Windows XP emerged from Microsoft's chaotic quest to unify its consumer and professional operating systems, overcoming cancelled projects, design controversies, and post-9/11 rebranding to become one of history's most resilient OSes. Its legacy lies in setting new standards for stability, longevity, and user experience that reshaped developer expectations and defined an era.

In the late 1990s, Microsoft faced an existential paradox. Its ubiquitous products—Windows, Office, Internet Explorer—were so ingrained in daily life that any change sparked backlash. Yet, the foundation of this empire, MS-DOS and its consumer Windows derivatives, was a creaking relic. The company had long dreamed of ditching DOS for a modern kernel, a vision that nearly materialized with the ill-fated OS/2 partnership with IBM. When that collapsed in acrimony in 1990, Microsoft turned to DEC veteran David Cutler. His answer was Windows NT, a robust, 32-bit OS designed for stability and scalability, complete with virtual DOS machines (VDMs) for backward compatibility and personalities for UNIX and OS/2. NT was the future, but merging it with the consumer market proved treacherous.

The Ghosts of Neptune and Odyssey

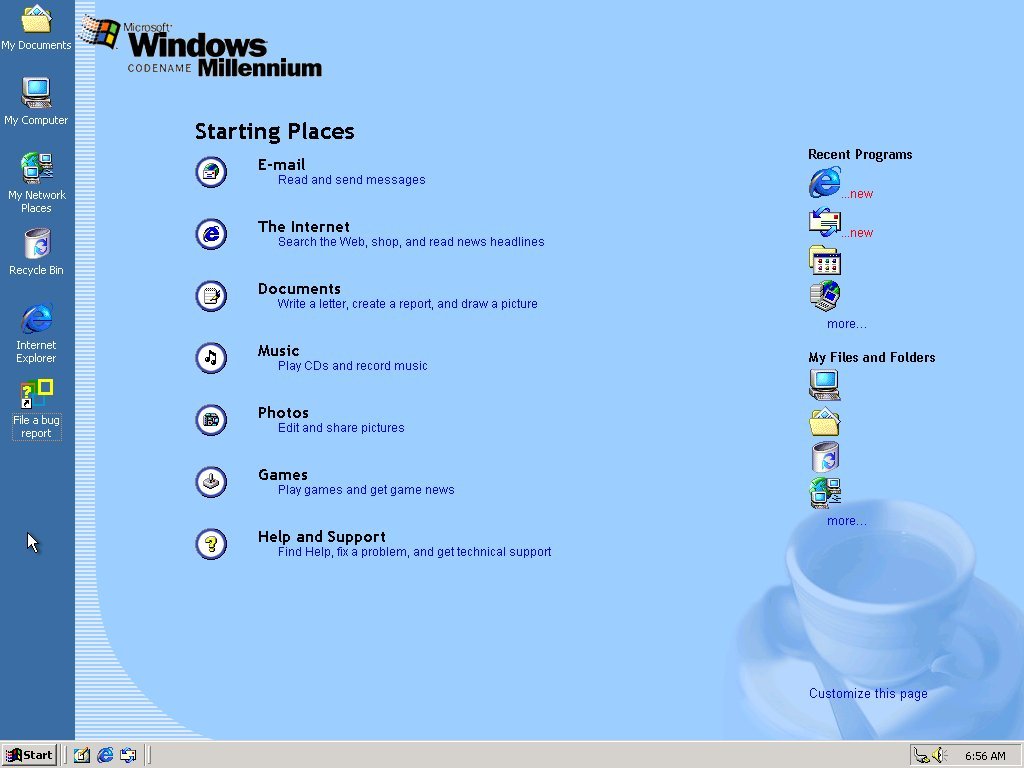

Microsoft's first attempt at a consumer NT was codenamed Neptune. Aimed at replacing Windows Me, it promised a revolutionary task-oriented interface built on the Mars framework, blending HTML/JS with Win32 for seamless experiences like auto-saving documents. Concepts revealed pages focused on single activities—email, media, documents—with a Start Screen that foreshadowed later Metro designs.  Neptune even introduced granular account types (Owner, Adult, Child, Guest), hinting at modern user management. Its sibling, Odyssey, targeted business users. But by late 1999, both projects were cancelled. As journalist Paul Thurrott noted at the time:

Neptune even introduced granular account types (Owner, Adult, Child, Guest), hinting at modern user management. Its sibling, Odyssey, targeted business users. But by late 1999, both projects were cancelled. As journalist Paul Thurrott noted at the time:

"Neptune became a black hole when all the features cut from Millennium were re-tagged as Neptune features. Since Neptune and Odyssey shared a codebase, combining them into a single project just made sense."

The result was Whistler, later known as Windows XP. Early builds (like 5.0.2211) retained remnants of Neptune—such as its login screen and Help Center—while stripping legacy cruft like OS/2 subsystem support and 80486 CPU compatibility. The cancellation wasn't failure; it was pragmatism. Neptune's ambition outpaced execution, but its DNA lived on in features like System Restore.

Design Alchemy and the Birth of Luna

With Whistler taking shape, Microsoft outsourced its soul to frog design, the firm behind icons like the Apple IIc and NeXT Cube. Tasked with refreshing Windows' look while preserving brand identity, frog crafted Luna—XP's signature theme. Its gradients, blues, and greens polarized users (dubbed "Fisher-Price" by critics) but delivered unprecedented visual cohesion.  Beta 2 (build 5.1.2428) in early 2001 unveiled Luna alongside critical under-the-hood advances: automated system recovery points pre-driver install and expanded compatibility modes for Windows 9x/2000 software. Technical compromises emerged too, like the reviled Windows Product Activation (WPA), which tied licenses to hardware hashes, frustrating upgraders.

Beta 2 (build 5.1.2428) in early 2001 unveiled Luna alongside critical under-the-hood advances: automated system recovery points pre-driver install and expanded compatibility modes for Windows 9x/2000 software. Technical compromises emerged too, like the reviled Windows Product Activation (WPA), which tied licenses to hardware hashes, frustrating upgraders.

The launch on October 25, 2001, was a masterclass in crisis adaptation. After 9/11 scrapped the "Prepare to Fly" campaign, Microsoft pivoted to "Yes You Can," soundtracked by Madonna's "Ray of Light." Ads featured the Bliss wallpaper—a Sonoma County hill captured by Charles O'Rear, bought by Bill Gates' Corbis for a fortune—symbolizing XP's promise of a fresh start. Underneath, XP was a powerhouse: DirectX 8.1 for gamers, Remote Desktop for IT, FireWire 800 support, and prefetching to accelerate app loads. It unified Microsoft's OS lines at last, with Home and Pro editions starting at $99.

The Engine That Wouldn't Quit

Initial reactions were mixed. Gamers clung to Windows 98 for DOS compatibility; privacy advocates recoiled at WPA. Yet XP's technical merits won out. Service Pack 1 (2002) added USB 2.0 and .NET support, while SP2 (2004) revolutionized security with Wi-Fi encryption and a centralized Security Center. Its resilience was legendary: XP outlived Vista and Windows 7, dominating global market share until 2012. Even after extended support ended in 2014, it persisted in embedded systems until 2019, powering everything from Pentium IIs to Core i7s with as little as 64MB RAM. At its peak, 17 million licenses sold in two months; today, it still runs on 0.5% of PCs.

XP succeeded by redefining expectations. It proved operating systems could be stable—no more constant reboots—and long-lived, easing the upgrade treadmill. Developers could rely on a consistent platform for over a decade, fostering an ecosystem where applications thrived across hardware generations, from spinning disks to early SSDs. Its decline came not from failure, but from evolving tech demands that outpaced its core. For engineers, XP remains a benchmark: a testament to how unifying vision, thoughtful design, and relentless iteration can turn chaos into an enduring legacy that shaped computing's trajectory.

Source: Abort Retry Fail, 'The History of Windows XP' (abortretry.fail)

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion