Discover why physically accurate hanging wires—catenaries—are notoriously difficult to implement in games despite their prevalence in environments, from Portal to Half-Life. We break down the complex mathematics behind these curves and why numerical solutions trump closed-form equations for real-time rendering.

The Uncanny Valley of Virtual Chains

Walk through any decaying sci-fi facility in modern games like Half-Life: Alyx or Portal, and you’ll spot them instantly: drooping cables, suspended wires, and chains that drape between anchors. These shapes aren’t arbitrary—they follow a precise mathematical curve called a catenary, derived from the Latin catenaria (chain). Yet, as Alan Zucconi notes, many games get them wrong, plunging players into an "uncanny valley of hanging objects."

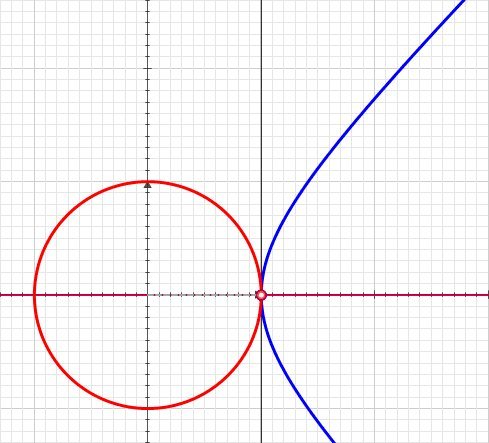

Why? While real chains naturally sag into this form, its mathematical representation is deceptively complex. The ideal catenary is defined by the hyperbolic cosine function:

y = a \cdot \cosh\left(\frac{x}{a}\right)

Here, a controls the curve’s "sag," but this equation assumes symmetry and uniform density. Games rarely have that luxury. Anchors sit at uneven heights (y₁ ≠ y₂), and artists need control over chain length (L) and sag magnitude. This transforms a neat formula into a transcendental nightmare:

L = a \cdot \sinh\left(\frac{x_2 - x_1}{2a}\right) \cdot \sqrt{1 + \left(\frac{y_2 - y_1}{x_2 - x_1}\right)^2}

Hyperbolic functions underpin catenaries, emerging from force-balance differential equations (Credit: Alan Zucconi)

Hyperbolic functions underpin catenaries, emerging from force-balance differential equations (Credit: Alan Zucconi)

Why Physics Engines Aren’t the Answer

One might ask: Why not simulate chains in real-time with physics engines? Rigid bodies linked via hinge joints can generate accurate catenaries. But as Zucconi emphasizes, this is prohibitively expensive for static background elements. A cathedral’s dangling cables shouldn’t consume CPU cycles better spent on gameplay. Worse, physics-based chains require settling time to stabilize—an inefficiency avoidable with precomputed catenaries.

Parametrizing the Impossible

To embed catenaries in games, developers need control over:

- Anchor points

P₁=(x₁,y₁)andP₂=(x₂,y₂) - Total chain length

L > distance(P₁,P₂)

Zucconi’s solution introduces auxiliary variables p and q:

p = \frac{\sqrt{L^2 - (y_2 - y_1)^2}}{x_2 - x_1}, \quad q = \frac{y_2 - y_1}{x_2 - x_1}

Then, a is found by numerically solving:

\sinh(p \cdot a) = q \cdot a

This is where theory meets friction: No closed-form solution exists. Game engines must deploy iterative methods (like Newton-Raphson) to approximate a efficiently.

Interactive catenary explorer demonstrating parameter effects (Credit: Alan Zucconi)

Interactive catenary explorer demonstrating parameter effects (Credit: Alan Zucconi)

Beyond Chains: The Architecture of Force

Catenaries aren’t just for wires—they’re engineering cornerstones. Flip one upside down, and you get an ideal arch that distributes load uniformly. St. Paul’s Cathedral’s dome relies on this principle, as highlighted in Zucconi’s reference to a Numberphile dissection. Games leveraging destructible environments could use this duality for realistic rubble.

The Path Forward

Zucconi’s upcoming Unity package (available via Patreon) tackles these hurdles with:

- 2D/3D catenary generators

- Support for rigged models (e.g., twisted cables)

- Uniform sampling for optimized mesh creation

As games strive for richer immersion, conquering catenaries moves from niche math to essential artistry—a reminder that sometimes, the most mundane details demand the most profound solutions.

Source: The Mathematics of Catenary by Alan Zucconi

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion