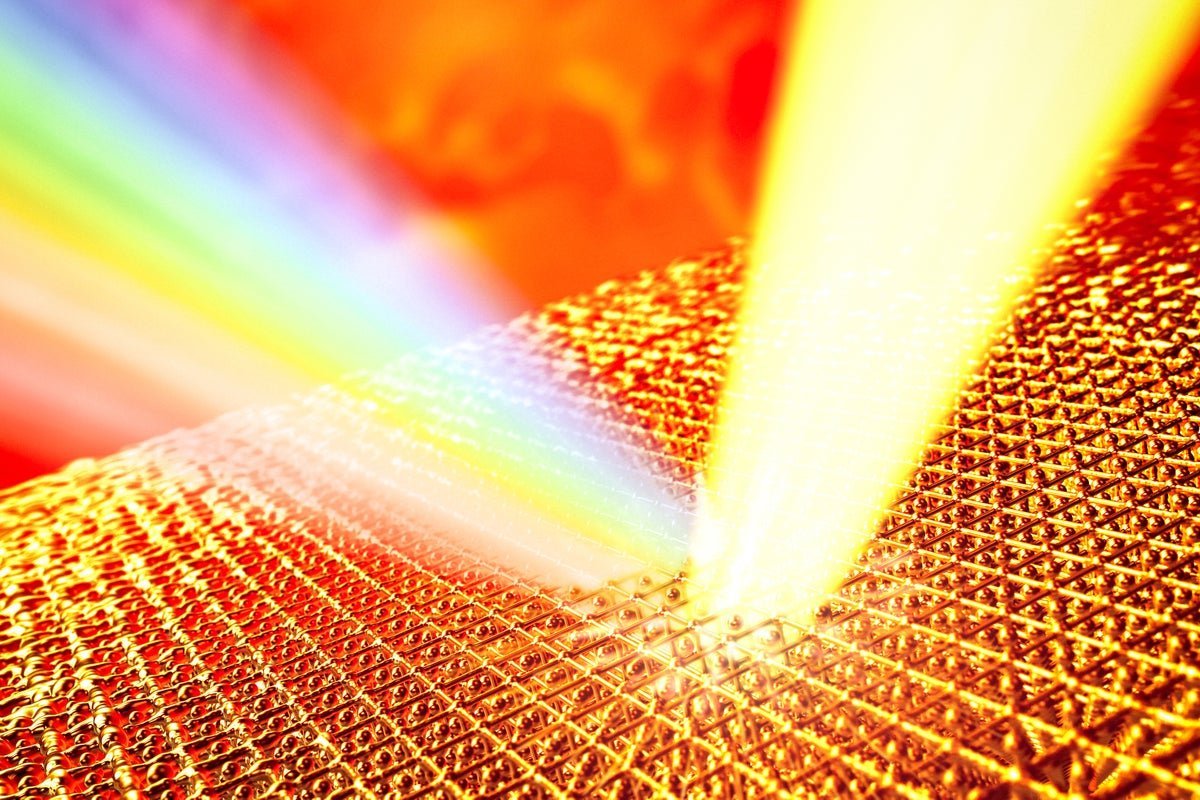

Physicists blasted nanometer-thick gold to 19,000 kelvins—14 times its melting point—using ultrafast lasers, overturning the long-standing 'entropy catastrophe' theory. This breakthrough reveals new states of warm dense matter and provides unprecedented temperature measurement techniques for fusion research and planetary science.

In a stunning violation of classical physics, researchers have superheated solid gold to 19,000 kelvins—33,740 degrees Fahrenheit and 14 times its conventional melting point—without liquefying the material. The experiment, conducted at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, demolishes a 40-year-old prediction called the 'entropy catastrophe,' which claimed solids couldn't exceed specific temperature thresholds without melting due to thermodynamic constraints.

The Entropy Catastrophe Overturned

For decades, physicists believed solids hit an inevitable 'entropy catastrophe' limit where atomic disorder (entropy) would force liquefaction. Beyond this point, theory suggested solid gold would paradoxically exhibit higher entropy than liquid gold—a thermodynamic impossibility. Yet when researchers fired a high-intensity laser at a nanometers-thick gold sample for just 45 femtoseconds (45 quadrillionths of a second), the metal remained solid at temperatures hotter than the sun's surface.

"This was extremely surprising. We were totally shocked when we saw how hot it actually got," said University of Nevada physicist Thomas White, co-author of the Nature study.

The key was ultrafast 'flash heating': the laser's femtosecond pulse heated atoms faster than they could rearrange or expand, preventing the entropy surge predicted by classical models.

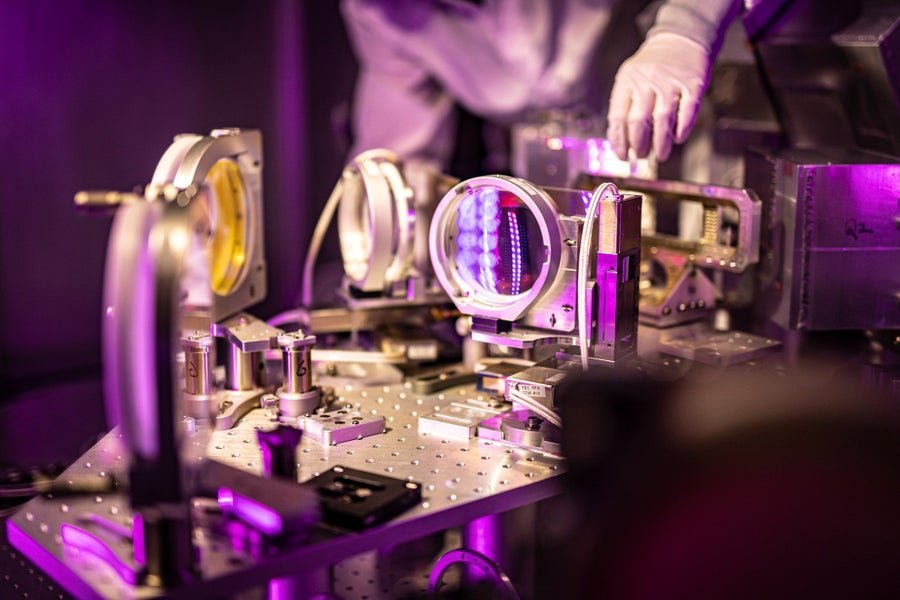

Project Scientist Chandra Curry at SLAC's Linac Coherent Light Source, where the breakthrough measurements occurred. (Credit: Jacqueline Ramseyer Orrell/SLAC)

Project Scientist Chandra Curry at SLAC's Linac Coherent Light Source, where the breakthrough measurements occurred. (Credit: Jacqueline Ramseyer Orrell/SLAC)

Probing Extreme Matter with X-Ray Vision

To measure this ephemeral superheated state, scientists used SLAC's 3-kilometer-long X-ray free-electron laser—the world's most powerful. It generated one trillion X-ray photons that scattered off gold atoms, enabling precise velocity measurements to calculate temperature.

"The biggest lasting contribution is that we now have a method to really accurately measure these temperatures," explained SLAC scientist Bob Nagler. This technique solves a longstanding challenge in studying 'warm dense matter'—the exotic state between solids and plasmas found in planetary cores and fusion reactors.

Implications: From Earth's Core to Fusion Futures

The team has already applied their method to laser-shocked iron foil simulating Earth's core conditions. "These questions are super important if you want to model the Earth," Nagler noted. More urgently, the technique can predict material behavior in nuclear fusion experiments like the National Ignition Facility, where precise melting points are critical for containing reactions.

While some researchers caution about extrapolating the findings—Chinese physicist Sheng-Nian Luo suggests ionization effects may complicate interpretations—the SLAC team maintains their results reveal "a genuinely new regime" of material science. As laboratories worldwide replicate this approach, we're not just rewriting physics textbooks; we're forging tools to probe the universe's most extreme environments and harness star-power on Earth.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion