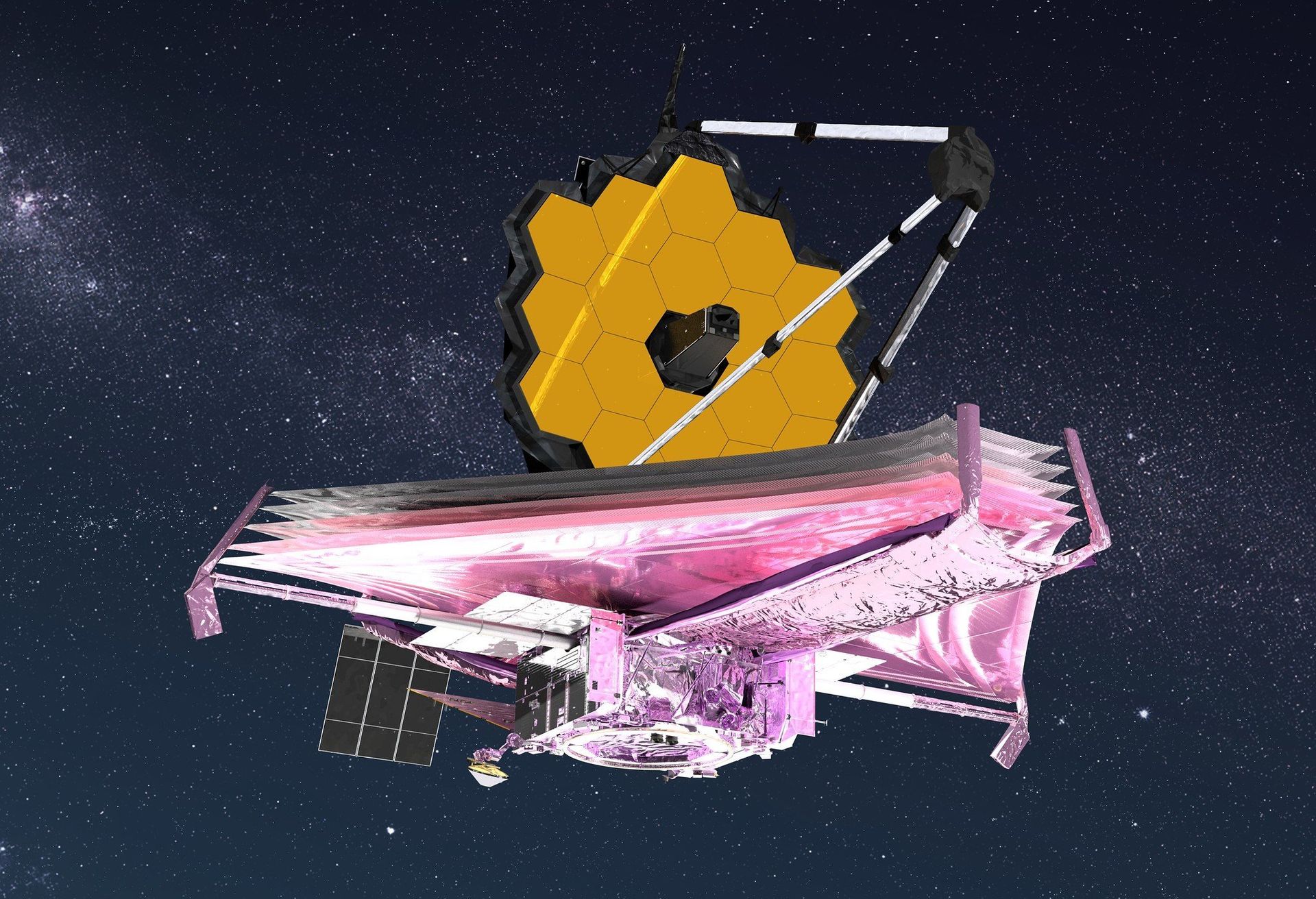

The search for Earth-like exoplanets demands telescopes capable of resolving faint, small worlds against the blinding glare of their host stars. While NASA's James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has advanced this quest, its 6.5-meter circular mirror remains too small to directly image Earth-sized planets in habitable zones around sun-like stars. A provocative new study proposes a radical solution: replace the circular mirror with a long, thin rectangle.

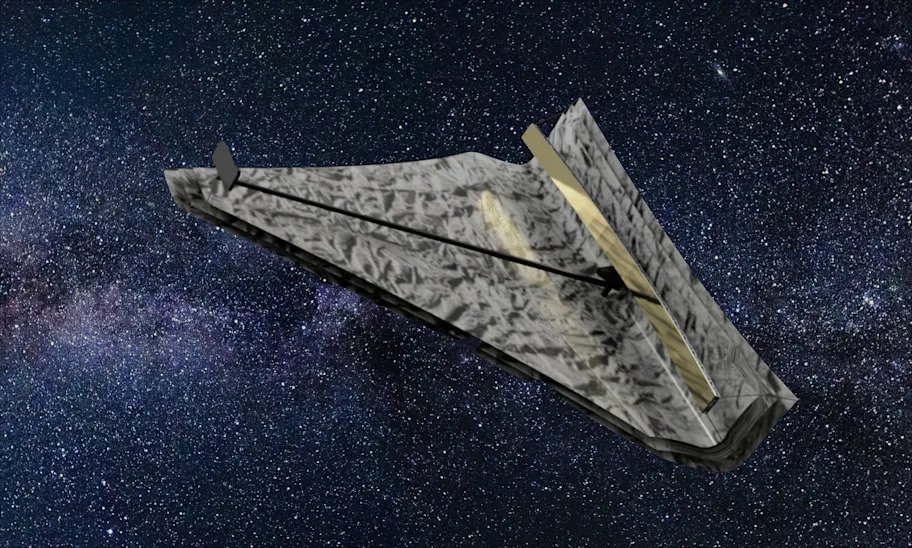

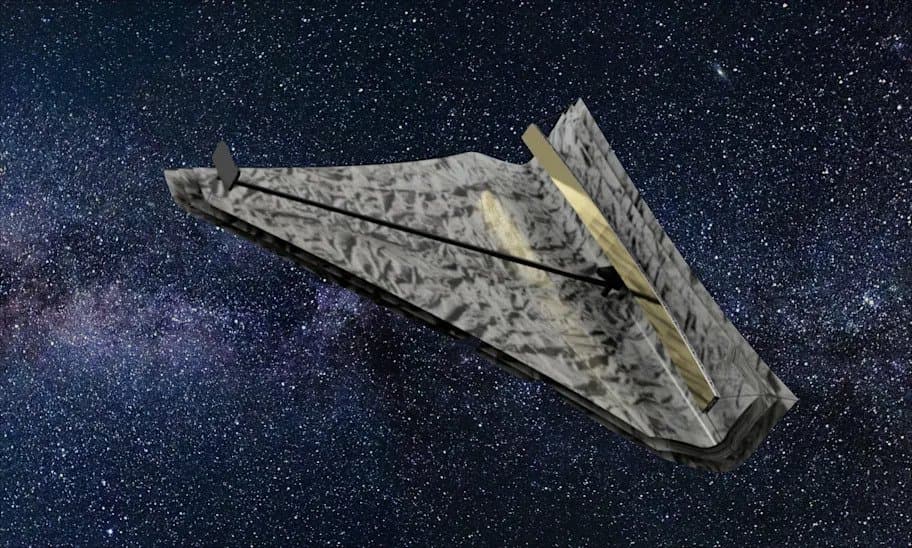

Concept design for the Diffractive Interfero Coronagraph Exoplanet Resolver (DICER). (Credit: Leaf Swordy/Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute)

Concept design for the Diffractive Interfero Coronagraph Exoplanet Resolver (DICER). (Credit: Leaf Swordy/Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute)

Led by Heidi Newberg at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, researchers argue that a 20-meter by 1-meter rectangular mirror could achieve the necessary resolution for detecting biosignatures like water vapor at 10-micron infrared wavelengths—where Earth-like planets are brightest relative to their stars. This exploits a critical optical principle: angular resolution depends on the maximum dimension of the telescope aperture perpendicular to the observation axis. By concentrating light-gathering area along one elongated direction, DICER sidesteps the need for a prohibitively large (and expensive) circular aperture.

"We show that it is possible to find nearby, Earth-like planets orbiting sun-like stars with a telescope that is about the same size as JWST... with a mirror that is a one by 20 meter rectangle," writes Newberg in Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences.

Why Rectangular Beats Circular or Interferometry

Current next-gen telescope concepts favor circular mirrors exceeding 8 meters or arrays of smaller telescopes acting as interferometers. Both face steep challenges:

- Gigantic Circular Mirrors: A 20m circular mirror (needed for 10-micron resolution at 30 light-years) would require unprecedented folding complexity for launch and immense cost.

- Interferometers: Precise nanometer-level alignment of multiple free-flying telescopes remains technically unfeasible and risky.

DICER’s rectangular approach offers compelling advantages:

- Simpler Engineering: Its linear structure is easier to fold and deploy than a massive segmented circle.

- Targeted Efficiency: By rotating the rectangle to align with a planet’s orbital plane, all collected photons contribute directly to resolving the planet. A circular mirror wastes photons collected perpendicular to this axis.

- Cost-Effectiveness: Despite its length, DICER’s total light-collecting area (20 m²) is smaller than JWST’s (25.4 m²), reducing material costs.

JWST’s circular design (shown here) can’t resolve Earth-like exoplanets—DICER’s rectangular shape could. (Credit: NASA GSFC/CIL/Adriana Manrique Gutierrez)

JWST’s circular design (shown here) can’t resolve Earth-like exoplanets—DICER’s rectangular shape could. (Credit: NASA GSFC/CIL/Adriana Manrique Gutierrez)

The Observational Payoff: 30 Worlds in 3 Years

Simulations indicate DICER could survey the 69 sun-like stars within 30 light-years, detecting water vapor signatures on planets in habitable zones. If Earth-analogs are common, it could identify ~30 candidate planets in under three years—a transformative leap. Crucially, it could also probe hundreds of cooler M-dwarf stars nearby.

This isn’t just theory; the rectangular design leverages existing infrared detector technology used by JWST’s MIRI instrument. The true innovation lies in rethinking aperture geometry to match the problem: resolving point sources separated by minute angles. As the astronomy community prioritizes exoplanet characterization for future flagship missions, DICER presents a paradigm shift—proving that sometimes, thinking outside the circle is the most rational path to finding other Earths.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion