Apple's Lisa computer pioneered the graphical user interface and powerful hardware in 1983, yet met a shocking end: 2,700 units crushed in a landfill. Its tale reveals a perfect storm of exorbitant pricing, internal competition from the Macintosh, and brutal business realities that doomed a technical marvel. This is the inside story of ambition, failure, and the landfill that became a tech tomb.

In the annals of tech history, few images are as jarring as bulldozers burying thousands of pristine computers. In 1989, that's precisely what Apple did to approximately 2,700 of its Lisa machines in a Utah landfill. This wasn't just disposal; it was the ignominious end for a computer that once promised to revolutionize personal computing.

The Lisa's Lofty Promise

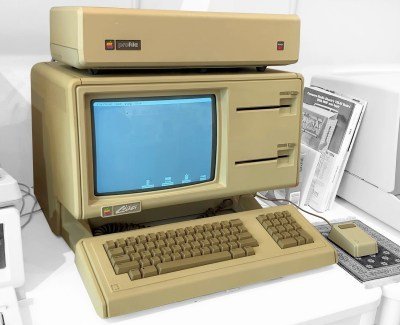

Launched in 1983, the Apple Lisa was a breathtaking leap forward. Officially standing for "Local Integrated Software Architecture" (though widely believed to honor Steve Jobs' daughter), it represented Apple's bold vision for the future. It abandoned the 6502 CPU for the powerful Motorola 68000 running at 5 MHz, boasted a groundbreaking graphical user interface (Lisa OS) with icons and a mouse, a high-resolution 720 x 364 monochrome display, twin 5.25" floppy drives, and a generous 1MB of RAM.

"The Lisa was groundbreaking in ways that wouldn’t be fully appreciated until years later."

It was, by any measure, a technical marvel far beyond the text-based IBM PCs or even Apple's own Apple II. But this power came at a staggering cost: $9,995 at launch – over $30,000 in today's dollars.

It was, by any measure, a technical marvel far beyond the text-based IBM PCs or even Apple's own Apple II. But this power came at a staggering cost: $9,995 at launch – over $30,000 in today's dollars.

The Seeds of Failure: Price, Performance, and Internal Rivalry

The Lisa's astronomical price immediately placed it out of reach for most consumers and businesses. While revolutionary, its GUI was also notoriously sluggish on the hardware of the time, earning it a reputation for being underpowered despite its specs. Compounding these issues was a seismic shift happening within Apple itself.

Steve Jobs, initially involved with Lisa, was famously ousted from the project in 1981. He shifted his formidable energy and ambition to the nascent Macintosh project. Originally conceived as a low-cost text-based machine, Jobs redirected it to become a GUI-based computer like the Lisa, but crucially, designed to be affordable. Rumors of this cheaper alternative swirled even as the Lisa launched.

The Macintosh Cometh: A Death Knell

When the Macintosh debuted in January 1984, propelled by the iconic "1984" Super Bowl ad, it delivered a Lisa-like GUI experience at a fraction of the cost: $2,495. While less powerful (only 128K RAM, a smaller screen, and a single 3.5" floppy drive), the price difference was insurmountable. The market voted decisively: Apple sold 70,000 Macs in its first few months. It took the Lisa two years to sell just 50,000 units.

Apple scrambled, releasing the Lisa 2 and rebadging it as the Macintosh XL with significant price cuts (down to $3,995 by 1985). However, the damage was done. By 1986, the Lisa line was discontinued.

The Landfill: A Calculated Corporate Decision

Thousands of unsold Lisas remained. A company called Sun Remarketing bought about 5,000, upgrading and reselling them. But in 1989, Apple made a final, brutal decision regarding the remaining 2,700 units: landfill burial in Logan, Utah.

The move made headlines, shocking in an era where computers were still expensive novelties. Apple's rationale was purely financial. As spokesperson Carleen Lavasseur stated at the time:

"Right now, our fiscal year end is fast approaching and rather than carrying that product on the books, this is a better business decision."

Destroying the inventory allowed Apple to claim a significant tax write-off, estimated at recovering up to $34 for every $100 of the machines' depreciated value. Guards reportedly ensured the Lisas were crushed beyond recovery.

Legacy: The High Cost of Pioneering

The Lisa's story is a stark lesson in the intersection of innovation, market forces, and corporate strategy. Its technological contributions – the GUI, the mouse, powerful multitasking – were undeniable and paved the way for the Macintosh and modern computing. Yet, its failure was equally multifaceted: prohibitive cost, performance hiccups, and crucially, being cannibalized by a cheaper, more focused sibling product championed by its own exiled creator.

The landfill burial wasn't just about hiding failure; it was a cold, calculated act of accounting, turning physical machines into a tax deduction. While the Lisa itself was buried, its spirit – the drive for graphical, user-friendly computing – lived on, proving that even the most spectacular flops can lay the groundwork for revolutions, just not always for those who built them first. The bulldozers in Utah didn't just cover computers; they buried a specific, costly vision of the future, making way for the one that ultimately won.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion