Microsoft's 30-year journey with desktop widgets reveals a repeating cycle of innovation and failure, where each iteration's fatal flaw shaped the constraints developers face today.

Microsoft has attempted to solve the same UX challenge since 1997: delivering live information without requiring app launches. Over six distinct iterations spanning nearly three decades, each widget implementation died from different fundamental weaknesses—performance, screen space, security, engagement, privacy—only to resurface in a more constrained form. This pattern reveals why today's widget architecture carries specific technical limitations that aren't arbitrary but represent accumulated solutions to past disasters.

The Push Era (1997–2001): When Performance Killed Ambition

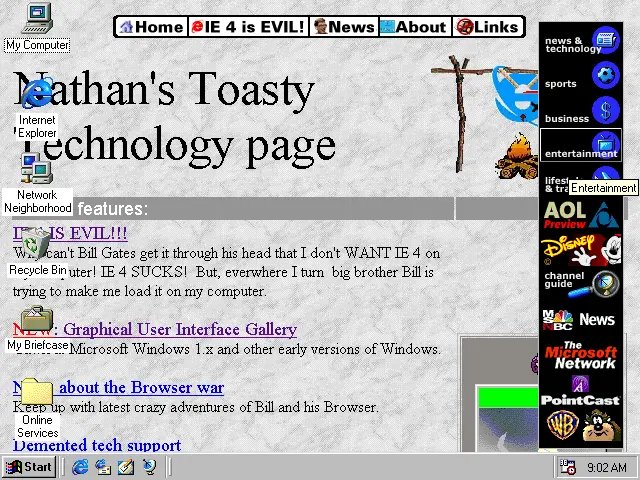

Internet Explorer 4.0 introduced Active Desktop, embedding Trident's rendering engine directly into explorer.exe to transform wallpapers into live HTML surfaces. The Active Channel Bar docked to the screen's right edge delivered content through Channel Definition Format (CDF), pushing updates like CNN headlines overnight for offline access.  shows HTML rendering directly on the desktop alongside branded channel buttons.

shows HTML rendering directly on the desktop alongside branded channel buttons.

The concept collapsed under hardware limitations: Pentium I/II processors with 16–32MB RAM couldn't handle constant HTML rendering. Crashes in Active Desktop took down explorer.exe entirely, while background syncs crippled disk I/O. This established the first rule of widgets: ambient information cannot degrade system performance.

The Glass Era (2007–2009): The Cost of Fixed Screen Real Estate

After a dormant period during Windows XP, widgets returned in Vista's translucent sidebar—a rigid pane occupying the right screen edge.  shows the Aero Glass design with CPU meters mimicking car dials and clocks with sweeping second hands. Though developers created thousands of .gadget files (renamed ZIPs containing HTML/CSS/JScript), the fixed 150-pixel width consumed over 10% of 1280x1024 displays. The sidebar.exe process also leaked memory, consuming 50-100MB on 1GB RAM systems. Containment through docking failed when screen space became sacred.

shows the Aero Glass design with CPU meters mimicking car dials and clocks with sweeping second hands. Though developers created thousands of .gadget files (renamed ZIPs containing HTML/CSS/JScript), the fixed 150-pixel width consumed over 10% of 1280x1024 displays. The sidebar.exe process also leaked memory, consuming 50-100MB on 1GB RAM systems. Containment through docking failed when screen space became sacred.

The Free Era (2009–2012): Security Explosions from Excessive Freedom

Windows 7 removed the sidebar, letting gadgets float freely and snap to screen edges. Third-party widgets flourished—from Winamp controllers to CPU monitors ( ). This golden age ended at Black Hat 2012 when researchers demonstrated how weather gadgets could be hijacked: attackers injected malicious JavaScript into XML data streams, exploiting ActiveX controls to execute system commands via the trusted sidebar.exe process. Microsoft responded by permanently disabling the feature, establishing that freedom without sandboxing invites catastrophe. This failure directly inspired today's declarative Adaptive Cards architecture.

). This golden age ended at Black Hat 2012 when researchers demonstrated how weather gadgets could be hijacked: attackers injected malicious JavaScript into XML data streams, exploiting ActiveX controls to execute system commands via the trusted sidebar.exe process. Microsoft responded by permanently disabling the feature, establishing that freedom without sandboxing invites catastrophe. This failure directly inspired today's declarative Adaptive Cards architecture.

The Metro Era (2012–2021): When Read-Only Tiles Killed Engagement Windows 8 locked widgets into full-screen Live Tiles, updating via XML payloads without background processes. Though battery-efficient and secure (executing no code), the experience required disruptive context switches to access information. Tiles were also read-only—unlike Windows 7's interactive gadgets—forcing app launches for simple actions. Developers avoided the costly WNS backend infrastructure, resulting in neglected, static tiles. Containment through isolation sacrificed utility.

The Interlude (2015–2021): Privacy and Disruption Pitfalls Cortana Cards (2015-2020) delivered powerful features like flight tracking and calendar insights but required deep email access, triggering privacy concerns. News and Interests (2021) used hover-activated popups that accidentally triggered during cursor movement toward the system tray. Both attempts proved users reject invasive data collection and unintentional disruptions.

The Board Era (2021–Present): Evolution Through Regulation and Architecture Windows 11's Widget Board initially used WebView2 rendering, drawing criticism for memory usage and forced MSN content. The EU's Digital Markets Act catalyzed change: Microsoft decoupled the news feed into a replaceable component and rebuilt the rendering engine with native WinUI 3. Adaptive Cards now map directly to lightweight XAML controls, slashing memory use while maintaining security through declarative JSON. Interactive widgets—like Spotify controls and messaging replies—operate within strict sandboxes. Lock Screen widgets (2026) finally realize the 1997 'glance and go' vision with hardware capable of supporting it.

The current platform encodes every past failure: declarative JSON prevents code execution, WinUI 3 ensures performance, overlay layouts preserve screen space, interactivity boosts engagement, and opt-in data flows protect privacy. Yet challenges remain—API constraints, discoverability issues, and tensions between utility and monetization in the Discover feed. These limitations aren't arbitrary; they're the accumulated wisdom of three decades of building and breaking widget ecosystems.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion