A new approach to documentation translation treats translations as versioned software assets rather than static outputs, enabling better synchronization and maintenance for large, fast-moving documentation repositories.

When translations quietly become a liability In most documentation projects, translations are treated as finished outputs. Once a file is translated, it is assumed to remain valid until someone explicitly notices a problem. But documentation rarely stands still. Text changes. Code examples evolve. Screenshots are replaced. Notebooks are updated to reflect new behavior.

The problem is that these changes are often invisible in translated content. A translation may still read fluently, while the information it contains is already out of date. At that point, the issue is no longer about translation quality. It becomes a maintenance problem.

Reframing the question Most translation workflows implicitly ask: Is this translation correct? In practice, maintainers struggle with a different question: Is this translation still synchronized with the current source?

This distinction matters. A translation can be correct and still be out of sync. Once we acknowledged this, it became clear that treating translations as static content was no longer sufficient.

The design decision: translations as versioned assets Starting with Co-op Translator 0.16.2, we made a deliberate design decision: Translations are treated as versioned software assets. This applies not only to Markdown files, but also to images, notebooks, and any other translated artifacts.

Translated content is not just text. It is an artifact generated from a specific version of a source. To make this abstraction operational rather than theoretical, we did not invent a new mechanism. Instead, we looked to systems that already solve a similar problem: pip, poetry, and npm. These tools are designed to track artifacts as their sources evolve. We applied the same thinking to translated content.

Closer to dependency management than translation jobs The closest analogy is software dependency management. When a dependency becomes outdated: it is not suddenly "wrong," it is simply no longer aligned with the current version. Translations behave the same way. When the source document changes: the translated file does not immediately become incorrect, it becomes out of sync with its source version.

This framing shifts the problem away from translation output and toward state and synchronization.

Why file-level versioning matters Many translation systems operate at the string or segment level. That model works well for UI text and relatively stable resources. Documentation is different. A Markdown file is an artifact. A screenshot is an artifact. A notebook is an artifact. They are consumed as units, not as isolated strings.

Managing translation state at the file level allows maintainers to reason about translations using the same mental model they already apply to other repository assets.

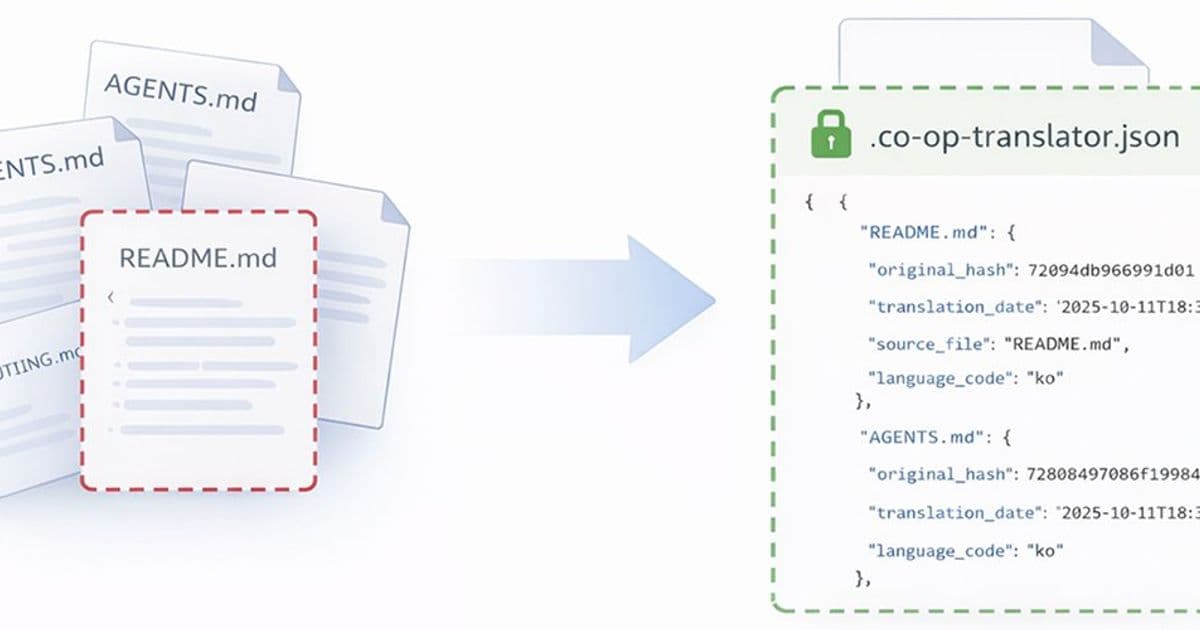

What changed in practice From embedded markers to explicit state Previously, translation metadata lived inside translated files as embedded comments or markers. This approach had clear limitations: translation state was fragmented, difficult to inspect globally, and easy to miss as repositories grew.

We moved to language-scoped JSON state files that explicitly track: the source version, the translated artifact, and its synchronization status. Translation state is no longer hidden inside content. It is a first-class, inspectable part of the repository.

Extending the model to images and notebooks The same model now applies consistently to: translated images, localized notebooks, and other non-text artifacts. If an image changes in the source language, the translated image becomes out of sync. If a notebook is updated, its translated versions are evaluated against the new source version. The format does not matter. The lifecycle does.

Once translations are treated as versioned assets, the system remains consistent across all content types.

What this enables This design enables:

- Explicit drift detection See which translations are out of sync without guessing.

- Consistent maintenance signals Text, images, and notebooks follow the same rules.

- Clear responsibility boundaries The system reports state. Humans decide action.

- Scalability for fast-moving repositories Translation maintenance becomes observable, not reactive.

In large documentation sets, this difference determines whether translation maintenance is sustainable at all.

What this is not This system does not: judge translation quality, determine semantic correctness, or auto-approve content. It answers one question only: Is this translated artifact synchronized with its source version?

Who this is for This approach is designed for teams that: maintain multilingual documentation, update content frequently, and need confidence in what is actually up to date.

When documentation evolves faster than translations, treating translations as versioned assets becomes a necessity, not an optimization.

Closing thought Once translations are modeled as software assets, long-standing ambiguities disappear. State becomes visible. Maintenance becomes manageable. And translations fit naturally into existing software workflows.

At that point, the question is no longer whether translation drift exists, but: Can you see it?

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion