A developer has created the fastest general-purpose SGP4 satellite propagation library, achieving 11-13 million propagations per second in native Zig and 7 million per second through Python bindings, all without a GPU. This article explores the technical journey, from leveraging Zig's comptime and SIMD features to solving the unique challenges of vectorizing a complex algorithm, revealing how thoughtful language design can unlock performance in unexpected domains.

The quest for computational speed often leads developers to GPUs, specialized hardware, or complex distributed systems. Yet, sometimes the most profound gains come from a deeper understanding of a single CPU's capabilities and the language that orchestrates them. This is the story of astroz, a new SGP4 satellite propagation library that achieves 11-13 million propagations per second in native Zig and 7 million per second through Python bindings, all on a standard CPU. It's a case study in how modern language features—specifically Zig's comptime and first-class SIMD support—can be harnessed to breathe new life into decades-old algorithms.

SGP4, the Standardized General Perturbation 4 algorithm, is the workhorse for predicting satellite positions from Two-Line Element (TLE) data. It's been the standard since the 1980s, and most implementations are straightforward ports of the original reference code. They work, but "fine" becomes a bottleneck when workloads scale. Generating a month of ephemeris data at one-second intervals requires 2.6 million propagations per satellite. Pass prediction over a ground station network or conjunction screening for trajectory analysis demands similar density. At typical speeds of 2-3 million propagations per second, these tasks take seconds per satellite—a delay that compounds quickly in iterative analysis or interactive tools.

The author's journey began not with SIMD, but with a scalar implementation that already outperformed expectations. The Rust sgp4 crate, a respected open-source implementation, was matched or slightly beaten by a straightforward Zig port. This initial speed wasn't from clever micro-optimizations but from two design choices that aligned perfectly with modern CPU architecture and Zig's compilation model.

First, the hot paths were written branchlessly where possible. The SGP4 algorithm is riddled with conditionals: deep space versus near-earth models, different perturbation calculations, and convergence checks in the Kepler solver. Writing these as branchless expressions initially made the code easier to reason about. It was a happy accident that this also gave CPUs predictable instruction streams, minimizing costly branch mispredictions.

Second, Zig's comptime feature was used aggressively. comptime allows arbitrary code execution at compile time. In SGP4, many setup calculations—gravity constants, polynomial coefficients, derived parameters—can be computed once and baked directly into the binary. This eliminates runtime initialization and repeated calculations. Zig's compiler is smart enough to treat const variables as comptime by default, making this optimization nearly effortless. The result was a scalar implementation running at ~5.2 million propagations per second, already edging out Rust's ~5.0 million.

This success revealed a deeper opportunity. SGP4's core design is inherently parallel: each satellite and each time point is independent. This independence is tailor-made for Single Instruction, Multiple Data (SIMD) processing. Historically, SIMD implementation has been a nightmare—requiring platform-specific intrinsics, conditional compilation, and complex code that's difficult to maintain. The author's discovery was that Zig treats SIMD as a first-class citizen, abstracting away the platform-specific complexity.

The foundation is a simple type declaration: const Vec4 = @Vector(4, f64);. This creates a 4-wide vector of 64-bit floats. No intrinsics, no platform detection. The LLVM backend handles targeting the right instruction set. Built-in operations are equally straightforward. Broadcasting a scalar to all lanes uses @splat. Trigonometric functions like @sin and @cos map directly to LLVM intrinsics, which use platform-optimal implementations like libmvec on Linux x86_64.

The real mental shift was learning to think in lanes. In scalar code, an if statement directs the CPU down one path. In SIMD, all lanes execute together. If lane 0 needs the "true" branch and lane 2 needs the "false" branch, you must compute both outcomes and select per lane. This initially felt wasteful, but modern CPUs are so fast at arithmetic that computing both and selecting is often faster than dealing with branch misprediction. For SGP4, most satellites follow the same path anyway, minimizing truly "wasted" work.

The trickier challenge was convergence loops in the Kepler solver. In scalar code, you iterate until a single result converges. In SIMD, different lanes converge at different rates. The solution is to track convergence per lane with a mask and use @reduce to check if all lanes are complete. This pattern—compute everything, mask the results, reduce to check completion—became the foundation for the vectorized implementation.

With these patterns established, the author built three distinct propagation strategies for different workloads:

Time-Batched (

propagateV4): Processes 4 time points for one satellite simultaneously. This is ideal for generating ephemeris data, pass prediction, or trajectory analysis. It's highly cache-friendly, as the satellite's orbital elements remain in registers while computing four outputs.Satellite-Batched (

propagateSatellitesV4): Processes 4 different satellites at the same time point. This is optimized for collision screening snapshots or catalog-wide visibility checks. It requires a different data layout—a "struct of arrays" where each field is aVec4holding values for four satellites. Pre-splatting constants at initialization eliminates repeated@splatcalls in the hot path.Constellation Mode (

propagateConstellationV4): Combines both, propagating many satellites across many time points. This mode uses cache-conscious tiling. Instead of processing all time points for one satellite (which thrashes the cache), it processes a tile of time points (e.g., 64) for all satellites, then moves to the next tile. This keeps time-related data hot in the L1/L2 cache, yielding a 15-20% speedup over naive loops for large catalogs.

A particularly interesting problem was the atan2 function, required by the Kepler solver. LLVM doesn't provide a vectorized builtin for it. Calling the scalar function would break the SIMD implementation. The solution was a polynomial approximation, accurate to ~1e-7 radians. This translates to a position error of about 10mm at LEO distances, well within SGP4's inherent accuracy limits, which are measured in kilometers over multi-day propagations.

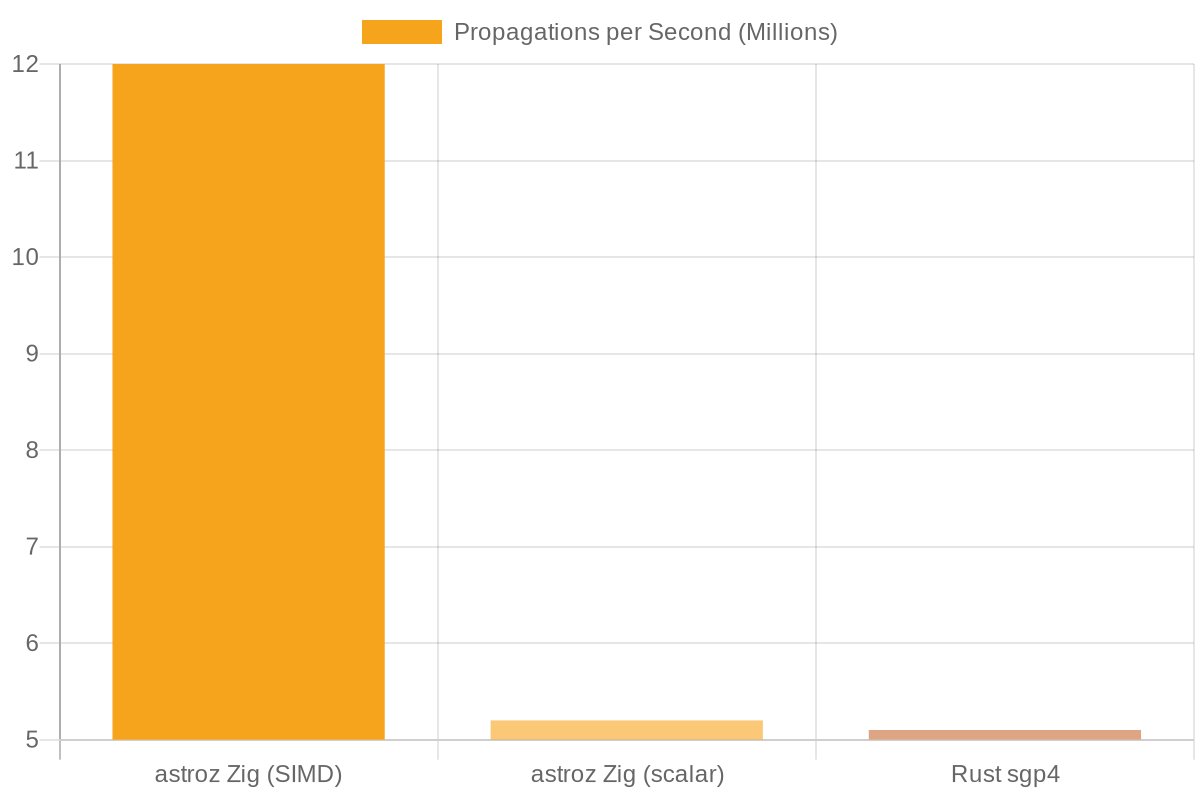

The benchmark results are compelling. In a native comparison, astroz (Zig) consistently edges out the Rust sgp4 crate, with speedups ranging from 1.03x to 1.16x. The real leap comes from SIMD: throughput jumps to 11-13 million propagations per second, more than double the scalar implementations.

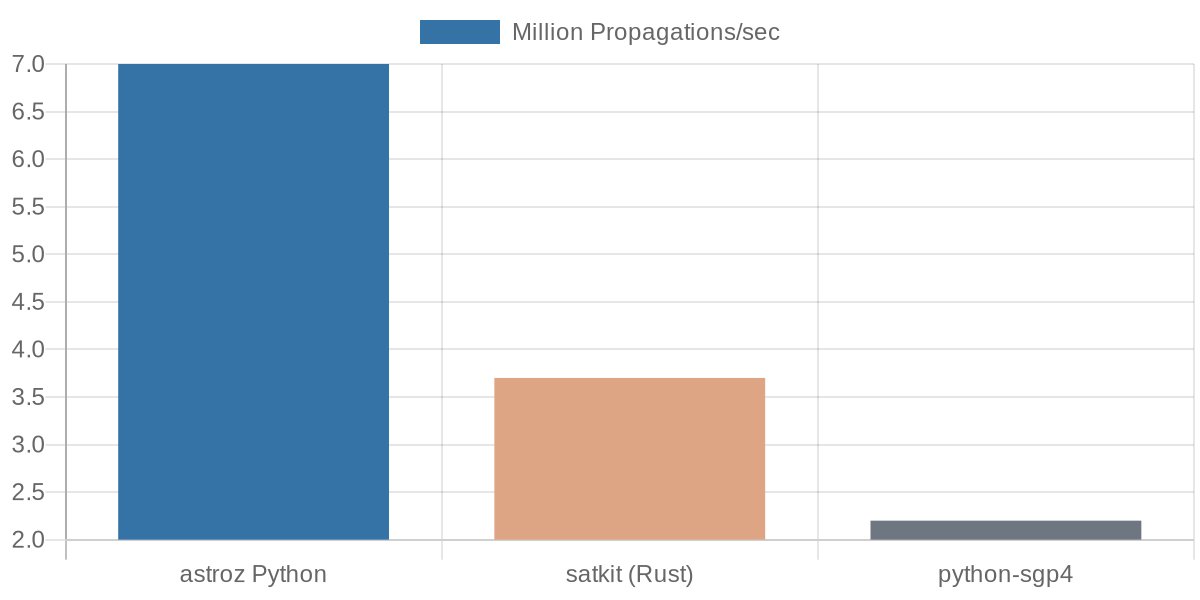

For Python users, astroz bindings achieve ~7 million propagations per second, compared to ~2.2 million for the popular python-sgp4 library—a nearly 3x speedup. This makes high-performance satellite propagation accessible from Python with a simple pip install astroz.

It's important to note the context. The author compares astroz to heyoka.py, a general ODE integrator with an SGP4 module. heyoka.py wins for batch-processing many satellites simultaneously (16M/s vs 7.5M/s), but it requires LLVM for JIT compilation and a complex C++ dependency stack. For time-batched propagation (many time points for one satellite), astroz is 2x faster (8.5M/s vs 3.8M/s). The choice depends on the workload: heyoka.py for massive satellite batches, astroz for dense time series of individual satellites.

The performance enables new kinds of interactive tools. The author built a live demo propagating the entire active satellite catalog (~13,000 satellites) across 1,440 time points (a full day at minute resolution). That's ~19 million propagations completing in about 2.7 seconds. Adding coordinate conversion brings the total to ~3.3 seconds. This transforms what was a batch job into an interactive experience.

The work is ongoing. Next steps include adding SDP4 for deep-space objects and multithreading to scale across CPU cores. The SIMD work here was single-threaded; there's another multiplier waiting.

This project is more than a performance hack. It's a demonstration of how language design influences what's possible. Zig's comptime and SIMD abstractions lowered the barrier to entry for high-performance computing, allowing a developer to focus on the algorithm rather than the platform. It shows that sometimes, the path to computational speed isn't through more hardware, but through a deeper partnership with the hardware we already have.

The code is open source on GitHub. You can install it via pip install astroz or add it to a Zig project with zig fetch --save git+https://github.com/ATTron/astroz/#HEAD. The live demo showcases the performance in action, and the examples provide integration guidance. For the original SGP4 specification, see SpaceTrack Report No. 3.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion