Why separating meaning from presentation is the key to future-proofing your content for omnichannel delivery.

Do you remember when having a great website was enough? Those were simpler times. Today, your content needs to live in Google knowledge panels, answer questions through Siri, appear in mobile apps, and feed chatbots. This reality has pushed organizations toward omnichannel content strategies, but the technical foundation for these strategies often trips up even experienced teams. The culprit is a subtle but critical confusion: treating your content model like a design system.

I learned this lesson while leading a CMS implementation for a Fortune 500 company. The client wanted the holy grail of modern content strategy: create once, publish everywhere. They envisioned their content flowing seamlessly into voice interfaces, search snippets, and future platforms we haven't even imagined yet. The content model—the formal definition of content types, their attributes, and how they relate—would be the backbone of this strategy. But as we built it, I watched our team repeatedly fall into the same trap: we were designing for the web we knew, not the content ecosystem we needed.

The problem wasn't lack of skill or good intentions. It was that our brains had been trained by years of design-system thinking. We kept reaching for familiar patterns like "teasers," "cards," and "media blocks"—components that made perfect sense for building web layouts but created content that was essentially blind to the world beyond our current website.

The Semantic Imperative

A semantic content model names things for what they are, not how they look. This distinction seems trivial until you try to reuse content across channels.

Consider the difference. A non-semantic approach creates types like "hero banner" or "feature card." These names describe visual containers. They tell you where content goes on a page but nothing about what the content means. When you need that same content in a voice assistant or a Google snippet, you're stuck. The system has no way to understand that your "hero banner" contains a product name, or that your "feature card" holds a customer testimonial.

A semantic approach instead creates types like Product, Service, or Testimonial. These names carry meaning that any system can interpret. A product is still a product whether it appears as a web page section, a search result, or a voice response.

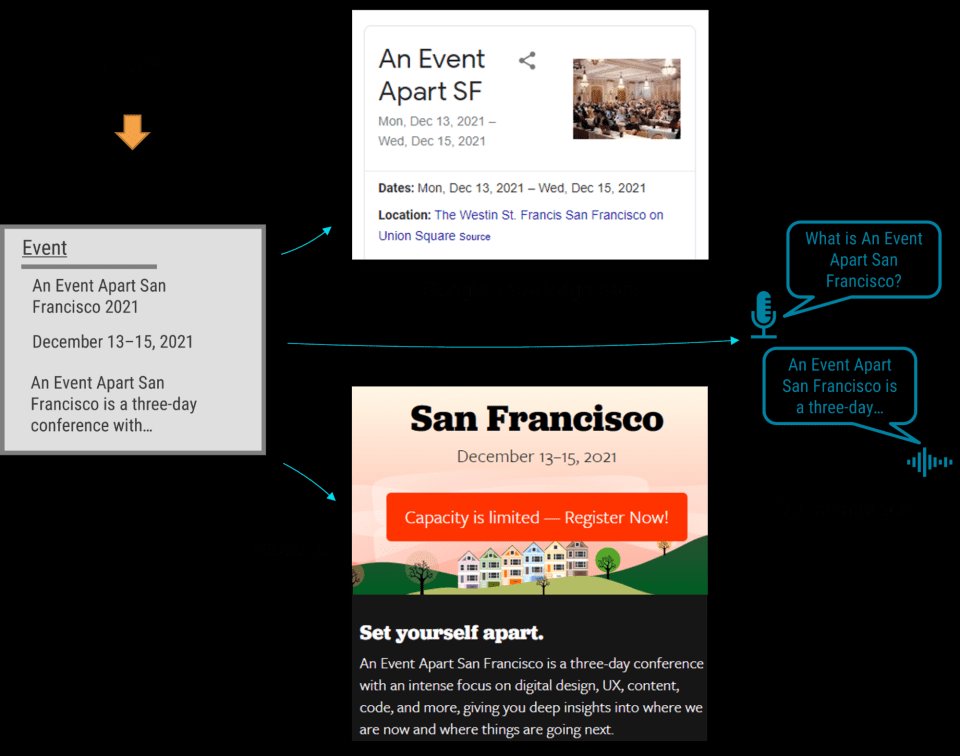

The benefits cascade. First, semantic models decouple content from presentation entirely. Your marketing team can redesign the website five times without touching the content structure. Second, they unlock search engine advantages. Schema.org provides a vocabulary of semantic types that Google, Bing, and other search engines understand natively. When your content model aligns with these standards, you get rich snippets, knowledge panels, and better discoverability without extra work.

Most importantly, semantic models enable true omnichannel delivery. Take a simple FAQ. In a semantic model, each question-answer pair stays together as a structured unit. That same content can render on a web page, feed a chatbot, power a voice interface, or appear in a mobile app. Without semantics, you're manually reformatting content for each channel—a maintenance nightmare.

The Glue That Binds

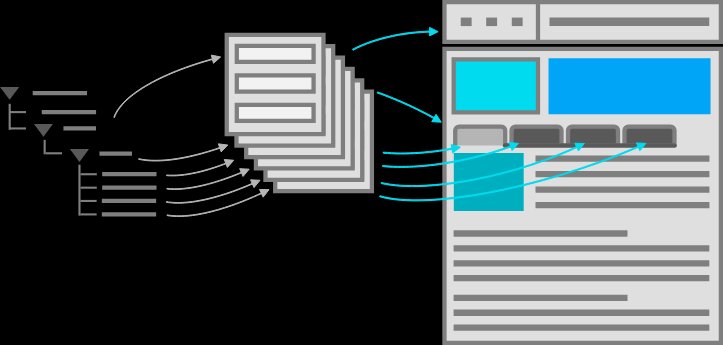

The second principle is equally vital: content models must connect what belongs together. This sounds obvious, but design-system thinking actively works against it.

When designers present a complex page layout—say, a software product page with multiple tabs for overview, specs, resources, and pricing—the intuitive move is to mirror that structure in the content model. You might create a "tab section" content type, thinking this gives authors flexibility to add and reorder tabs.

This feels logical and matches the visual design. It's also wrong.

Here's what happens: you've now fragmented related information across disconnected chunks. The product's specifications live in one "tab section" instance, its resources in another. A voice interface trying to answer "what are the specs for Product X?" has no way to know which tab section contains specs versus resources. It would need to count tabs or parse visual layout cues—essentially reverse-engineering your design system.

Worse, when the design inevitably changes (tabs become accordions, or the page restructures completely), you face a content migration nightmare. Every piece of content is tied to a presentation concept that no longer exists.

The semantic approach keeps product information together. A Product type contains attributes like name, description, specifications, resources, and pricing. These are meaningful relationships, not layout positions. The presentation layer decides whether to show them as tabs, accordions, or separate pages. The content model stays stable.

Breaking the Design-Model Habit

The hardest part isn't understanding these principles—it's resisting the gravitational pull of design-system thinking. Visual design feels concrete and immediate. Semantic modeling feels abstract and theoretical. When deadlines loom, it's tempting to just mirror the mockups.

Several strategies help:

Start with meaning, not layout. Before any design exists, interview stakeholders about what information needs to be communicated and why. What questions must this content answer? What decisions will it inform? Build the content model from these functional requirements.

Use Schema.org as a guide. This community-maintained vocabulary already defines semantic types for most common content. Aligning with it gives you a head start on search optimization and ensures your model speaks a language other systems understand.

Involve the entire team early. Designers, developers, and content authors all need to understand why semantic modeling matters. Show them how a "teaser" type creates lock-in while a "testimonial" type creates flexibility. Make the cost of presentation-coupled content visible.

Question visual patterns. When a design calls for tabs, ask: what information are we organizing? Could that same information appear differently elsewhere? If the answer is yes, the content model shouldn't know about tabs.

The Long View

Even if omnichannel delivery isn't on your immediate roadmap, semantic modeling pays dividends. Search engines reward structured data. Future redesigns become simpler when content isn't entangled with old layouts. Most importantly, you treat content as a strategic asset rather than a design artifact.

The temptation to conflate content models with design systems will never disappear. It's rooted in legitimate desires for consistency, efficiency, and tangible progress. But resisting that temptation is what separates content that lasts from content that needs rebuilding every time your digital strategy evolves.

Your content deserves to be understood by machines and humans alike, across any channel that emerges. That starts with modeling it for what it means, not where it goes.

Comments

Please log in or register to join the discussion