Kubernetes was built for flexibility, not efficiency, leaving teams to overprovision and underutilize resources. This article traces the root causes—from static resource requests to flawed autoscalers—and shows how modern tools like Karpenter and predictive scheduling can turn the tide.

Why Kubernetes Is Eating Your Cloud Dollars and How to Stop It

Kubernetes has become the de‑facto platform for container orchestration, but its very design makes it a cost‑draining monster. Despite the promise of elastic scaling, most clusters run at a fraction of their capacity, with autoscalers adding nodes that sit idle and VPA recommendations lagging behind real demand. The result is a steady climb in cloud spend that many teams only notice after the fact.

The Efficiency Gap: From Borg to Kubernetes

Google’s Borg was a highly tuned, predictive scheduler that balanced CPU, memory, and I/O across thousands of nodes. When Borg’s core concepts were open‑sourced as Kubernetes, the optimization logic was largely stripped away, leaving a flexible API that excels at developer experience but is blind to usage patterns. As a consequence, Kubernetes clusters drift toward inefficiency unless teams actively correct for it.

The CNCF report shows that almost 50 % of users saw spending rise after adopting Kubernetes—yet the platform offers no native mechanism to prevent waste.

Static Requests vs. Dynamic Workloads

Kubernetes allocates resources statically: every pod declares a CPU request and a memory limit, and the scheduler treats those numbers as immutable. This forces developers to plan for peak loads, leading to overprovisioning. Common pitfalls include:

- JVM services with fixed Xms/Xmx settings that ignore off‑heap memory, inflating requests.

- Thread‑pool over‑sizing that masks true CPU usage.

- LLM workloads that reserve large GPU instances during model loading but leave them idle afterward.

Right‑sizing requires tuning container‑aware settings such as UseContainerSupport, MaxRAMPercentage, and real RSS measurements.

The Autoscaler Conundrum

Kubernetes ships two autoscalers: the Horizontal Pod Autoscaler (HPA) and the Vertical Pod Autoscaler (VPA). Each has a narrow focus but can clash when they target the same metrics.

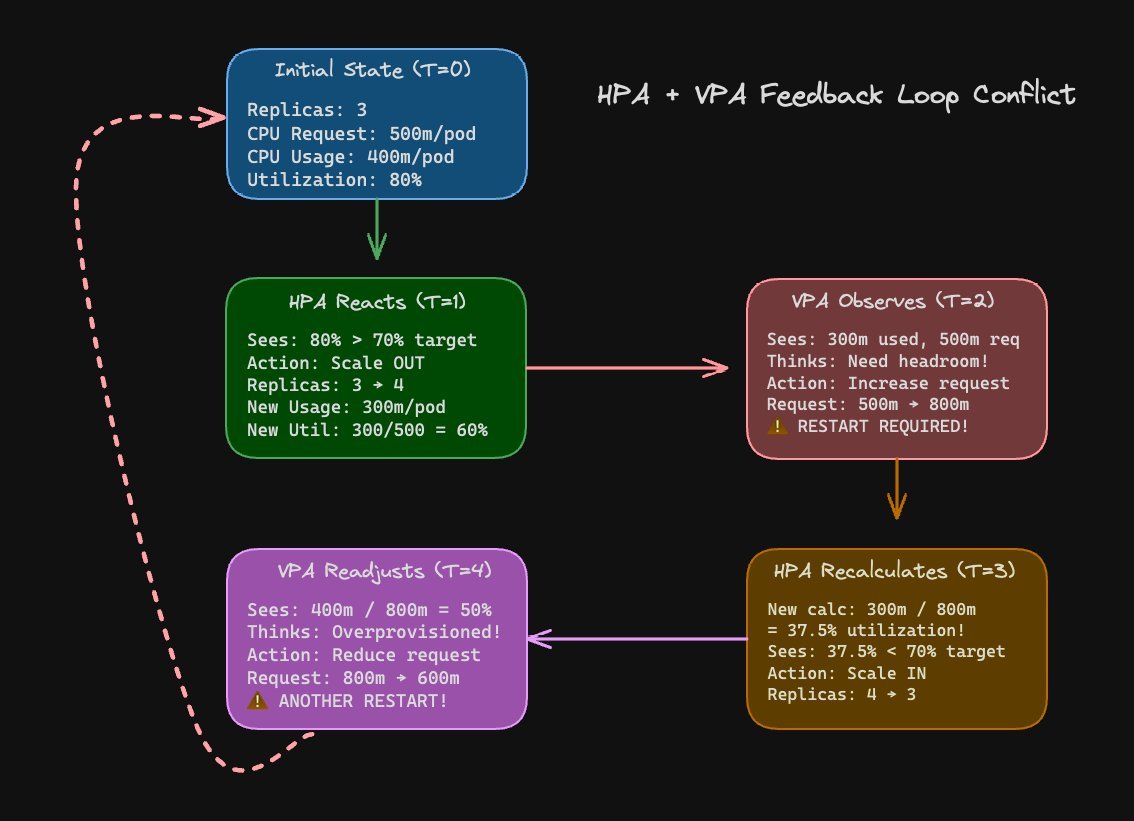

Figure 2: HPA + VPA feedback loop

When the HPA scales out based on CPU usage while the VPA adjusts pod requests, the HPA’s utilization calculation flips, triggering another scale‑out or scale‑in. This oscillation can cause pods to restart repeatedly, wasting compute and increasing latency.

Best practice is to base HPA triggers on business‑level metrics (queue depth, latency, QPS) rather than raw CPU/memory, and to keep VPA in a mode that avoids frequent restarts.

Bin Packing: The Core of the Problem

The scheduler’s default LeastAllocated strategy spreads pods evenly across nodes, prioritizing resilience over packing efficiency. This leads to fragmented resources where CPU‑heavy and memory‑heavy pods coexist on the same node, leaving unusable gaps.

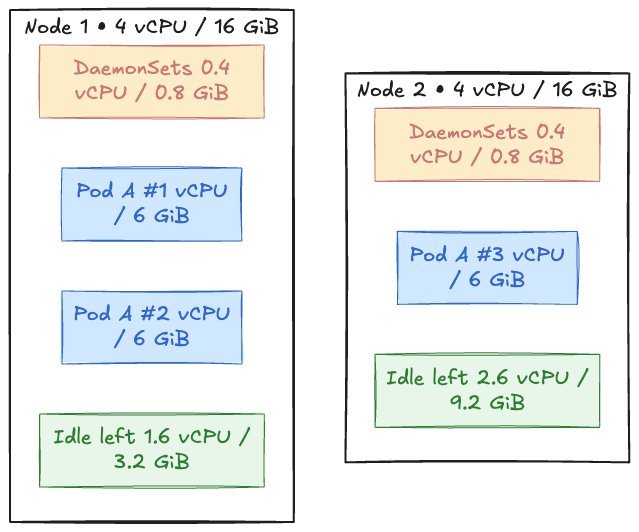

Figure 3: Example nodes for bin packing

Consider a 4 vCPU / 16 GiB node with a DaemonSet consuming 0.4 vCPU / 0.8 GiB. Two web pods (1 vCPU / 6 GiB each) fit, but a third pod is pending because of insufficient memory. The cluster autoscaler then adds a new node, even though the first node has 45 % idle CPU.

This classic bin packing problem is multi‑dimensional: solving for CPU alone leaves memory holes, and vice versa.

Existing Tools and Their Limits

- Cluster Autoscaler watches for pending pods and resizes node pools, but it relies on pre‑defined instance families and cannot predict future needs.

- Karpenter reacts to pending pods by consolidating or replacing nodes, yet its simple matching algorithm can still spin up new nodes when an existing one is underutilized.

Both tools improve over the bare‑bones autoscaler but fall short of a global optimizer that can right‑size workloads, predict demand, and pack pods efficiently.

Toward a Continuous Optimization Loop

The real solution lies in combining three capabilities that Borg mastered but Kubernetes omitted:

- Predictive autoscaling that forecasts demand based on historical patterns.

- Workload‑aware scheduling that packs pods by actual resource usage, not just requests.

- Live monitoring that feeds real‑time utilization back into the scheduler and autoscalers.

Until these features become native, teams must stitch together third‑party tools or build custom solutions. One emerging approach is live rightsizing, where the system continuously adjusts pod requests and node types without restarts, achieving higher node utilization and lower costs.

The Bottom Line

Kubernetes’ architecture was never intended to be a global optimizer; it was designed for flexibility and developer convenience. The cost implications of overprovisioning, misconfigured autoscalers, and poor bin packing are real and widespread. By adopting smarter scheduling, predictive scaling, and real‑time rightsizing, organizations can reclaim wasted dollars and run workloads more efficiently.

Source: https://www.devzero.io/blog/whats-wrong-with-kubernetes-today

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion