A six-figure property fraud targeting vacant land in Wilton, CT reveals how scammers exploit digital real estate transactions and the challenges of stopping them.

In March 2024, I received an email from a real estate attorney in Wilton, Connecticut that started with a simple question: "Are you the Fred Benenson who co-owns property in town with an Ed Benenson?"

It wasn't.

Neither my brother Alexander nor I had spoken to anyone about selling the small parcel of vacant land we purchased at 221 Cannon Road in 2015. We've owned it for over a decade and have never listed it for sale. Yet someone had been impersonating us, providing accurate property details, and had already secured a full-price cash offer.

The scammer had contacted a realtor through Zillow, claiming to be me. They'd had a phone conversation—the realtor noted the person had a "middle European" accent—and provided what seemed like legitimate information: the exact acreage, our supposed email addresses ([email protected] and [email protected]), and even a phone number (516) 828-0305.

The property had been listed on dozens of real estate websites for days before anyone caught it. A builder had already submitted a full-price cash offer. The scammer had even e-signed a purchase agreement.

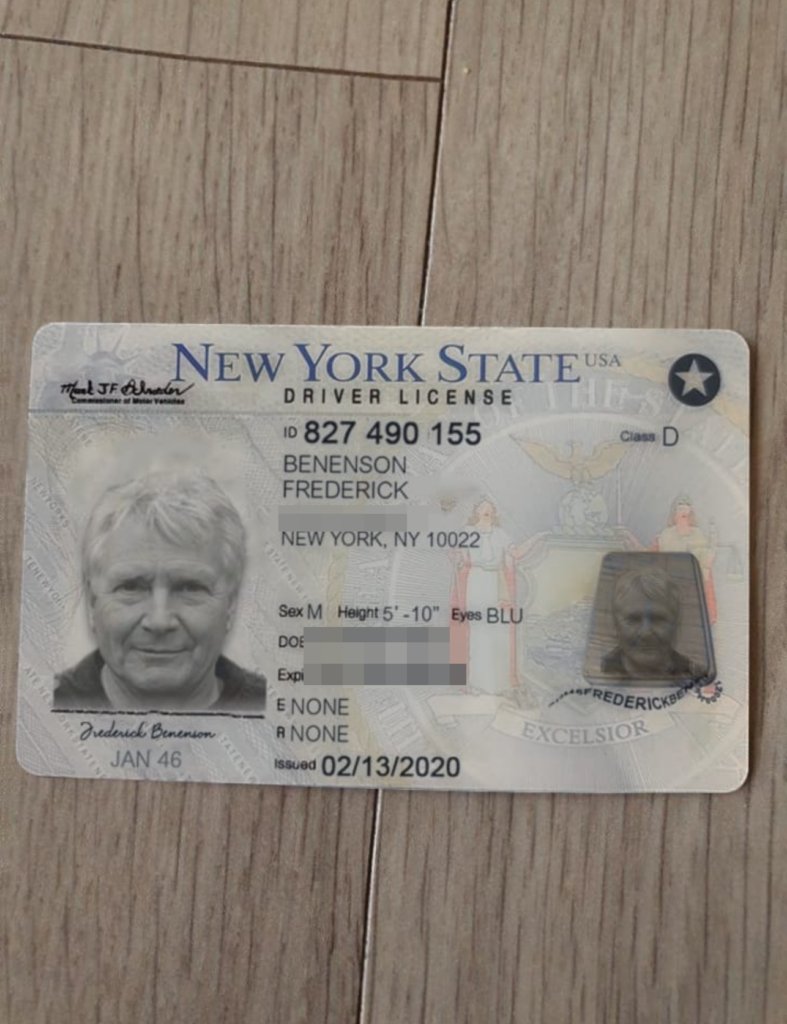

When the attorney requested identification before closing, the impostor provided a New York State driver's license. It had my father's name (which I share with him) and his correct date of birth and home address. But the photo was of a complete stranger.

I have no idea who that guy is on the license, but it's definitely not my Dad. The license wouldn't fool anyone who knew my father, but it didn't need to—in a transaction conducted entirely by email and text message, with a closing that the scammer would never actually attend, the ID just needed to look plausible enough to keep things moving forward.

How It Was Caught The attorney deserves most of the credit here. He told me this was the second time in nine months he'd encountered this exact scheme on vacant land in Wilton—his policy is that he won't represent owners of vacant land without independently verifying ownership. That's what led him to track me down, and that's what stopped the sale.

The realtor was an innocent victim in this too. She'd done her job by walking the property, pulling comps, etc., all in good faith. When I initially suggested (perhaps unfairly) that this felt like lead generation, the attorney took me aside and vouched for her. I'm glad I listened to him!

I apologized to her, and she graciously forwarded me all of her text message exchanges with the scammer. Reading through them was fascinating. The impostor was responsive, polite, and generally knew the right things to say. But there were tells: slightly awkward phrasing ("Hi good morning"), declining a for-sale sign ("No I don't think that will be necessary"), and a general reluctance to engage in any way that might require showing up in person.

Going to the FBI After gathering everything I could—the fake ID, the realtor's text messages, the scammer's email addresses and phone number, and the attorney's notes from a prior similar case—I contacted the FBI field office in Connecticut. They directed me to "walk it in" to the office in New York City.

The experience was, frankly, underwhelming. The FBI wouldn't let me submit any of our documentation. Instead, they required me to write out the entire complaint by hand on a single piece of paper and hand it to the guard. He made some calls while I waited, and by the end he seemed at least somewhat interested. He gave me the standard line: 2-3 weeks if I hear from anyone.

I never heard from anyone.

The attorney, meanwhile, checked with his title company about recording an affidavit on the land records—something that would alert any future buyer or title searcher that the property had been targeted by fraud, and providing our verified contact information.

It's Happening Again (February 2026) I thought this was behind us. Then, this past week, nearly two years later, I was contacted by two more real estate agents, both reaching out to warn me that someone was once again trying to sell 221 Cannon Road.

The first was an agent in Wilton who reached out via Instagram DM, of all places—it was the only way he could find to contact me. He explained that his team had received an inquiry to list 221 Cannon Road and had sent paperwork to "Fred and Alex" the night before to sign. But he'd done something smart: he'd noticed he had a mutual friend with my brother, and when he asked him about the situation, he flagged that the conversation with "Alex" didn't sound right.

"I had a really bad feeling it wasn't," he told me.

The second agent, a woman at Berkshire Hathaway, sent a carefully worded email explaining that she'd been contacted by someone claiming to have authority to sell our property, but that "several standard verification steps raised concerns" and she chose not to proceed. She reached out purely as a courtesy to let us know.

Which is about when I decided I should write something about this. Not only because it's a fascinating scam that seems to be getting more common, but because I figured this post might show up for the next broker who might be doing research on the address.

Vacant Land Fraud This type of scam targets a very specific vulnerability: vacant land has no occupants to notice a for-sale sign, no neighbors who'd immediately recognize something is wrong, and closings often happen remotely. Here's how it works:

The scammer identifies vacant land through public records or Zillow. They look for parcels that are owned free and clear (no mortgage), haven't changed hands recently, and are in desirable areas.

They contact a real estate agent through a platform like Zillow, posing as the owner. They know the property details because that information is publicly available.

They communicate primarily through text and email, avoiding in-person meetings.

They provide fake identification if asked.

They agree to whatever price the agent suggests (because they don't actually own the property, any sale is pure profit).

They push for a quick closing and attempt to direct proceeds to an account they control.

If questioned, they disappear.

The scammer who targeted us in 2024 simply stopped responding once the attorney asked for an in-person closing. If they get farther they'll pocket the earnest money deposit which would have been significant in my case.

A similar scheme in nearby Fairfield wasn't caught in time: someone had a $1.5 million home built on land they didn't own without the actual owners knowing.

What You Can Do If you own vacant land there are a couple of things you can do, but the most effective one is probably to register the address with a Fraud / No-Authority notice. This involves calling the County Recorder / Register of Deeds and ask how to record one of these (names vary by state):

• Owner Affidavit • Affidavit of Fact • Notice of Non-Authority to Convey • Fraud Alert / Title Alert Notice • Statement of Ownership / Anti-Fraud Notice

You could also setup up Google Alerts for your address and you'll be notified if it appears online.

Finally, and this certainly isn't for everyone, you can make yourself easily findable online. One reason the attorney was able to verify ownership quickly in 2024 was that it's fairly easy to google me. If you own property, make sure there's some way for a diligent attorney or agent to reach the real you.

The Property Is Not For Sale In case it isn't clear, 221 Cannon Road is not for sale. It has never been for sale. If you are a real estate professional who has been contacted about listing or purchasing this property, please reach out to me directly.

This isn't just my problem—it's a growing issue in the real estate industry. As transactions move increasingly online, the opportunities for this type of fraud multiply. The fact that it's happened to me twice in two years suggests this scam is becoming more common, not less.

So consider this both a warning and a resource. If you're a real estate professional who encounters this scam, maybe this post will help you verify ownership before wasting time on a fraudulent listing. And if you're a property owner, take steps now to protect yourself before someone tries to sell your land out from under you.

Because in the digital age, your property isn't just vulnerable to physical theft—it's vulnerable to someone with a fake ID, a convincing email address, and enough patience to play the long game.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion