A journey through the unexpected world of designing without graphical interfaces, from command-line video editing to code-driven document layout.

In the ever-evolving landscape of digital creativity, a quiet revolution is taking place—not with flashy new interfaces, but with a return to text. What if I told you that some of the most innovative design approaches today are happening not in graphical tools, but in the humble terminal? That's the journey I've found myself on, exploring a world where text in produces graphics out, challenging our assumptions about what design tools should be.

The spark that ignited this exploration wasn't some grand revelation, but rather a moment of frustration with modern design apps. I wanted to experiment with vertical videos, creating a specific aesthetic heavily filtered grayscale imagery with a faded black and white look, slightly pixelated, with a choppy frame count. Every app I tried fell short—CapCut felt unstable, others came with spammy upsells, and none could quite achieve the exact visual I envisioned.

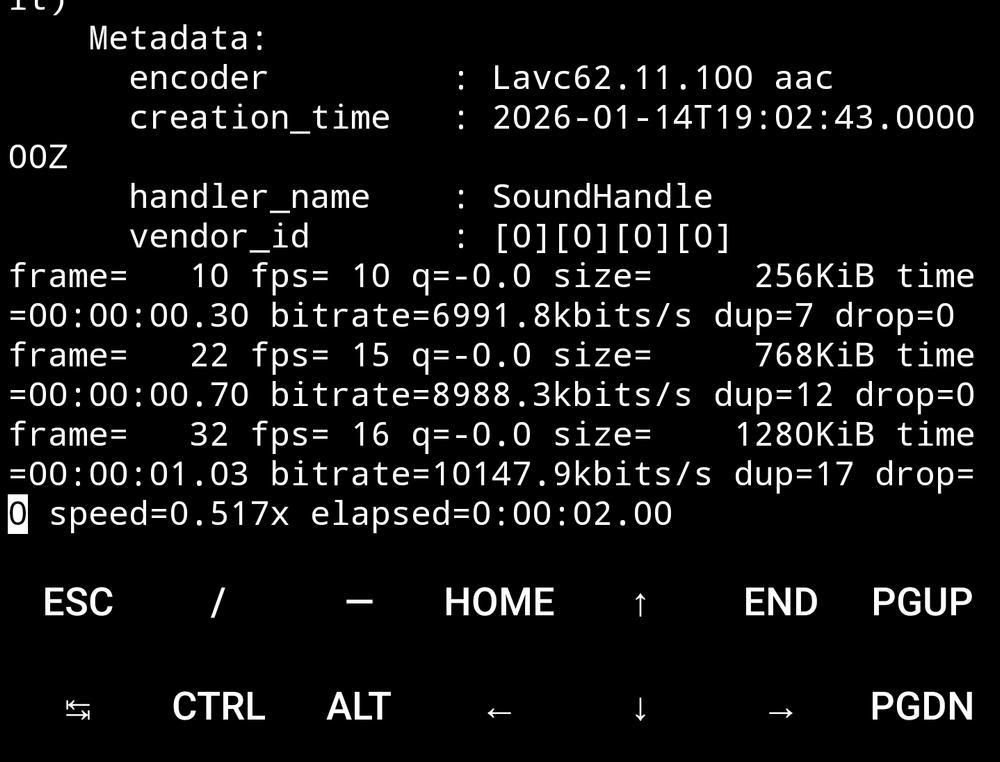

This limitation led me down an unexpected path: using ffmpeg in Termux, the Linux terminal emulator for Android, to filter videos to my exact specifications. The process was two-step: first, process the video in the terminal, then import to Canva for final touches including text and fonts. To my surprise, it worked beautifully. I had created precisely the visual effect I wanted, using a method that would have seemed impossibly technical just months earlier.

This experiment opened my eyes to a different way of thinking about design. What if we approached it not as a purely visual process, but as something more structured, more mathematical? As I later discovered, this isn't a new idea—graphic design has always had a hidden mathematical foundation. Ask any newspaper designer about pica rulers and column lengths, and they'll confirm that design is as much about precision and calculation as it is about creativity.

The real turning point came when I stumbled upon something that completely changed my perspective: a full YouTube video—complete with animation, graphics, and transitions—created entirely within a text editor. This led me to Vimjoyer, a creator who makes entire videos using Vim, the legendary modal text editor.

"This guy is nuts. I love what he's doing," I thought when I first saw his work. Using Vim for video editing is like using scissors to cut a watermelon—technically possible, but seemingly impractical. Yet Vimjoyer makes it work, primarily through Motion Canvas, a tool that allows for code-first animation design with a graphical interface secondary.

This approach represents a fundamental shift in how we think about creative tools. Rather than the traditional graphics-in, graphics-out model, we're seeing text-in, graphics-out systems that separate the creative process from its visual representation. This separation of concerns—between content structure and visual presentation—echoes the principles that gave us HTML, CSS, and JavaScript for web design.

My curiosity led me to explore similar tools that work within command-line environments. While Motion Canvas required a browser, I discovered Remotion, which operates entirely through the command line. Though it required Playwright (a headless browser tool), I found workarounds that allowed me to implement these text-based design workflows directly on my phone.

The implications of this approach extend far beyond video editing. I've been experimenting with creating social graphics from Markdown files, essentially using HTML and CSS to generate visual content programmatically. This method allows me to write content in a simple markup language and have it automatically formatted according to predefined style guidelines.

Every tech journalist in 1995 overestimated, then underestimated, the Zip drive. This historical pattern of overhyping then dismissing new technologies reminds us that innovation often follows an unpredictable path. The text-based design movement is still in its early stages, but it's showing promise as a complementary approach to traditional design tools.

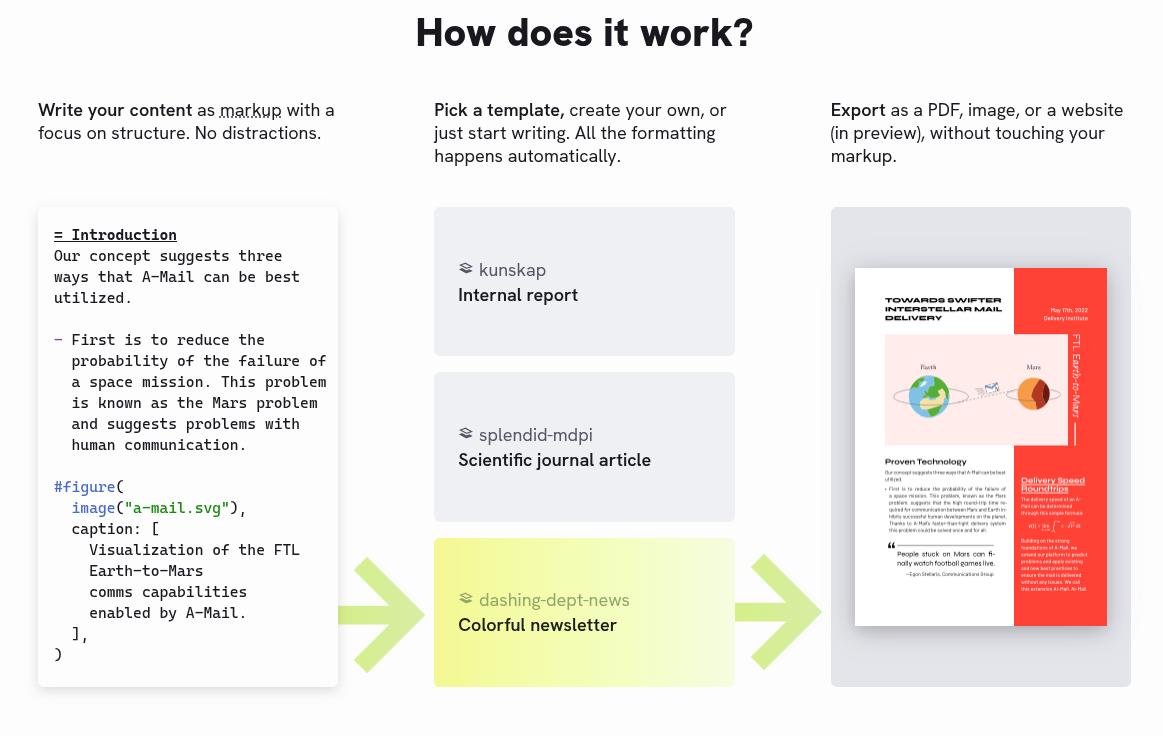

One particularly exciting development I've discovered is Typst, a markup-based document typesetting system positioned as a modern alternative to LaTeX. While LaTeX users have been designing with code for decades, Typst offers a more accessible entry point while maintaining powerful layout capabilities.

Typst excels at technical document layout, particularly for content with mathematical equations, but its potential extends far beyond academic papers. I've experimented with creating complex documents like zines and even wall calendars—projects that would be cumbersome in traditional design software due to their highly templated nature.

Imagine creating a wall calendar where each month's layout is defined by a simple script, allowing for consistent styling while easily accommodating different content lengths. This is where text-based design truly shines: when you need precision, repeatability, and the ability to manage complex layouts without getting lost in visual interfaces.

The beauty of this approach lies in its ability to separate concerns. For example, you might use a traditional tool like Affinity or Inkscape to create the basic visual elements—an SVG with shapes or backgrounds—but then import those assets into Typst for the actual layout and composition. This hybrid approach leverages the strengths of different tools while maintaining a clear separation between visual design and structural layout.

What makes text-based design particularly compelling is how it aligns with how our brains actually work. Graphic designers are often stereotyped as purely right-brained creatives, but the reality is more nuanced. Effective design requires both creative vision and mathematical precision—a balance between artistic intuition and structural thinking.

This realization was crystallized for me through Markdown, particularly early editors like Mou that presented a split view showing both the markup and the rendered output in real time. Though Mou's story ended unhappily with its developer disappearing after a crowdfunding campaign, its influence persists through spiritual successors like MacDown 3000 and continues to shape how we think about content creation.

The principle I discovered through these experiments applies broadly: frameworks enable creativity. When you establish clear structures and constraints, you free yourself to focus on what truly matters—the content and its presentation. This philosophy guided me when I started ShortFormBlog in 2009, with the idea that individual posts could have unique designs while maintaining coherence through a well-defined framework.

Looking ahead, the potential for text-based design continues to expand. Tools like Typst could evolve to include features like blend modes, clipping paths, and advanced typography, potentially becoming comprehensive publishing tools that work alongside rather than replacing traditional design software.

We already have a robust text-based framework for web design in HTML, CSS, and JavaScript. With further development, tools like Typst could provide a similar foundation for print and digital publishing, offering precision and repeatability while maintaining design flexibility.

The journey into text-based design isn't about rejecting visual tools—it's about expanding our creative toolkit. By understanding both approaches, we can choose the right tool for each task, whether that means working directly in a graphical interface or defining designs through code.

As I continue down this path, I'm reminded that innovation often comes from unexpected places. The ability to create compelling visuals through text isn't just a technical curiosity—it represents a fundamental shift in how we think about the relationship between content and form, between structure and presentation.

In an increasingly visual digital world, returning to text might just be the most forward-thinking approach to design we can take.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion