When a student asked about the fundamental difference between files and directories in Unix-like systems, it revealed a deeper exploration of filesystem architecture. This technical deep dive examines how inodes store metadata, why directories are special types of files, and what happens when you exhaust inode space—complete with practical demonstrations on ext4.

A deceptively simple question from a student—"What's the difference between files and directories in Unix, and what role do inodes play?"—unlocks a fascinating journey into the core architecture of Unix-like filesystems. While the classic mental model portrays an inverted tree structure with files as leaves and directories as branches, the reality involves intricate metadata management that shapes everything from file retrieval to storage limits.

The Metadata Backbone: Inodes Demystified

At the heart of Unix filesystems lies the inode (index node), a data structure storing all metadata about a file—except its name. This includes:

- Permissions and ownership

- Timestamps (creation, modification, access)

- Size and disk block locations

- Link count

As the Linux inode(7) manual emphasizes, inodes act as the "source of truth" for file attributes, separated from actual data blocks. Crucially, directories are also files—just with a special flag in their inode marking them as containers of directory entries (dirents).

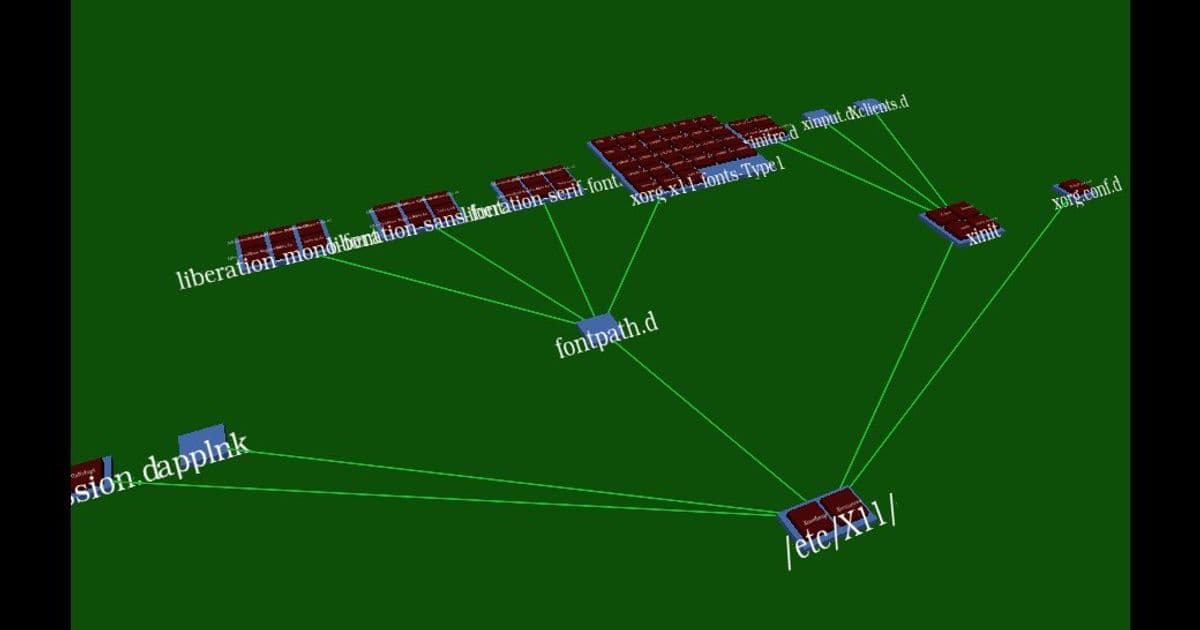

An artistic (and inaccurate!) representation of an inode—real ones are less whimsical but far more powerful.

An artistic (and inaccurate!) representation of an inode—real ones are less whimsical but far more powerful.

Directories Under the Microscope

A directory’s dirent table maps human-readable filenames to inode numbers. When you run ls -la, you’re effectively reading this table. To demonstrate:

# Create a 128MB test filesystem

dd if=/dev/zero of=test.img bs=1M count=128

losetup -f test.img

mkfs.ext4 /dev/loop0

mount /dev/loop0 /mnt

After creating thousands of empty files:

stat . # Shows directory block count skyrocketing

df -ih . # Reveals 100% inode usage (32K allocated)

The surprise? Empty files consume no data blocks but exhaust inodes—a quirk of fixed inode allocation in traditional filesystems like ext4. This mirrors real-world headaches, like compiling Gentoo on space-constrained systems where inode exhaustion halts operations despite free space.

Modern Filesystems: Beyond Static Inodes

While ext4 and UFS pre-allocate inodes, scalable systems like ZFS and Btrfs dynamically manage metadata. They maintain Unix API compatibility—allowing Solaris/FreeBSD to boot from UFS or ZFS interchangeably—while revolutionizing underlying mechanics. For example, ZFS replaces inodes with "dnodes" that scale with storage pools.

Why This Still Matters

Understanding inodes isn’t academic trivia:

- Performance: File operations depend on inode/dirent efficiency.

- Troubleshooting: "No space left on device" errors often mean exhausted inodes, not storage.

- Security: Directory permissions hinge on their file-like attributes.

As filesystems evolve, the inode’s legacy persists—a testament to Unix’s enduring design. Next time you cd into a directory, remember: you’re traversing a specially crafted file, guided by metadata older than Linux itself.

Source: Jack23247's Blog

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion